Christmas in the Tudor Household of Eastgate House, Rochester.

The following is speculative. Facts have been checked, but my presentation of their potential significance is speculative.

—————————

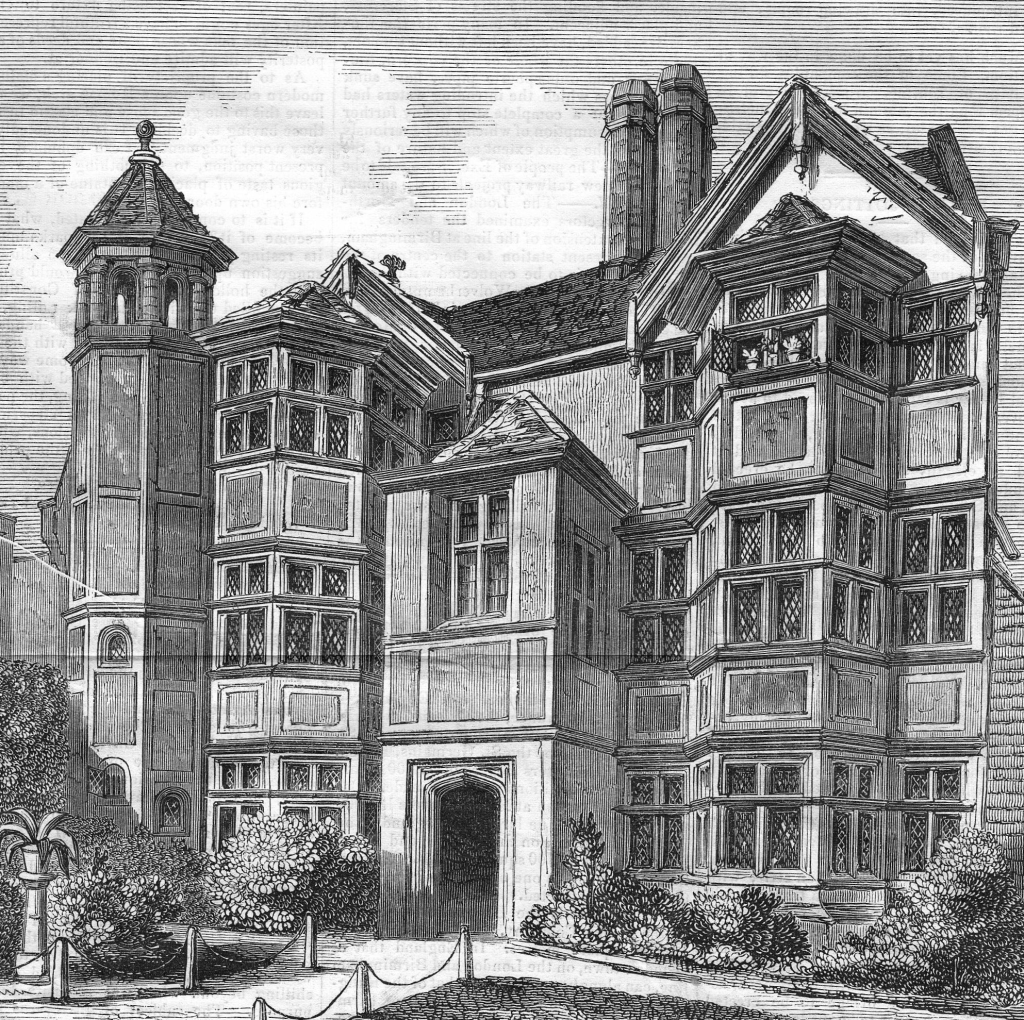

Many pass and visit Eastgate House at Rochester. Most will be struck by its architecture, but it started ‘life’ as a family home. The first occupants were Peter and Mary Buck, who commissioned the building of the house in the 1590s. The following is a speculative account of how Peter Buck may have celebrated Christmas shortly after moving into Eastgate House.

The Christmas period in Tudor times extended from Christmas Day to Epiphany (6th January). Certainly, it was a time to attend church. Failure to do so would have been noticed. But Christmas for wealthy people in the late Tudor period was about much more than a religious observance.

The period would have been joyous and fun with the family. However, for the wealthy, it was a time to show their largesse. This would have involved acts of generosity to staff, the poor, as well as towards influential people. At a time when business was done more on credit than cash, making good connections with people of influence was important. The spirit of Christmas and the duration of the holiday would have lent itself to ‘networking’ and demonstrating and perhaps enhancing one’s social standing.

Peter Buck’s Christmas? Early 17th Century.

The following is a synthesis of historic information. It is based on the assumption that the upper middling class of the 17th century styled their households like those of the aristocracy. There’s much in the design of Eastgate House that matches aspects of the home of an aristocrat. There was at least one tower, there were ornate plaster ceilings, and a zoning of areas – public, business, and private. (The tower that we see today has been reduced in height. There may have been a second tower. They contained a spiral staircase.)

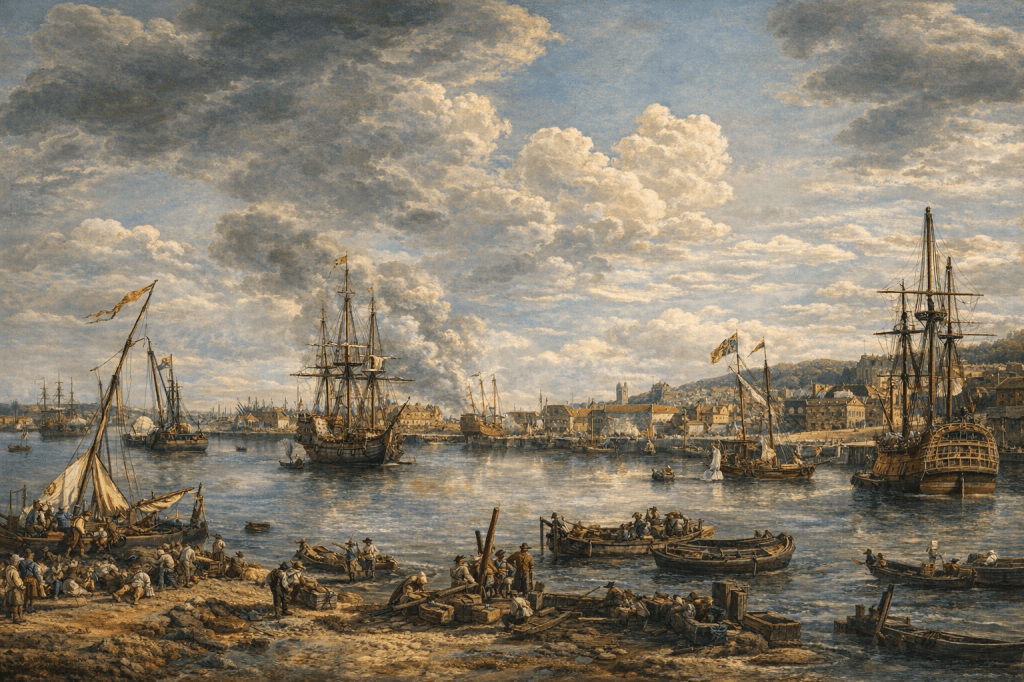

Little is known of Peter Buck, in Kent, prior to him commissioning the construction of Eastgate House. He could well have been new to the local social scene. Business-wise, as Clerk of the Cheque at Chatham Dockyard, he was in a pivotal position. His responsibilities as a senior administrator would have brought him into contact with senior people from the Admiralty. He would also have interacted with senior dockyard workers. As the dockyard, at this time, was not a Crown asset, he would have probably needed to work with the civil authorities and local businessmen and landowners as the dockyard expanded. His position would therefore have given him influence, and others may well have wanted to influence him!

The week before Christmas

This would have been a period of intensive activity. Twelve days of festivities for a wealthy family would have required considerable preparation.

Provisions

There would have been bulk purchasing of meat – beef, mutton, chicken, and geese. Spices and sugar would be acquired. These would have included nutmeg, cloves, and ginger. It is possible that Peter Buck would have had ‘connections’ who could have provided these luxuries. There would have undoubtedly been alcohol available – wine and a spirit we know today as brandy.

The provisions would have been delivered to the entrance of Eastgate House. Not the side entrance we see today, but the one that faced onto the high street. Where it was located can still be seen. The location of this door is farmed in red. High street level has increased over the centuries.

Food Preparation

This entrance in the early 17th century, before the house was extended, would probably have been into the kitchen/kytchyn. The high, narrow window facing onto the high street, which may not have been glazed, was probably not about affording privacy, but the solution to practical problems.

The high street at this time would have been muddy and mucky. Splashing by passing traffic in wet weather, and dust blown up in dry weather, would have been a serious nuisance. The high window would have afforded some protection. The high window would have also created more wall space, that would have increased the utility of the room. [Interpretations at Eastgate House say this room was Peter Buck’s study. I wonder if this came about as Tudor documents distinguished between the ‘Main Hall’ and ‘Offices’. The offices included rooms such as the kitchen, scullery, and larder, etc. The main hall would have been the household’s space. I suspect during the first phase of the building of Eastgate House, the large room on the first floor, with the heraldic plaster ceiling, could have acted as the main hall.]

Food preparation would have been undertaken in the ground-floor room. The preparations would have included making marchpane (marzipan), baking mince pies (made with ‘animal’ meat, not fruit), and gingerbread. As ale at this time had a short shelf-life, it was probably brewed on site.

The meat joints would be roasted on the day they were required – probably everyday!

Entertainments

Assuming that the Bucks did not have musicians on the staff, they would have needed to book them along with other performers.

Decorating the House

Outside, doorways and windows would have been adorned with holly, ivy, and other greenery. The first and second-floor family rooms would have shared this greenery but also featured aromatic sprigs of rosemary and bay. Candles, perhaps a few more than usual, would have been lit or arranged decoratively. These candles symbolised light entering the world and might have been left burning overnight to bring blessings and protection to the household.

Christmas Eve – Preparations almost completed.

On Christmas Eve, before the commencement of twelve days of festivities, loose ends would have been tied up. Household staff would have added finishing touches to the food and probably brought in a Yule Log. [We know from a dispute that Peter Buck had with a neighbour that the house had a chimney.]

Peter Buck would probably, that day, have finalised business and administrative duties that could not wait until after the holiday.

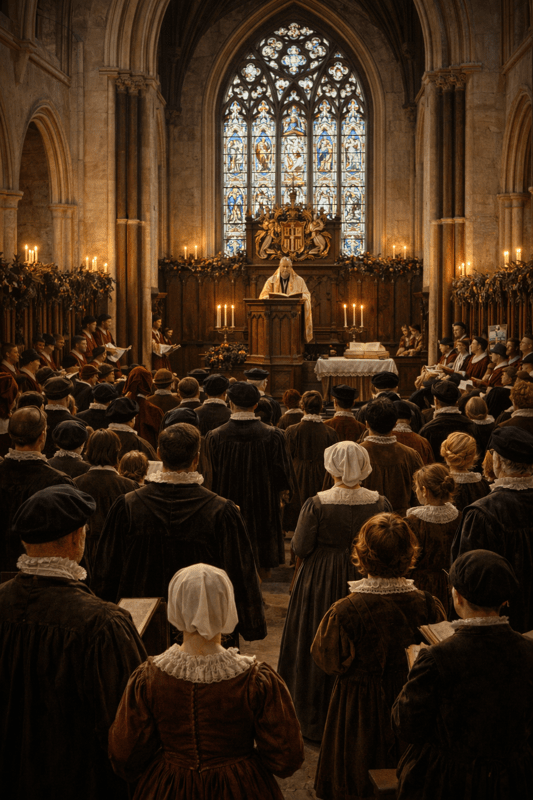

The day probably ended with the family attending an evening church service. Clocks were not widely available then. Instead, they would have heard the church bells summoning people to the service. The service may have been later in the day but not midnight. The midnight service, we know today, was regarded as ‘popish’ and was discouraged by Elizabeth I.

Pews were not widely installed in churches in the early 17th century. The congregation largely stood. It is, though, possible that wealthy people had cordoned-off areas that may have had some seating. It’s unknown if this was the case at Rochester at this time.

As services were longer than we generally experience today, the Bucks may have been pleased to get home afterwards to take the weight off their feet. The Bucks may well have also been in need of a ‘festive drink’ to warm up. Winters in the early 17th century were harsh, with climatologists describing the period between 1560 and 1640 as a “Little Ice Age”.

The Holiday Begins

Christmas Day

This was not the Tudors’ day for exchanging gifts and presents.

The day would start with attending a church service – in one’s best and warmest clothes. The cathedral was in a state of decline following the Reformation. However, it was still adequate for Elizabeth I to attend Divine Service in 1573. Peter Buck would probably have chosen to attend a service in the cathedral rather than one of the local parish churches – St Nicholas, St Clements, and St Margarets – as he was more likely to meet dignitaries.

The service would have been sung, and a large part of it taken up by the sermon. There are apparently texts of sermons delivered at this time, running into over 40 pages. In the margins, there were marks suggesting these were aid memoirs for a digression.

Following the service, the Bucks would probably have returned home. Here, they would formally greet household staff and distribute small gifts such as coins, clothing, or food.

At midday, the feasting began. The assembled would have tucked into the food prepared during the previous week and roasted that morning.

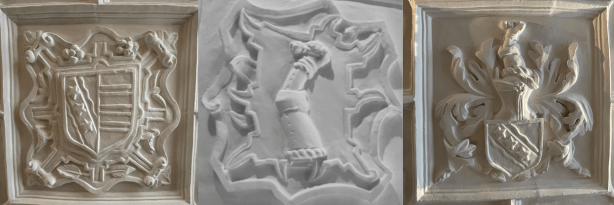

I suspect the Bucks and friends would have feasted in the large room on the first floor. The curators of Eastgate House have labelled this the ‘Family Room’ – but that I believe it could have been Peter Buck’s room. It’s the largest room in Phase 1 of the house. It is large enough to be furnished with a large table, and the heraldic devices in the ceiling’s design would have left Peter Buck’s guests in no doubt of his civic status!

The evening probably concluded with more eating and drinking. Entertainers would perform, or the family would participate in what we know today as parlour games or readings. What was read would have depended on how pious Peter Buck was.

St Stephen’s Day (26 December) – now Boxing Day

This was the day on which servants, tradespeople, and the poor were presented with gifts. This was a way of establishing the social hierarchy within communities. Failure of a wealthy person to provide alms could attract censure from the community and church.

Giving of Dole

Alms giving would have been essential during the reign of Elizabeth I. The Reformation was initiated by her father, Henry VIII. It had closed the monasteries that had previously provided for the poor and infirm. Donations to the church had also diminished to the extent that Elizabeth I wrote to the wealthy requesting they remember the poor in their wills.

Peter Buck would have been acquainted with the needs of the poor in Rochester. This probably led to him being appointed by the Mayor as the Provider to the Richard Watts Charity in 1608. He held this position for one year. He held this position for one year. (Detail from unpublished transcript of Watts Charity accounts.)

For more about Richard Watts and his charity click Richard Watts.

In the role of ‘Provider’, he would have been responsible for overseeing the running of the travellers’ house and ensuring materials such as wool and flax were distributed to the poor. These would be woven into cloth, which was purchased from the poor households. Income from the sale of the cloth was used to purchase more raw materials. This established a virtuous cycle— that operated well all the time the households were not afflicted with the plague, chorea, or suchlike! (For more about Medway Plagues click Epidemics.)

Peter Buck may well have visited the poor in the neighbourhood. There is no evidence that he was a landlord, but if he was, he would have visited his tenants. He would have distributed food left over from Christmas Day. He would have also given coins and food parcels containing meat, bread, and ale. This was known as giving of ‘dole’—a term that remained in use for a long period for unemployment benefit.

It is also possible that Peter Buck would have given extra provisions to the travellers’ house that was also the City’s almshouse. Again, his gifts may have included extra food, clothing, and fuel.

St John’s Day (27 December)

This was a day for hosting friends, family, and close business associates with gift-giving. An Artificial Intelligence source suggested Peter Buck’s friends could have included Sir Francis Drake and Sir John Hawkins. When challenged, it was accepted there was no evidence to support this, other than they could all have been active at Chatham at the same time.

Holly Innocent’s Day (28 December)

This was a day of fun and frivolity, and included lighthearted events that involved role reversal. Children and apprentices would be indulged, and people in senior positions could be mocked. Such mockery could have been the appointment of a choirboy as a ‘boy bishop’, or a junior member of the household assuming the role of a more senior member.

29 – 30 December

Unless there was a requirement for Peter Buck to attend to business, the holiday would have continued with fun, entertainment, and other leisure actives – and presumably continued eating. The opportunity would probably have been taken to further associations and connections with other businessmen and merchants.

With the distribution of dole, the benefactor demonstrated their largesse and standing in society. Through the hosting of peers and business associates, there would have been the subliminal demonstration of the host’s business prowess. This would have been important in the Tudor period when the economy was less about cash and more about trustworthiness and access to assets.

Who could have appeared on Peter Buck’s ‘Christmas List’?

As Clerk to the Cheque at Chatham Dockyard, Peter Buck would have been at the ‘crossroads’ of many interests. He would have wanted to ‘keep all of them on side’. Without the benefits of LinkedIn and other social media, Christmas would have provided the perfect opportunity to build more personal links. It was a chance to connect with people who could facilitate business and his career advancement.

People falling into these groups could have included the following – although there is no evidence that shows any formal connections. But I speculate they could have included:

- Members of the Admiralty – Sir Francis Drake, Sir John Hawkins

- The local workforce. During Peter Buck’s association with Chatham Dockyard, it was primarily a royal naval mooring and maintenance / refit base. The location being chosen because of the expanse of mud at low tide. This enabled ships to be embedded in the mud whilst the hulls were worked upon. They would then refloat when the tide came in. This is known as ‘graving’. This work required a workforce of skilled tradesmen. They could have included Matthew Baker, master shipwright, who supervised work at Chatham Dockyard and Phineas Pett, son of master shipwright Peter Pett. Phineas was appointed to the keepership/storehouse in 1599. He went on to become a master shipwright himself.

- Local landowners whose land may be needed for the operation and extension of the dockyard. ReinoldBaker was Lord of the Manor of Chatham in the late 16th century. As Lord of the Manor, he had control of marshland, river frontage, wharf rights, and rents and tenures. This mattered as the dockyard was not fully owned by the Crown at this time. Other key landowners could have also included John Callys, Thomas Wynall, William Mills, Thomas Morton, Thomas Short, and Thomas Derkyn, who between them provided land for mast ponds, sail-drying, and pitch and tar storage.

- Civic Authorities – The Mayor of Rochester and their office. Apart from any possible regulatory issues, the Mayor of Rochester had control of land bequeathed by Richard Watts to meet the needs of the poor and poor travellers. The local MP would have been an important person for Peter Buck to court. William Lewin MP., may have been particularly important as he was also, around this time, the Diocese Chancellor.

- Charitable bodies – Richard Watts Charity (1579), and the Rochester Bridge Wardens (1576). Peter Buck was associated with both organisations. The Watts Charity was established under the will of Richard Watts in 1579. It provided for six poor travellers and the poor in the neighbourhood. The charity was managed by the Mayor of Rochester, along with the Dean & Chapter and the Bridge Wardens. Its day-to-day operations were overseen by a Provider – a position held by Peter Buck in 1608. One can assume that Peter Buck would have socialised at Christmas with men associated with the running of these charities.

- Ecclesiastical Authorities. Building relationships with the Church would have been important for religious and secular reasons. Many senior members of the clergy associated with Rochester Cathedral may not have resided in Rochester at this time. The Dean and Chapter at Rochester would have been particularly important to the professional Peter Buck. The Church was responsible for the administration of the ecclesiastical courts. These were not marginal or “purely religious” bodies. They were everyday courts managing large parts of ordinary life. They involved borough elites, dockyard officers, craftsmen, and householders alike. It is therefore possible that Peter Buck’s office may have had to deal with the ecclesiastical court on matters crucial to land deals. It would also have been helpful to have access to lawyers who could be called upon.

- Local lawyers: Nicholas Morgan, lawyer and owner / resident of Restoration House from 1591 to 1610. There is no known link between Morgan and Buck, but being neighbours of similar social status, and both owning notable houses in Rochester, it seems possible they could have socialised at Christmas.

New Years Day (1 January)

This was the Tudor’s gift day.

Formal gift-giving was reserved for the first day of the year. Gifts would have been presented to Peter Buck as head of the household. He, in turn, would have presented gifts to other notables in the community – such as the clergy and the mayor – and people in his business network.

Gifts could have included money – often presented in a glove – and fine embroidered items. I suspect that, though his association with the dockyard, Peter Buck may have had access to many fine and exotic gifts imported from overseas.

Twelfth Night (5 January) Epiphany

This was the climax of Christmas, celebrating the arrival of the Magi.

In the aristocratic households, this could include the appointment of a ‘Lord of Misrule’. In lesser households, a ‘King of the Bean’ and ‘Queen of the Pea’ could be appointed for the day. They were chosen at random. A spiced fruit cake would have a pea and a bean baked in. Whoever received the slice with the bean or pea became the king or the queen.

This could be a community or household celebration.

After the 12th Night, the decorations came down, and normal work resumed. To continue the frivolities was considered to be bad luck.

—————————

Family Gaining Social Acceptance?

From what we know of Peter Buck and his immediate descendants, he managed his career and social progression well. He was promoted, around 1596, from ‘Clerk of the Cheque’ to being ‘Clerk of the Ships’. This was a senior post on the Navy Board. In 1603, he apparently hosted King James I. During this visit, he was apparently knighted for services to the Navy. In 1606, he hosted King to Denmark at Eastgate House.

A transcript of the accounts of the Richard Watts’ charity details payments to Peter Buck for being the “Provider” of the charity in 1608.

A compilation of people who held the position of a bridge warden lists Peter Bucke (sic) as being a Justice of the Peace. The listing also states that he served as a junior warden in 1604 and 1611, and as a senior warden in 1619. Holding this position suggests Peter Buck had achieved social acceptance at Rochester and in Kent.

Becoming a Bridge Warden at this time would have been significant. Becoming one was very much joining what could be regarded as a ‘closed shop’. Many Wardens and Assistants were related by marriage. Of the 100 bridge wardens elected between 1576 and 1660, half came from just twenty families. Becoming a warden was tantamount to joining the county’s gentry, who filled many major civic roles in the county. (Traffic and Politics. The Construction and Management of Rochester Bridge AD43-1993.)

One has to be cautious with websites stating that Peter Buck was once a Mayor of Rochester. He is not listed on comprehensive lists of mayors. There was, though, a P. Burke listed in 1593. This could be a misspelling of Buck(e), but it could also be another person.

I’m not suggesting that it was through his hosting of Christmas that Peter Buck achieved success. But I do suggest that the Christmas holiday afforded him many opportunities to be recognised and to build relationships.

Geoff Ettridge aka Geoff Rambler

24 December 2025

For more about Eastgate House Rochester see the following blogs: