and how they helped evolve our ‘health services’

From Leper houses that ‘hid’ victims – Almshouses – Pest House – Quarantine ships – Infirmaries – to St Williams that was able to treat patients with a contagious disease. (You may also like to view my subsequent blog about Medway’s Anti-vaccinators in the 19th century.)

No one today has experienced or lived through an epidemic of the magnitude of COVID-19. But this experience was not usual for our predecessors in Medway. I’ve tried to take a look at what they faced and how they learnt and dealt with epidemics that killed hundreds maybe thousands, across Medway, Kent.

Probably from before Roman times, Rochester, then Chatham, provided ideal conditions for infectious diseases to be brought into the area, and for them to take hold. This is an account of some of those epidemics and our response – which are not a lot different to those being taken in 2020 – perhaps making the case for ‘learning from history’ as opposed to just ‘learning history’?

The following is likely to be refined when ‘lockdown’ is released. Reference sources are included as it’s possible this will be a topic for school projects / dissertations in the future. Green text is observational, Orange text are sources, Purple is information provided by my blog readers.

Introduction

The bridge funnelled people into and through Rochester. People brought trade, and a trading community soon built up around the bridge. The river Medway brought commercial shipping, the Navy and the military to the towns – each providing a route from distant places into the Towns. As the towns grew haphazardly with no sanitation, diseases found conditions here very much to their liking.

Whilst ‘rock-pooling through history’ for accounts of previous epidemics that Medway had survived, it became clear that the steps being to constrain the spread of COVID-19 are little different to those practiced and refined by our predecessors; avoiding contacts / social-distancing, isolation / self-isolation, repurposing of facilities, rapid creation of extra capacity, and ‘special’ mortuary arrangements.

Over time as hospital facilities were developed we were encouraged to take more responsibly for ourselves by taking up vaccinations, and by complying with regulations aimed at constraining the spread of disease, and thereby protect the capacity of hospitals to treat the sick – and all before the NHS.

What was also clear is that major epidemics disrupted the established social and economic order, and may have driven stepped-changes in our health provision. It will be interesting to see what comes out of this epidemic – economically and socially. It has already served as a reminder of the frailty of the human condition, and that of our health & social care services which, of recent, have been more closely ‘costed’ than ‘valued’.

All events have a ‘cause’ and ‘consequence’. The following – largely chronological – endeavours to follow particular epidemics that occurred in Medway in order to find local and national connections and consequences.

+++++++

11th Century – exclusion rather than isolation?

Leprosy – it is clear that leprosy was established in Britain before the Crusades (1096) – that some blame for the disease reaching our shores. The ‘hospitals’ provided for lepers were probably less about isolating a contagion, and more about providing for those unable to support themselves because of their illness.

Gundulph, the Bishop of Rochester, in 1078 established a house for the reception leprous and other poor persons native to Kent. It was probably on the site near the chapel in Gundulph Road. When built its location would have been on the edge of the City and on a main route – the Roman London road. The actual design is not known but based on other sites it could have consisted of a group of small cottages close to the chapel, or it may have been no more than an annex to the chapel.

Gilbert de Glanvill, Bishop of Rochester, in 1193, founded a hospital in Strood/Newark Hospital. The hospital was for the receiving and cherishing of the poor, weak, infirm and impotent and travellers from distant places. This was in addition to the Hospital of Whyte Ditch which stood on the hill than descends into Strood, and previously known as ‘Spittal Hill’, that provided for lepers.

In 1316 Simond Potyn endowed a hospital for people with leprosy or “other pouer mendicants”. It was called “The spittle of St. Katherine of Rochester in the suburbs of Eastgate”. It was located at what is now the bottom of Star Hill, Rochester. The hospital moved to new premises at the top of Star Hill in 1805.

Leprosy significantly declined during the 16th century. This may have been due to resistance developing in the population as those who were genetically susceptible to the disease lived in leper communities – probably with limited opportunities to have offspring.

14th Century – The Plague leads to major disruption of the established social and economic order.

Details of the 1349 outbreak of the Plague (The Great Mortality) at Rochester was recorded by William de la Dene from Rochester Cathedral Priory:

“A great mortality destroyed more than a third of the men, women and children. As a result, there was such a shortage of servants, craftsmen, and workmen, and of agricultural workers and labourers, that a great many lords and people, although well-endowed with goods and possessions, were yet without service and attendance.

Alas, this mortality devoured such a multitude of both sexes that no one could be found to carry the bodies of the dead to burial, but men and women carried the bodies of their own little ones to church on their shoulders and threw them into mass graves, from which arose such a stink that it was barely possible for anyone to go past a churchyard.” {Population of Rochester in 1377 was 1070. (Click for – History of Epidemics in Britain, Charles Creighton. 1891).}

Rochester Castle besieged and bridge damaged

As described by William la Dene the Plague had a significant impact on the social order – particularly in Kent and Essex. The extensive loss of lives gave the working classes more economic clout. The aristocratic class attempted to curtail this and a chain of events followed that led to the Peasants’ Revolt in 1381.

Rochester saw a lot of activity associated with the Peasants’ Revolt. It was led by Wat Tyler from Kent, and involved the last besieging of Rochester Castle to secure the release of one the leaders of the revolt who was being held in prison there. The poor condition of the wooden bridge at Rochester in 1382 was attributed to the “unwonted traffic caused by the Peasants’ Revolt”. (Rochester Bridge 1387-1856. Janet Becker. 1930.)

Although the revolt was quashed the Plague helped accelerate the breakdown of the feudal system introduced by William the Conquer.

17th Century – distancing from infected households practiced, isolation houses introduced.

We are able to discover something of the impact of the Plague on Rochester through the accounts of the Richard Watts charity (Unpublished – but read by the author). In his Will of 1579 Richard Watts, a Rochester businessman, left money and land to provide accommodation for six poor travellers and work for the poor.

The charity’s accounts show that in 1610 many payments were made in respect of what were termed ‘extraordinary charges’ for the “relief of diverse poor petiole of the city who were in extreme poverty and sickness”. Payments were also made to widows for the care of children, and 10s 6d was paid for burying diverse poor people of the city.

Between 1615 and 1622 the premises we know today at the ‘Six Poor Travellers’ on Rochester high street was used to accommodate at least ten orphans. {Why this was necessary, or why it appears to have ended this role in 1622 is unknown. Could it be that Rochester was left with so many orphans following the 1610 outbreak of the Plague that special provision needed to be made? By 1622 children orphaned in the 1610 outbreak would have come of age to work.} (Click image caption for more information.)

The accounts show there was another outbreak of the Plague at Rochester in 1636. They show that the Provider of the charity was unable to collect / buy the cloth made by the poor due to households being infected by the Plague. {The Plague was clearly disrupting the usual business of the charity and probably others. Whether the household was being isolated or being avoided is unclear – but the outcome was the same, social-distancing.}

1665 – coping with the large number of Plague deaths

Rochester, along with most significant towns and cities, did not escape the Great Plague that “raged to an alarming extent in the city during 1665”. (Click for- Descriptive sketches of Rochester). In the parish of St. Nicholas alone, it was recorded that upwards of 500 bodies were buried between April and Christmas. With the number dying faster than the living could cope with, the Mayor of Rochester swore-in three women on 14 July 1665 to undertake the role of ‘Searcher of Dead Bodies’; they were Margaret Walker and Joan Griffin for the city, and Elizabeth Brown for Strood. (History of Rochester, Frederick Smith. Page 165.)

Isolation / Pest Houses

A statute of 1665 required parishes to have a place where those who had an infectious disease could be sent. These became known as Pest Houses. It is possible that they existed before 1665 but they became a statutory requirement at the time of the Great Plague. Rochester’s Pest House was on the site now occupied by the Watts Alms Houses on the Rochester / Maidstone Road. {I’ve yet to discover when it closed but it was being used for housing in 1857 when the site was acquired by the trustees of ‘new’ Richard Watts Charity.}

In 1666 it was reported that the Plague had reached Chatham – and was spreading fast. Thirty people had died in one week and 100 households were infected. An observer of the time complained about the lack of ‘self-isolation’ – “No order is preserved and the sick and well promiscuously visit each other”. (Cited in The Story of Chatham, James Presnail. 1952, page 122.)

19th Century – Cholera arrives in Britain and Medway – importance of isolation, impact of loss of income, and hygiene, recognised.

Following an outbreak of cholera in 1832 at Chatham Dockyard, the Admiralty directed that if any workman be taken with cholera in the dockyards, he shall immediately be placed in hospital, and if any individual of his family should have the complaint, then he is not to attend the yard during the time the disease is in his house, but shall receive his pay the same as if he had been at work. (28 February 1832 – Maidstone Journal and Kentish Advertiser). Click for more information on outbreaks of cholera and typhoid in Kent.)

In the same year handbills were distributed by the authorities in Rochester detailing the precaution to be taken to prevent the spread of the disease. These included destroying the bedding and furnishings of someone who contracted cholera. (28 February 1832 – Maidstone Journal and Kentish Advertiser).

Quarantine Station established on the Medway

Long before cholera was brought to Britain diseases such as smallpox and scarlet fever were prevalent. The risk of sailors disembarking with these diseases – and probably others – was recognised, and control measures were put in place.

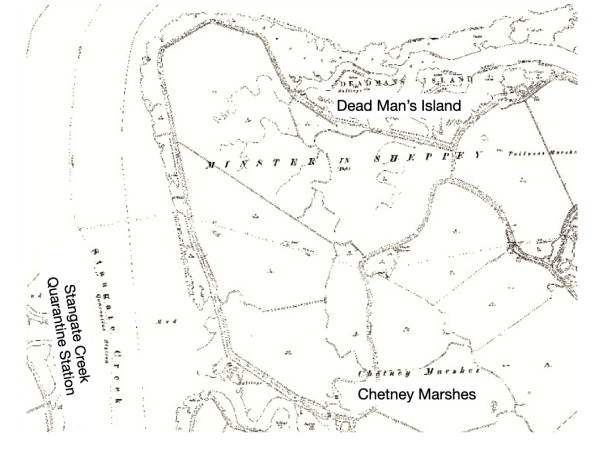

In 1799 regulations were passed requiring ships arriving into the Medway from an infected port, to make their way to Stangate Creek (near Iwade) where they would be held in quarantine and, if necessary, smoked and fumigated.

Here a quarantine station was set up for the reception and provision of quarantined personnel. It included tents and huts on the beach. (30 November 1799 – Caledonian Mercury).

{Over the decades hundreds must have died here as evidenced by the number of bodies being exposed on ‘Dead Man’s Island’ on Chetney Marshes – that is next to Stangate Creek. The fact that not just convict ships were quarantined in this creek raises the question whether, as is claimed, that all the bodies buried there are of convicts. Bearing in mind the great urgency placed on burying those who died of disease – would the authorities really have risked bringing a corpse ashore for burial?} (Click on image caption for video.)

{I’ve been told by someone who has visited ‘Dead Man’s Island’ that some of the remains show that legs had been broken to enable them to be fitted into a coffin. Could this indicate that the death rate was such that there was insufficient wood to make the number of full-sized coffins needed?}

The work of the Quarantine Station at Stangate Creek was supported for a number of {unspecified} years by HMS Duncan that acted as a hospital ship.

In 1863 when it was broken up at Chatham Dockyard there seems to have been some understandable reluctance shown by some on the men to undertake the work because of the ship’s association with contagious diseases (5 October 1863 – Morning Post).

Major political reforms lead to improved ‘health services’ in Medway

During the late 18th century there was an almost continuous demand for the reformation of central and local government. These demands were largely unheard until the end of the Napoleonic War in 1815.

With the end of the war there was a mass demobilisation of men from the army and navy. Many returned to Kent to find their jobs had been replaced by machines. Further, the landowning MPs were keeping, via the Corn Laws, the price of wheat / bread high. They had also passed ‘enclosure laws’ that enabled landowners to take control of large trances of land – evicting many farmers and stopping the ‘free-grazing’ on what had traditionally been common land.

The poor were stuck between a ‘rock and a hard place’. They had nothing to loose when faced with death from starvation. A rebellion not dissimilar to the French Revolution was feared. The Government could no longer ignore the voices of the ‘Radicals’ (Liberals) – and none were louder than those emanating from Rochester and Chatham.

In 1832 the Reform Act / Great Reform Act was passed which changed the British electoral system. This was followed with the Municipal Reform Act 1835 that extended the number of people who could vote. {As an aside, it was this law that ‘removed’ the right of women to vote as the legislation defined a voter as a male ratepayers. Accident in drafting or intentional? Either way I feel that the ‘exclusion’ of women had a detrimental impact on the early shaping of our health & welfare system – and in time led to many preventable deaths of children. (e.g. Claims that Rochester is failing its mothers – 30 June 1917, Chatham, Rochester & Gillingham Observer.}

The new principle of increased local accountability was applied with the passing of the New Poor Law in 1834. This Act required parishes to cooperate in creating a central workhouse/union – the working of which was to be overseen by an elected Board of Guardians. {Although presented in this blog as a positive step, some of these workhouses became places of dreadful cruelty – locally as well – but that’s for a future blog.}

The Municipal Reform Act also had a significant and lasting local impact on the running of the Richard Watts Charity. Up until this Act the Mayor of Rochester was free to manage the charity’s assets as he saw fit – a position that the local ‘radicals’ (reformers) felt he abused. Under the Municipal Reform Act the management of the charity was removed from the mayor and passed to a group of Municipal Trustees – who were later accused of ‘looking after’ their ‘mates’!

In 1835 the Medway Union appropriated the workhouses of St.Nicholas (Rochester) for the reception of the pauper children and youths of the united parishes, and that of St. Margaret’s (Rochester) for able bodied paupers. The Chatham Poor House was used for the aged, the infirm, and sick, (10 October 1835 – West Kent Guardian) thus creating a hospital/infirmary for the sick-poor. {The Chatham Poor House was located roughly on the site of the Gala Bingo Hall in Chatham(ME4 4NR). It predates the workhouse that was built in Magpie Hall Road in 1859 (See workhouses – viewed 31 March 2020) – part of which is now used as the All Saints Sure Start Children Centre. The 1896 OS map of Chatham shows a large infirmary on the site. The St Nicholas workhouse is gone but was on land close to Haywards House in Corporation Street, Rochester. The St. Margaret’s workhouse is now used by Kings School, Rochester.}

In 1854 the Government sent Charity Commissioners into Rochester to look at how the ancient charities of Richard Watts, the Kings School and St. Bartholomew’s hospital were being run. The Commissions found all was not well and proposed new and related schemes for the Richard Watts Charity and St. Bartholomew’s Hospital. The new schemes adopted in 1855 made a significant contribution to improving healthcare for the poor in Medway.

With the scene set ….. healthcare facilities began to be developed in Medway

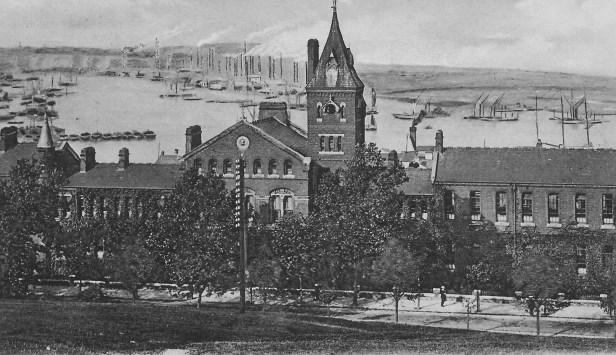

Melville Hospital – the first ‘Isolation’ hospital in Medway? Work commenced on the building of the Melville Hospital in 1827. It was on what is now the site of the Melville flats in Dock Road, Chatham (TQ759 687) and could accommodate 252 patients.

The main causes for admission were apparently cholera, typhoid and smallpox. As it would admit sick / injured dockyard personal it would have made a significant contribution to the local civilian population. The Melville Hospital closed in 1905 when the naval hospital (now the Medway Maritime hospital) opened.

The Rochester Dispensary in Nag’s Head Lane opened in 1832 (9 October 1837 – Public Ledger & Daily Advertiser; 30 October 1847 – Kentish Independent). I’m grateful to a ‘correspondent’ for finding and sharing the evidence that the house now known as Lindon House in Nags Head Lane, housed the Rochester Dispensary until it closed with the opening of St. Barts.

{Over the centuries the word dispensary has changed in meaning. At this time it was a charitable institution that provided medical advice and medicines – free or for a small donation. The services of the dispensary were meant to be restricted to the deserving poor as paupers and beggars could access help via the workhouses.} The Rochester Dispensary opened at a fortuitous time as the first outbreak of Cholera reached Medway early in 1832 (The History of Cholera in Great Britain. E. Ashworth Underwood. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 3 Non. 1947), (15 November 1832 – Maidstone Journal and Kentish Advertiser). [The dispensary closed when the Towns were “blessed with St. Bartholomew’s hospital” that included a dispensary (7 December 1889 – Gravesend Reporter, North Kent and South Essex Advertiser).]

St. Bartholomew’s Hospital (Rochester) opened in 1863.

The building of the hospital was made possible by the Charity Commissioners directing that £4,000 of the assets of Richard Watts’s Charity was to go towards the building of a hospital and dispensary, along with a revenue grant of £1,000 / annum to go towards its running costs. This amount was later increased to £1,500 and continued to be paid until the hospital was taken over by the NHS in 1948.

Community Nursing & ‘Health Visitor’ service – the Charity Commissioners directed the new trustees of the Richard Watts’ Charity to appoint five women as nurses. They were to care for residents in the new almshouse and older people, and laying-in women in the vicinity. This service was extended and run by the charity until 1950.

With increased facilities, disease outbreaks began to be anticipated and managed

A comprehensive approach began to be taken to tackling outbreaks of a disease that could reach epidemic proportions – we knew the steps that needed to be taken, and were being taken by the Navy. For instance, in 1847 following an outbreak of smallpox on a naval ship the infected men were moved to the an isolation ward at Melville Hospital, the rest of the crew were vaccinated, and the ship was sent to anchor at Gillingham Reach (30 January 1847 – Shipping and Mercantile Gazette). This demonstrated we knew what needed to be done – we just needed to build the resources and to apply some of the military discipline used to manage diseases on ships, to civilian populations.

Unlike infectious diseases such as smallpox and scarlet fever, the rapid spread of chorea in Medway was almost entirely due to poor sanitation. Concerns were being expressed in the press from the 1840s, about out lack or preparedness for a cholera epidemic, and that our backstreets “were places of filth and misery that act as bait that invites attacks of cholera and typhus – diseases that take more lives than those lost at the Battle of Waterloo” (19 October 1847 – South Eastern Gazette).

Many, such as Edwin Chadwick a social reformer, had been arguing that the cost of better public health measures would be more than covered by not having to fund so many poor because they were unable to work because of illness.

The cholera epidemic of 1848, that killed over 50,000 nationally, spurred the Government into action leading to the passing of the Public Health Act 1848, and the setting up of a Board of Health. Local implementation of this Act though was dependent on 10% of the rate payers agreeing. {It seems that Chatham took this on board, whereas Rochester did not.}

Cholera Outbreaks

Cholera did not arrive in Britain until 1831, but took off in epidemic proportions by 1832. In all probability it was brought in from overseas. When cholera arrived at Medway it found perfect conditions to become established. People, and convicts, living in overcrowded and insanitary conditions, with many people drawing water from the sewage-carrying river Medway, and other contaminated sources.

An outbreak of cholera on a ship seems to have invariably led to it being sent to the Quarantine Station in Stangate Creek. In June 1832 the convict ship The Cumberland (12 June 1832 – South Eastern Gazette), and the following month the convict ship, The Fanny, carrying female convicts from Woolwich (10 July 1832 – South Eastern Gazette), were both sent to Stangate Creek as they had cholera on board. Sadly the outbreak did not remain on the ships and soon there were many deaths in Chatham (10 July 1832 – South Eastern Gazette) “with much sickness prevailing in the neighbourhood” (17 July 1832 – Maidstone Journal and Kentish Advertiser).

The earliest reports of the 1848 Cholea epidemic reaching Medway – specifically Gillingham – was in December 1848 when 14 people living at the Copperas Houses, that boarded the creek near the wharf occupied by Mr Beeching at the Grange, Gillingham, contracted cholera – eight died. Presumably in an effort to curtail the spread, five were buried at 8pm (12 December 1848 – South Eastern Gazette). This outbreak spread across Medway. In February 1849 it was declared that the “village of Gillingham” was free from cholera, but that a few cases remained in Troy Town, Rochester (10 February 1849 – West Kent Guardian). There were further outbreaks in 1853, nationally and locally (22 October 1853 – Hereford Mercury and Reformer).

Medway’s “Health Services” takes shape

By the 1860s Medway was better resourced and organised to respond to an epidemic – increasingly able to take a proactive rather than reactive approach when an outbreak of an infectious disease occurred or was expected.

Melville Hospital was established; St. Bartholomew’s hospital was up and running by 1863 – providing wards and a dispensary; the new Medway Union was open with an infirmary, and Fort Pitt had been converted to a hospital {for it to have been selected by Florence Nightingale in 1860 as the initial site for a military medical school}; and there was an embryonic team of nurses employed by the Richard Watts Charity. {Although Fort Pitt was a military hospital there are news reports of it assisting the civilian population.}

Faced with a possible outbreak of cholera in 1866 (there had been 1,200 deaths in London in a period of one week), the governors of St. Bartholomew’s hospital made preparation for “the treatment of cholera patients in case the towns should be visited by that dreadful disease”. The governors erected a tent in the grounds of the hospital for the reception of cholera patients, and they agreed that all poor persons suffering from diarrhoea would be supplied with medicines without any nominations being required” (20 August 1866 – Maidstone Journal and Kentish Advertiser). {Prior to this exemption a person needed to be nominated for treatment at St. Barts by someone who was making a regular donation towards the running costs of the hospital, a vicar or a doctor.}

The Guardians of the Medway Union were not as proactive. Their clerk had obtained tenders for the erection of huts which could be used as wards if cholera reached Medway. But as the Guardians could not agree on wooden huts or iron-farmed buildings so they decided to turn the Labour Master’s House into accommodation for eight patients, and to defer further considerations until it was certain there would be an outbreak of cholera in Medway (18 August 1866 – Maidstone Journal and Kentish Advertiser).

When another outbreak of cholera was expected in 1871 the Rochester Corporation requested the Governors of St. Bartholomew’s to set aside a portion of the hospital for the reception of patients with cholera. The part of the hospital that was set aside was that which had formerly been used to detain and treat women, under the Contagious Disease Acts, who were infected with a venereal disease (STI). {During the 1860s there was an epidemic of sexually transmitted diseases in naval and garrison towns such as Chatham. In order to ‘protect’ the efficiency of the military, contentious laws were passed that enabled the enforced examination, and the detention of women found to be infected. (Click for blog covering St Barts Lock Wards).

In case the provision at St. Bartholomew’s proved insufficient the War Department agreed that a disused fort close to New Road, (Fort Pitt) could be converted into a cholera hospital (4 September 1871 – Maidstone Journal and Kentish Advertiser).

It is perhaps worthy to note that people who were not ‘poor’ continued to be treated at home by private by doctors.

Smallpox and other infectious diseases – outbreaks of smallpox caused panic

Limiting the outbreaks and spread of diseases such was cholera and typhoid was very much in the hands of the civil authorities who were responsible for sanitation. This was not so much the case for infectious diseases such as smallpox, scarlet fever (scarlatina), measles and influenza, where the spread was person-to-person, but would have been assisted by living in overcrowded conditions.

Of all these diseases smallpox seems to have been most feared. When St. Bartholomew’s Hospital opened in 1863 smallpox patients were amongst a group of patients who would not be accepted – they had to go to the infirmary attached to the workhouses. In 1867 there was outrage that staff from St. Bartholomew’s sent a patient with smallpox to the Medway Union using a public cab. (25 March 1867 – Maidstone Journal and Kentish Advertiser).

Specialist Isolation Hospitals Built – Eventually!

In 1870 there was a Public Health inspection undertaken in Chatham and Rochester. The stimulus may well have been the high death rate. When the numbers were put down to children dying of measles the inspectors recommended that consideration be given to building a fever hospital. This recommendation was passed to the Guardians of the Medway Union who appear to have not acted on it. (28 May 1870 – Chatham News.) In January 1877 it was reported that the Chatham Local Board of Health had appropriated one of the Martello towers in the New-road as a smallpox hospital. ( 22 Jan 1877 – South Eastern Gazette). {It is unclear whether this was ever used as the consensus was that a specialist hospital needed to be built.} The same report stated that the troops who had been vaccinated were free from smallpox – thus demonstrating the efficiency of vaccinations. {This snippet of information may have been reported to help address the reluctance of people to have their children vaccinated. See blog – Medway’s’Anti-Vacks.}

In December 1876 there was a smallpox outbreak in Chatham that “unfortunately” spread into the neighbouring towns of Rochester and Strood, (20 December 1876 – Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette), and appears to have become quite persistent. Some three months after the first report of the outbreak, seven people in a one week period needed to be sent to the workhouse (29 March 1877 – Edinburgh Evening News).

The building of St. William’s Hospital for Contagious Diseases

It was during the 1876/77 outbreak of smallpox that the Rochester Corporation decided that they needed to erect a Contagious Disease Hospital (20 February 1877 – The Star).

It was probably this decision that led to the building of St. William’s Hospital on what was then known as Delce Road. (Wisdom Hospice now on the site, ME1 2NU). It opened in April 1883, (Rochester, The Past 2000 years. City of Rochester Society) taking its name from a chapel that was once on the site.

Many infectious diseases – mostly not regarded as a serious risk today (but they are) used to ravage Medway. St. Williams soon become an essential facility in caring for people from Rochester and Chatham who caught, amongst other infectious diseases, the potentially fatal diphtheria, scarlet fever, or measles. There were too many outbreaks of these diseases to detail at length, but they all took many lives; further they did not necessarily ‘arrive’ one at a time – and the hospital could find itself overcrowded.

1882 – Diphtheria outbreak in Strood. In one family there were five children aged between three weeks to nine years all of whom went down with the disease. Four died and were interred in the same grave, the remaining child was admitted to the Isolation hospital in a critical condition (19 August 1892 – Kentish Mercury).

1883 – Outbreak of Scarlet Fever in Borstal – finger pointed at the prison. Fear that the poorly maintained prison drains was allowing the infection to spread from prisoners into the community (21 September 1893 – Maidstone Journal and Kentish Advertiser).

1895 – Measles outbreak at the naval depot at Chatham. All leave stopped. The order affected nearly 3,000 men (1 May 1895 – Manchester Evening News). {Shows how seriously measles was regarded.}

1895 – An “alarming outbreak” of diphtheria occurred at Strood, causing the isolation hospital to become “crowded”. Orders were issued requiring the bodies of people who died of diphtheria to be placed and screwed down in a coffin within an hour of their death (9 November 1895 – London Evening Standard).

1902 – Smallpox outbreak – see 20th Century below.

1912 – Typhoid outbreak at Strood with over 30 people infected. Military authorities at Chatham required all married men residing in Strood, belonging to the service to live in barracks (13 August 1912 – Exeter and Plymouth Gazette). The outbreak was traced back to an area known as “The Swamp and where flies had assumed the proportions of a plague”. The Joint Health Board decided to empty St. Williams in readiness to accept up to 100 typhoid patients (17 August 1912 – East Kent Gazette). This outbreak soon spread to Rochester and the Medway Union.

1920’s Diphtheria outbreak in Gillingham, Kent – a personal account.

Deborah G – wrote that her mother told her about her childhood experience of “being isolated at home in Gillingham (Kent) in the 1920’s during a diphtheria outbreak in the area. The doctor wanted her to go to the isolation hospital but her parents refused as she was their only child and kept her at home. All her possessions had to be destroyed and she developed the habit of ‘air writing’ as she wasn’t allowed paper and pencil’a habit that lasted all her life. Interestingly diphtheria was thought to have been caused by drinking raw (unpasteurised) milk”.

[It would appear the the doctor was right to be aware of the risks of raw milk. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (an agency of the EU) still advises of the risk of an unvaccinated person catching diphtheria through close contact with cattle, and eating raw dairy products. ECDPC Advice].

The destruction of the possessions of someone who had a highly contagious infection was well established. In December 1914 when the Mayor of Rochester made an appeal for toys for orphans and children in hospital, he specifically asked for cheap toys that could be burnt for the 40 to 50 children in St. William’s Hospital. (5 December 1914, Chatham, Rochester & Gillingham News).

20th Century – comprehensive response to outbreaks; technology introduced that saved lives

Resources ‘thrown’ at managing the 1902 smallpox epidemic – some rather desperate!

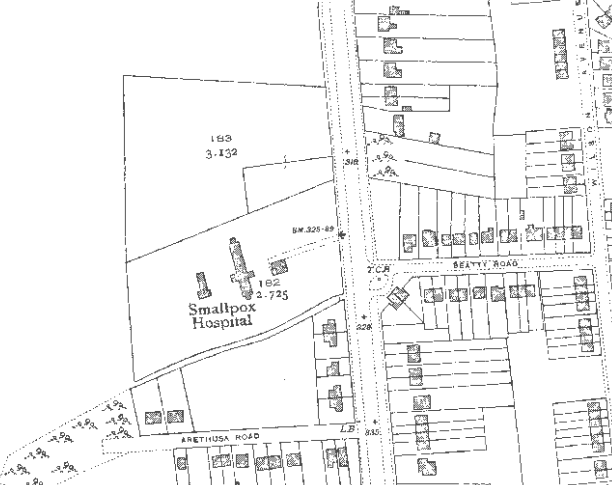

By the time of the 1901/02 outbreak of smallpox in Rochester the Rochester & Chatham Health Board was better prepared but soon found that they had insufficient capacity. It therefore took steps to urgently construct a smallpox hospital – which it was found needed to be extended soon after it opened. Such was the urgency for this hospital the Board needed to apply retrospectively for permission to borrow the £2,700 that it had borrowed to build the hospital (9 January 1902 – St. James’s Gazette).

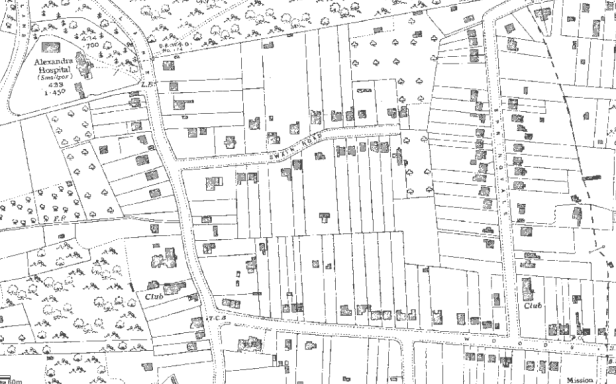

{The Rochester & Chatham smallpox hospital was on a site that is now the Bedgebury Close area off Friston Way / City Way, opposite the junction with Beatty Road, Rochester [ME1 2UT/TQ747 658]}.

A correspondent, Angela White, has kindly provided more information about what happened to this hospital, and about the construction of City Way based on her personal experience / knowledge:

“I was at the demise of the Smallpox Hospital located on City Way. The hospital building was where Bedgebury Close is now situated, although the entrance to the grounds was off City Way.

It was one of my earliest memories and it would have been around 1949-1950, I cannot remember exactly, when I was about 6 or 7 . One evening the Smallpox Hospital was went up in a huge conflagration which I, my parents and a lot of other residents stood watching on the corner of Beatty Road and City Way outside what is now the Post Office. The story going round at the time was that a group of local boys had set fire to it, whether accidentally or not I don’t know, but I am sure the site would have been a magnet for young boys.

Also, my understanding is that the bungalow, now, 492 City Way, was the residence of the superintendent of the Smallpox Hospital. When the hospital was built the bungalow would have been surrounded by fields and quite isolated in Dark Lane, which came up from the Delce.

It would have been about a quarter of a mile from the Fever Hospital, which was located about a quarter a mile down Dark Lane towards the Delce.

I have never researched it – but to me it makes sense – and that is that City Way (A229) was constructed in the late 1920s to create work during the Depression and joined the bottom part of Pattens Lane, starting at that time at the New Road, to the top part of Dark Lane by building a new piece of road from the Military Cemetery to where the George Public House (previously the Old George) now stands, making one road: City Way. The cut-off part of Pattens Lane – now a cul-de-sac named Old Pattens Lane – can still be found behind numbers 1-69 City Way.”

Gillingham also had an isolation hospital – the Alexandra hospital at Wigmore {on a site that is now opposite Swain Road off Hoath Lane, TQ797 648}.

It appears not to have admitted smallpox patients during the 1902 outbreak – preferring to first place them in a tent then a stable! A market gardener and his wife sought damages against Gillingham Council for using a stable to temporarily house a patient with smallpox – with the consequence their son caught and died of the disease. The patient was initially placed in a tent at the back of the Infectious Diseases Hospital but it was felt that this was too close to the hospital so he was moved to a stable on grounds owned by a member of the local authority (27 March 1902 – Sheffield Daily Telegraph). {They won their case.}

During the 1902 outbreak the Rochester Corporation also brought into use a hospital ship – The Elk – anchored on the Medway to quarantine relatives of those who contracted smallpox (3 April 1902 – Leeds Mercury). When Rochester was approached by the military, in January 1902, to make use of the Elk, they were advised the ship was already full with families removed from houses in which cases of smallpox had occurred. The report of this request also stated that consideration was being given to building more cabins on its decks – suggesting the ship was overcrowded. {The Elk was a damaged naval ship that the Corporation had purchased in 1893 apparently to isolate patients with cholera. It appears the ship could have been in poor condition as it sank at its moorings in the year it was purchased for £515 (5 December 1893 – Gloucester Citizen). The building up of the deck could be hazardous – there are news report of a local convict ship toppling because of such construction.}

Preventing the spread of smallpox in 1902 appears to have been most comprehensive. Not only was a special hospital constructed and a ship used to quarantine the households of someone who caught smallpox, but a range of other initiatives were put in place that required the cooperation of the wider community:

- The Rochester Watch Committee ordered all the police officers to be vaccinated – something that was soon rolled out across Kent (10 January 1902 – Yorkshire Evening Post).

- A vaccination programme was instigated – but must have proved to be very expensive as the Guardians of the Strood Union, presumably after the smallpox outbreak was over, terminated all vaccination contracts with local doctors following one claiming fees of £800 in a six month period (10 May 1902 – Reading Mercury). {Around £80,00 at today’s values.}

- The Workhouse Guardians refused to admit tramps who were unable to prove they had been vaccinated against smallpox (10 January 1902 – Yorkshire Evening Post). {I wonder if part of lifting the 2020 lockdown arrangements will require proof of some immunity to COVID-19?}

- The Richard Watts Trustees considered closing the Six Poor Travellers’ house but instead decided that men should be examined by a doctor before they were admitted.

- Regulations were enforced preventing the removal of undisinfected items from a smallpox household – Eliza King was fined fifteen shillings at Rochester for removing clothes from a smallpox stricken house without disinfection. Her plea that she acted in ignorance provided no defence (27 January 1902 – Lancashire Evening Post). {15s = 75p = approx. £75 today.}

As handbills had been used in the past one could perhaps assume public information was also provided.

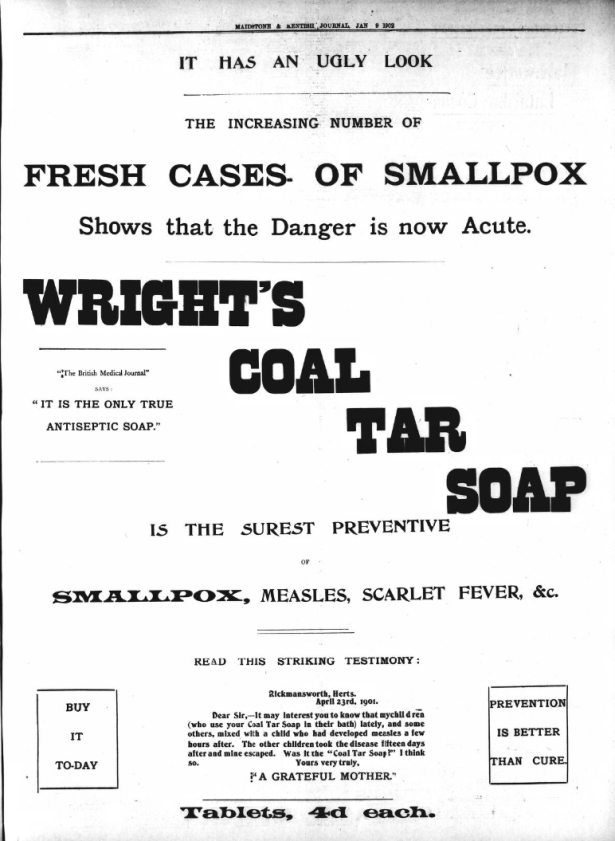

Partly to promote public health and partly capitalising on the panic engendered by the outbreak of smallpox, adverts appeared in the press promoting Wrights Coal Tar soap as a preventative to catching a range of infectious diseases – it claimed to have been endorsed by the British Medical Journal as “.. the only true antiseptic soap” (e.g. 9 January 1908 – Maidstone and Kentish Journal).

Spanish Flu overwhelms heath and funeral services

1918/19 saw the worst flu epidemic to hit the country. The timing could not have been worse – the situation was dire. The war had taken many young men, public / voluntary services were effectively ‘broke & exhausted’, and the virus was attacking the young more than the old.

Partial Lockdown instigated

The death rate locally steadily rose during October 1918 to double what was expected. All theatres, music halls and cinemas were placed ‘out of bounds’ to service men. All schools throughout the district of Rochester, Chatham & Gillingham were closed. With so many of the police at Chatham and Rochester being ‘down with the flu’ special constables were called upon to do regular police work (2 November 1918, Kent Messenger). The Mayor of Rochester was troubled by the overcrowding on the trams and felt ventilation should be increased and that no one should be allowed to stand in the middle of the tram during the crisis (2 November 1918 – Chatham, Rochester & Gillingham News). Whilst the schools were closed the Education Committees directed that they were all to be well ventilated, and to have their floors.

The death rate was such the local undertakers were overwhelmed. During October 1918 there were more than 60 internments in Fort Pitt Military Cemetery, at Chatham, and in the last two weeks of October 1918, 200 deaths were registered in the Rochester and Chatham Sub-district. To assist the undertakers 12 sappers were sent to Rochester to make coffins and to assist in burials (9 November 1918, Chatham, Rochester and Gillingham News).

Between the Wars, although probably always prevalent but masked by the likes of cholera, typhoid and smallpox, there were frequent epidemics of measles, whooping cough, scarlet fever and diphtheria.

In 1937 it was reported in a one month period, 82 people were admitted to St. William’s Hospital mainly suffering from scarlet fever or diphtheria. In an effort to reduce the pressure on the hospital the medical officer for Rochester pleaded for people to take up the vaccination for diphtheria, and for people to be isolated at home – reserving the hospital for those who needed treatment (12 May 1939 – Chatham News).

Health technology – Polio drives the development of Life Support Machines

A stepped-change clearly occurred with the the extensive roll-out of vaccines. A flu vaccine was being developed in the 1930s, and a vaccine was available for diphtheria by 1937.

The next stepped-change came with the use of technology to sustain life while the body fought an infection. It came in the form of the Iron Lung that assisted a patient’s breathing. Click on image caption for video.

A significant new disease appeared on the scene in the 1930s – initially mainly in America, but it soon spread – Poliomyelitis (polio). This was a virus that attacked the nervous system and could cause temporary and permanent paralysis. If the virus attacked the nerves that controlled the chest muscles the patient would not be able to breath. This led to the invention of the Iron Lung. Effectively a sealed box into which the patients’ body would be placed. Through the cyclic raising and lowering of the air pressure in the box, air was drawn into and expelled from the patients lungs – an early form of respirator. In a short time most patients regained the ability to breathe for themselves. It was effective and cheap to make. However in the 1930s they cost about £1,000 / machine and required an electric supply – costs beyond the reach of hospitals funded by voluntary subscriptions and donations. In stepped Lord Nuffield – previously known as William Morris – the car manufacturer. So impressed by the effectiveness of the Iron Lung he turned part of a factory over to manufacturing them – using car parts if they suited. He donated over 5,000 machines around the world. (Click on image caption for video of one of the first Iron Lungs.)

An Iron Lung under the Nuffield Scheme was donated to St. William’s hospital in 1939. The hospital though did not have an electric supply so the hospital board needed to obtain tenders to resolve that problem (19 May 1939 – Chatham News).

St. Bartholomew’s hospital also appears to have received an Iron Lung, as in 1939 its machine was rushed to Keycol Hospital (Sittingbourne) in a furniture van, to sustain the life of a seven year old boy who had contracted polio. When it arrived it was discovered that the hospital’s voltage was not the one needed for the machine – a problem that was quickly resolved by engineers from the Kent Electric Power Company (11 August 1939 – Chatham News).

Polio – 1950’s – a personal account

The following purple text is based on the personal experience of someone who read this blog – but who wishes to remain anonymous so I refer to her as ‘my correspondent’. Her story is personal, moving and informative; the detail of her recall of events that occurred over 60 years ago shows how traumatic the experience must have been.

I found reading her account a privilege – and I hope you will as well – it’s a reminder that behind statistics and historic events – there are human stories.

“At Easter 1958, my correspondent, then a seven year old girl, was recovering along with her six year old brother, from chickenpox. One day that weekend she found it difficult to stand up, and when she tried to walk across the room she kept collapsing. When she reported that she could not feel her legs a doctor was called. He diagnosed polio, and arranged for her to be admitted to St. William’s Hospital.

The Fever Ambulance

A fever ambulance was called – it was unlike the usual ambulance in that it was painted bright white and had black windows. The ambulance men were dressed from head to toe in long white gowns, gloves, masks and hats. The whole experience was frightening and distressing. In order to comfort my correspondent her mother gave her a stuffed toy rabbit that had sat on her dressing table – so precious was this toy it is still treasured today.

St. William’s was, as far as my correspondent was concerned in a foreign country but she recalls being driven up a steep slope, and taken to a large room under a sort of awning. The room had nothing but a bed and locker, a wicker chair and a fireplace in it. At each side of the room was a window overlooking a covered passage on one side and a grassy bank on the other. There were a number of rooms in a long row with large glass panels dividing them. At the end of the row of rooms was the nurses’ station.

Once settled in her bed her parents departed, and that was the last physical contact she had with them for two months; they though could visit some evenings and talk to her through an open window at a distance of about eight feet.

My correspondent recalls being examined by doctors and her legs not responding to the reflex tests “[my] left leg failed to react and was quite dead”. With the help of a physiotherapist movement was restored and she was eventually able to walk again. When she was regarded as no longer being infectious she was allowed to play on the grass bank outside of the ward – but she had to return to her bed to ‘receive’ visitors.

Children’s nurses admitted from All Saints admitted to St. William’s as patients.

The ward that my correspondent was on, was busy with others being admitted mainly with scarlet fever. She also recalls nurses being admitted from the Children’s Ward of All Saints with chicken pox which had spread through the towns like wildfire.” {I had chicken pox as a young adult – I can vouch for it being nasty – it’s nothing like the disease that many youngsters seem to ’throw-off’.}

“When ready for discharge my correspondent was taken home in an ordinary ambulance.

The story of her brother was less fortunate. A few days after my correspondent’s admission to St. William’s her six year old brother developed difficulty with breathing and was admitted to All Saints Hospital – perhaps because it had a iron lung? It was found that he had developed bulbar poliomyelitis as opposed to the paralytic variety that his sister had. Tragically he died on the night of his admission – his parents being informed by telegram.

Fever Ambulance / Van / Cart

I am grateful for this above memory as it revealed to me another aspect of how we managed highly contagious epidemics – The Fever Ambulance, also known colloquially as the Fever Van or Fever Cart. {Above I record the outrage when staff at St. Barts send a smallpox patient to the Medway Union in a cab.}

The Fever Cart was disliked and feared – it could mean that a child was being forcibly removed from their family and with the distinct possibly they would not return – as illustrated in the following account. (Click for details – The Fever Van.)

These vehicles were in existence throughout the country from around 1910 to the 1950s and had various nicknames. Helena M Thomas from Rainham in Kent remembers a trip in one in 1918: {Helena was not my correspondent.}

‘”The Fever Cart was a frequent visitor to Rainham in the early part of the century and although we children held our noses as it went by—many of us became passengers in our turn…. I remember being bundled up in a red blanket and lain head to the front in the little cab. I was probably too ill to notice much of the journey… but I do remember the bumps of what I thought was the horse kicking the cab by my head’.

Helena goes on to to recall: ‘The health inspector arrived at the house to fumigate the bed and the room I had occupied. I spent a month in North Ward [of Keycol Hill Isolation Hospital] and my mother was allowed to stand on a chair outside the window and see me in bed on Sunday and Wednesday afternoons“. (Bygone Kent 1999;20(3))

Houses Disinfected/Fumigated

My correspondent who recounted her experience when she caught polio did not write about what happened at home after she was admitted to hospital, but there are accounts of houses being destructively disinfected following the removal of a child with an infectious disease – “The child’s books and toys were to be destroyed, its bedroom disinfected by the application of concentrated solutions of powerful germicides to the floor, bed, walls and furniture. Wallpaper must also be stripped and burned’. These procedures caused much disruption and discomfort for the household. (See Fever Van link above). {This would have been extremely upsetting – particularly if the child did not survive. It could have also been costly to the poor who may not have had the means or the insurance to repair and restore.}

I am grateful to Rosemary Clemence for the reminiscence of her father Norman Clout (1914-1997) who caught scarlet fever. It shows how life-threatening a ‘childhood’ illness could be. It also confirms that the Rochester Smallpox Hospital did consist of iron clad buildings, and that the rooms of people admitted to hospital with a contagious disease was fumigated.

In 1930 “I went down with scarlet fever. Today this would be a minor incident. Then it was a major disaster. I was wafted away to isolation at St William’s Hospital, Dark Lane, Rochester. My bedroom at home was fumigated by the health authorities, and, instead of the normal four weeks, I spent eleven weeks in hospital. I was unlucky enough to contract practically every known complication, and, so I was told later, nearly expired from nephritis (kidney trouble), which apparently I already had without knowing it. Twice a week, when well enough, I was allowed to stand on the terrace and wave to my parents down yonder in the road. At that time St Williams’s was a Fever Hospital, purely for cases of scarlet fever, diphtheria and the like – which were all very serious matters. On the site of the present Warren Wood School for Girls, higher up the modern road, stood a small corrugated-iron building which was the Smallpox Hospital, but that, in fact, to my memory, was rarely used.”

Track & Trace

In 1946 a ship known to have had smallpox on board disembarked 28 passengers. The authorities quickly put arrangements in place to ensure their whereabouts was known and to be quickly alerted if one was to display symptoms. Presumably they would have quickly been sent to the isolation hospital.

In Summary – the evolution of our health service – driven by epidemics?

{It is interesting to note how much of the following are being used or pursued today as we combat the progress of a coronavirus.}

- 1088 – Exclusion- leper houses

- 1636 – Avoidance – Watts provider would not call at houses with the plague

- 1665 – Plague – Isolation – Pest hospitals / houses – affording infected and potentially infected people

- 1799 – Quarantine Station – for ships arriving from ‘diseased’ ports

- 1832 – Protection of pay / public information

- 1835/1863 – Hospitals / workhouse infirmaries

- 1855 – Community nursing – Richard Watts’ Nurses

- 1883 – Isolation hospitals

- 1902 – Multifaceted programme to constrain the spread of smallpox – including disinfecting houses / burning potentially infected items.

- 1912 – St. Williams hospital emptied in anticipation of an influx of typhoid patients

- 1939 – Initiatives/pleas to protect hospital capacity

- 1939 – Life support technology deployed – enabled by industry

- 1946 – Close monitoring of 28 people in Gillingham who disembarked from a ship that had smallpox on board. Plans to set aside a ward at Keycol or St. William’s.

- 1948 – NHS / National Coordination

21st Century – We face the pre-vaccine challenges of the 19th century!

COVID-19 arrives for which there is no vaccine. The numbers who could be infected would overwhelm hospitals, and the number dying would overwhelm funeral services – and may already have done so in some areas with temporary morgues being set up.

Today’s attack plan that includes heightened hygiene regulations/regimes, social distancing (avoidance) and self isolation (quarantine), all aimed at ensuring services are not overwhelmed and that there is sufficient equipment to save those who do become infected, are almost identical to that followed by our predecessors during the past 400+ years.

In Memoria

Advances in medicine and science clearly enabled the development of our heath service – but the services are delivered by people. During my reading I came across some remarkable stories where health professions put their own lives on the line to save lives or reduce the distress of a dying person. The account above of the personal memory of a young girl admitted to St. William’s with polio, tells of nurses from All Saints Hospital being admitted to St. William’s with chicken pox.

There were many reports of health professional losing this lives or catching a disease from their patients, but they were seldom named in the news reports. I did though find two named nurses, and I record their story here in the hope they will be ‘discovered’ by search engines such as Goggle, and in turn, by a descendent who may be working on their family history.

Nurse Finns – senior nurse at St. William’s Hospital (Rochester) 1888:

“Heroism of a Nurse”: A two year old child was admitted to St. William’s Infectious Hospital suffering from a bad form of diphtheria. An emergency tracheotomy was performed. “During the night the tube became clogged, and the poor little sufferer was found gasping for breath. Death being imminent, one of the senior nurses, a young woman named Finns, bravely offered to suck the tube, a task attending with almost certain risk of her life. Notwithstanding urgent representations made to her as to the danger attending such self-sacrificing conduct, Nurse Finns applied her lips to the tube and thus prolonged the child’s life for several hours.” (2 June 1888 – Whitstable Times and Herne Bay Herald.)

Sister D Mathew – Strood VAD hospital – 1918:

“Influenza claims Sister D. Mathew, matron of the Strood VAD, who worked unsparingly whilst ill. The management committee of the Strood & Frindsbury VAD hospital, with great regret, announced her death. The influenza epidemic claimed a large toll of victims among the nursing staff of this VAD hospital, which particularly for one week threw a great burden of heavy and trying work and long hours upon those left available. Sister Mathew was unsparing of herself and worked on and on when undoubtedly she should have been in bed. But she knew that no other nurse of her trained professional ability was available and she continued to work until her physical powers failed and she was ultimately obliged to take to her bed. She was buried in Cobham, Surrey, but a memorial service was also held in the Choir of Rochester Cathedral.” (14 December 1918, Chatham, Rochester & Gillingham News.)

Concluding thought

No one today has experienced or lived through an epidemic of the magnitude of COVID-19. An epidemic that could decimate a population, overwhelm care services, and destroy economies.

What is happening now with COVID-19 was anticipatable. Scientists have been warning that bacteria are becoming resistant to antibiotics. Although a virus cannot be killed by antibiotics the impact of this virus is no different to that we would have experienced had the ‘attack’ come from a nasty antibiotic resistant bacteria.

Were we ready? Did we anticipate and prepare in the same was as our predecessors? Could we / should we learn from the past and develop capacity to deal with “what could be” as well as “what is”?

Perhaps the lesson here is that we need to learn more from history – than JUST learn history.

Geoff Rambler / Ettridge

April 2020

Comments are closed.