History is not just about dates and events. This ‘story’ of Richard Watts and his charity tells of the experiences of ordinary people who lived through the turbulent dates and events we learnt about at school. This history of Richard Watts and his charity is a peoples’ history.

I wonder how many charities set up by one person have survived over 400 years? Certainly the Cathedral and the Bridge wardens, here at Rochester, have been around longer but they are corporate bodies determined by statutes and defined purpose.

The Richard Watts charity has morphed over the centuries. It still serves those in need – so long as they live in ME1 or ME2. And through its investment properties it continues to shape parts of Medway.

I hope to show that the key to the success of Richard Watts and his charity has been flexibility, responsiveness and relevance.

Richard Watts – Story of the Businessman

Let’s start with the Man – Richard Watts – who through is Will established the Six Poor Travellers’ House on Rochester High Street, and laid the foundations for the charity that serves us today.

Although referred to as the Traveller’s House it has been so much more than that. It was first and remained so, an almshouse with the inmates providing the welcome to the travellers. To this was added comfortable bedrooms for the travellers. It went on to provide accommodation for orphans, prisoners and sick soldiers. It provided workspace and a training school in the making of buttons. All this behind the facade of an anonymous looking house that has more than once been mistaken as a gentleman’s high street residence.

We know little of the Man but no man is an island. We live a life as much determined by the environment in which we live as our genes.

Much of which that has been written about Richard Watts’ background is speculative or perhaps invented. I’m not sure what led Edwin Harris in his history or Richard Watts or Rochester in the time of the Tudors (1903) to say that Richard Watts was with Bishop John Fisher when he was held in the Tower of London. (There is much in Harris’s book that needs to be treated with caution.)

Nevertheless I’m going to join the ‘club of speculators’ – but hopefully offering a reasonable basis for my speculations. I do though wonder if Richard Watts had been a traveller to have specified so much comfort for travellers – provision of money for food, a fire, good matrices and other furniture for their comfort.

To have survived let alone thrived in the Tudor period must have required a good network of contacts, fluid opinions and the ability to say the right things to the right people, or perhaps more importantly not saying the wrong things to the wrong people.

Today we would say such a person had a high EQ – Emotional Quotient.

During his lifetime Richard Watts lived under the rule of:

– Henry who set up a new church – but had Catholic leanings

– Edward and his minders – were fervent Protestants

– Mary who was firmly Catholic and vengeful and

– Elizabeth a Protestant but pragmatically tolerant when it came to private worship.

The waxing and waning of religious doctrines increased or reduced the likelihood of an invasion. This led to Edward and later Elizabeth l investing in the Navy and making Chatham their principal dockyard. A fleet located in the River Medway would have been well placed to intercept any invading fleet heading along the Thames to London. This decision benefited Richard Watts and led to his recognition by Edward who awarded him with a Coat of Arms, and Elizabeth regarding him a well-beloved subject.

How Richard Watts made his Money

So how did he make his money? Perhaps, as it is today, it’s who you know that can make a difference. A business man not so long ago when was asked how he was so lucky in business, reply that he had found that the more people he met, the luckier he became. Could this have been Richard Watts’ secret?

For Richard Watts to have married into the landed Somer family around 1530, he must have had wealth, status or have been well connected. By the late 1540s he was working on provisioning the Navy. He was specifically responsibility for supplying the ships at Rochester where he set up a new depot. This is what probably led to him being provided with the Coat of Arms.

This work provided many opportunities to ‘do deals’. The Admiralty gave an amount to the Victualler for the service. The Victualler then purchased what was needed – and kept the change. I’m not saying Richard Watts acted in a criminal way but just think of the opportunities there was to do deals and win favours! An opportunity that the roguish John Hawkins later availed himself of.

Richard Watts was later employed by Elizabeth 1 to oversee the building or Upnor Castle. He also took various positions such as with the cathedral and the Bridge Wardens, that came with a stipend. All providing opportunities and connections.

The Investments Made

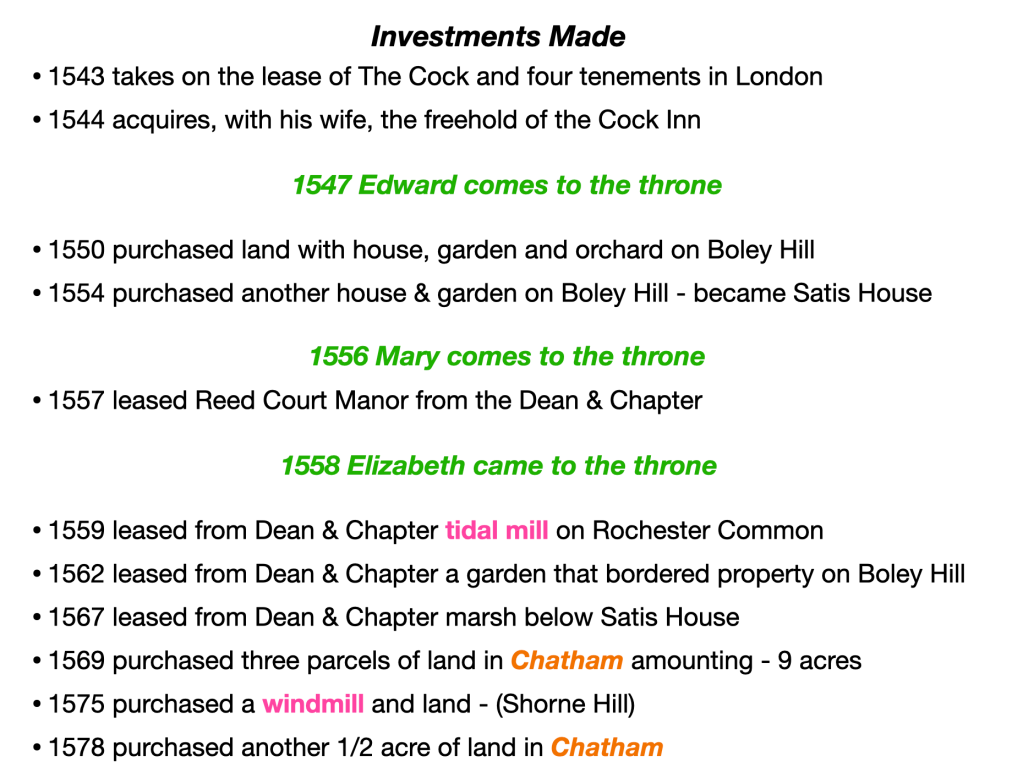

By the 1540s Richard Watts was clearly on his way up as he started acquiring a property portfolio – some jointly with his wife, Marian nee Somer.

His business and personal acquisitions really took off when Elizabeth came to the throne in 1558. Clearly he would have been more established by then but was there more confidence in the economy? After the turbulence of Henry’s reign the country was run by regents for a ‘boy king’ followed by Mary who was intent on returning the country to the Catholic Church. As an aside, to give a sense of the time, three people were executed at Rochester by burning – one in 1555, and two in 1556. They died not just for their beliefs but for remaining true to the faith/ policy of the previous reign; circumstances that may not have been conducive to doing business or taking risks at this time.

It is worth mentioning here that Tudor business tended to be undertaken on ‘credit’ with cash being invested in property – people back then would value a business man’s worth based on what he owned, rather than earned. Cash was therefore quickly turned into assets.

Looking at the portfolio listed on the slide I think there are two significant types of property such he was purchasing strategically not opportunistically – highlighted in colour in the above slide.

Firstly was he acquiring mills. Was this to enable him to profit from the milling of the flour that he then sold to the Navy? He was also buying land between Chatham and Rochester. Was this because he was anticipating the expansion of the dockyard being in the direction of Rochester?

This painting from the 17th century would give some credence to this possibility when overlaid with the area in which Richard Watts purchased land – overlaid in pink. The charity still owns land in the vacinity of Argos (store now closed) and the B&M store.

Later in the 19th century when the authorities were considering the charities development plan it became clear that the land Richard Watts had purchased went right down to the waterfront.

As we know the Stuarts developed the dockyard in the opposite direction. The land though still had income potential as Chatham began to expand, trade built up and there were more mouths to feed.

Having considered how he could have made money and how he used it – it’s time to take a look at what might have been behind his Will.

Richard Watts’ Will

Key provisions:

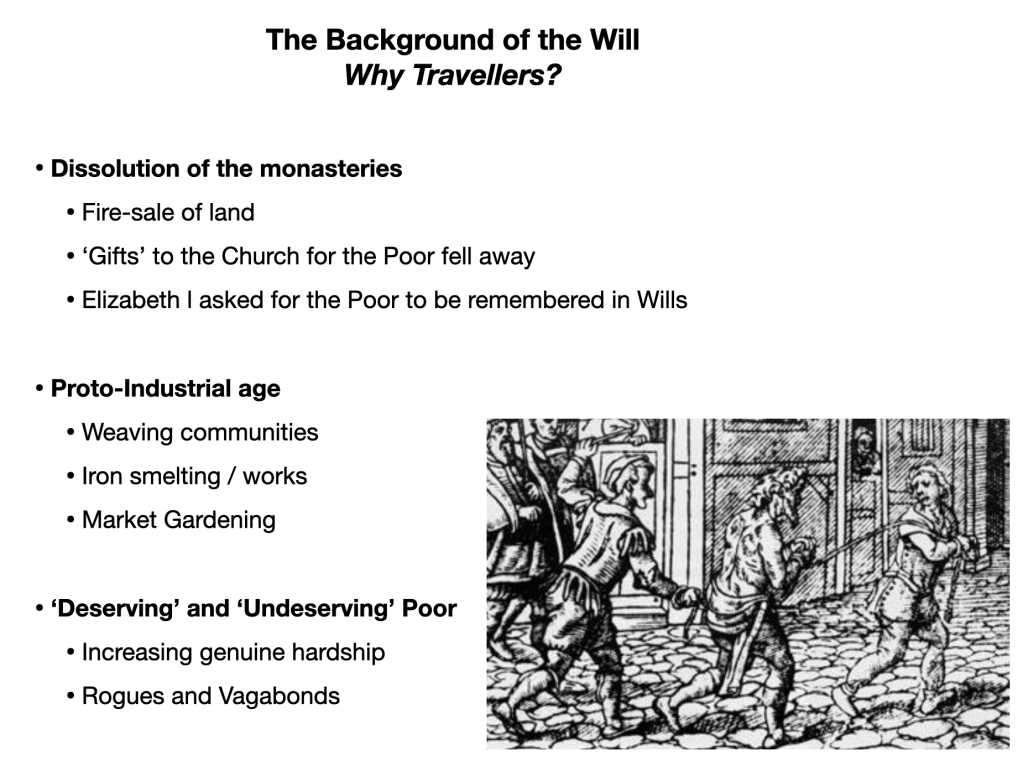

By the time Elizabeth l came to the throne it was increasingly accepted that there were many unemployed because there was no work. Also her father by dissolving the monasteries had effectively removed the health, welfare and education system from the country. He had also criticised the Church to the extent people were not giving so much so much money to it to assist the poor. To tackle the problem parishes were to purchase material to provide work for the able-bodied poor. Elizabeth l also wrote to the worthies asking them to remember the poor in their wills. It seems that Richard Watts heeded this call.

But why travellers?

I wonder if Richard Watts had had experiences that made him empathic to the needs of travellers – but I don’t know. Equally it could have been a way to make a small bequeath go further as to help all in need would have required enormous amount of money.

Travellers, like today, were regarded with suspicion. Amongst their numbers would have been criminals, desperate individuals and people carrying diseases.

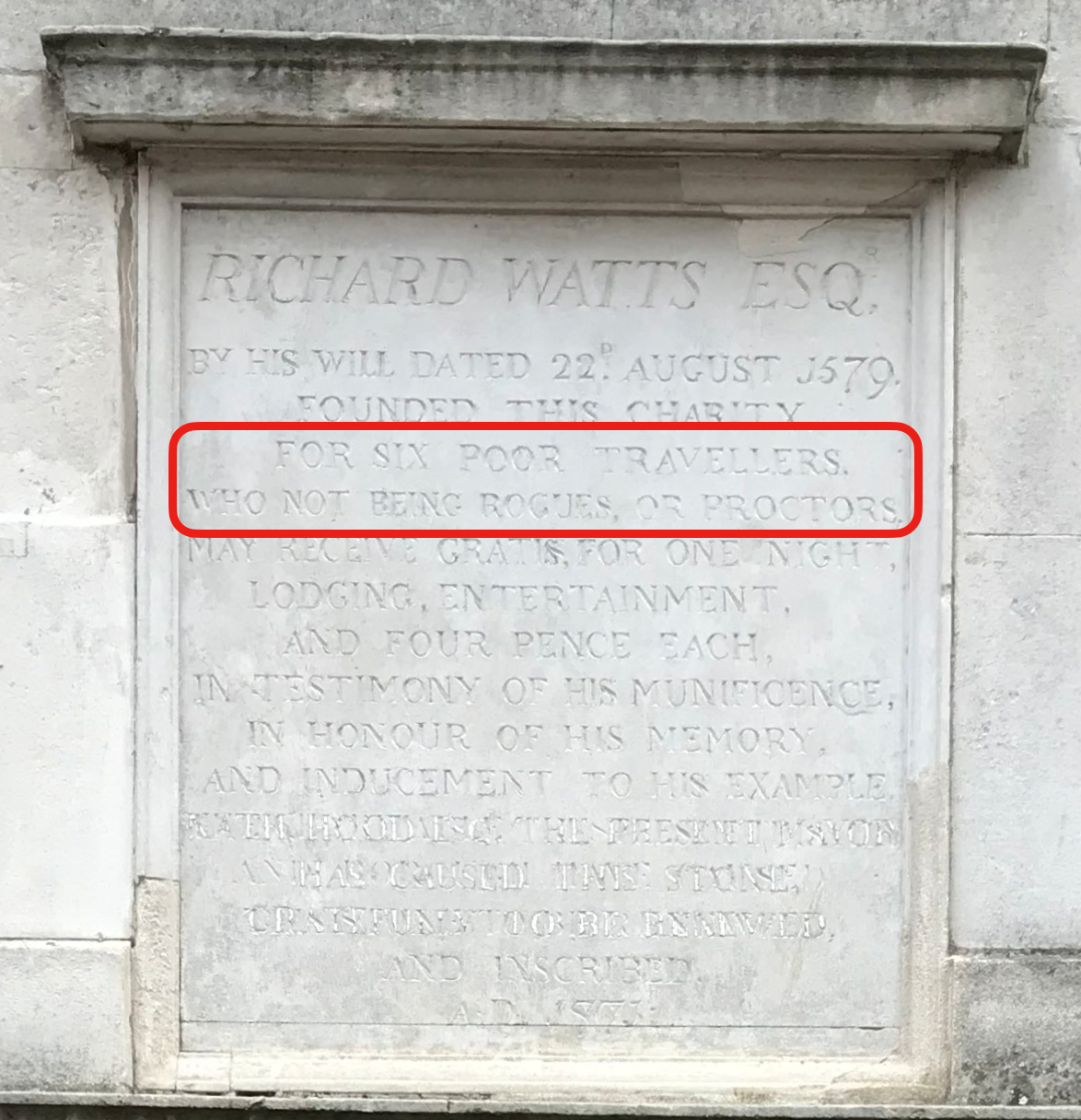

Knowing this Richard Watts may have excluded “Rouges & Proctors” as a way to make his Will more palatable. By his position in the community and from his house that overlooked the medieval bridge, he would have been aware of the large number of genuine people coming to Kent in search of work. At this time Kent was, if you like, the industrial south.

During the 16th century thousands entered Kent from continental Europe to avoid civil wars and escape religious persecution. People from the Low Countries and France brought with them skills and resources that stimulated the weaving industry as well as the smelting and casting of iron. Although farming was still on a domestic scale flemish people established market gardens that provided for London. There was therefore many ‘employment opportunities’ in Kent that could have drawn travellers.

If I’m right about the extent of the need why only provide for six? Perhaps it was because he was asset rich / cash poor? Perhaps it was because the income expected from the land that he gave to the Mayor to fund his charity was insufficient to provide for any more. If I’m right in my supposition the value was more its potential – but only if the dockyard grew towards Rochester.

Much of how the house went on to be used was not and perhaps could not have been, envisaged in the 1570s when Richard Watts was contemplating his will.

I find it hard to associate what we see today of the house – that is not that much different from the outside to what would have been seen from the 1770s – with its history.

There is though evidence of its earlier life – like the upstairs window now hidden by the Visitors’ Information Centre – but still visible from inside the house.

To convert the house to accommodation travellers would have been considerable. Chimneys in the 1570s in domestic properties would have been rare, but essential if a property was to be two stories high. This could suggest that Richard Watts did not have the funds to extend the footprint of the almshouse or acquire another site. Further major work on the almshouse though had to await the remarriage of Richard Watts’s widow Marian in 1593 as Richard Watts’ had stipulated that his estate remained with her until her death or remarriage. It is also worthy of note that Marian and her new husband, Thomas Pagitt, contributed 100 marks to the conversion of the almshouse. (A mark was the equivalent of 2/3rd of a pound; they therefore contributed around £17,000 at today’s value.)

By the start of the 1600’s work started apace. In 1608/09 a carpenter was paid to assemble three looms, and timber, nails. lathes and prigs, lime and hair were purchased (and a lot more). Carpenters were employed for twelve days to work on the almshouse and the stairs. Rubble was removed and Goodwife Forman and the “wife of the house” were paid to clear the cellar. But by 1615 an additional use was envisaged for the house – on top of providing accommodation for the ‘impotent poor’ and travellers, it become a children’s home; and later still it included a House of Correction to ‘correct’ the idle but able poor.

Children’s’ Home

The colour of the uniform was described in the accounts as being Cambridge Blue. I may be a coincidence but I’ve notices that its not uncommon to find blue in the colour of clothing provided by the parish.

Why it was decided to accommodate children in the house is unknown. However in the years leading up to 1615 Rochester had experienced several outbreaks of the plague. Was this therefore a pragmatic solution to a significant orphan problem? The house could provide accommodation and the bequest of Richard Watts could be used to help the children acquire an apprenticeship. Six girls and 10 boys were accommodated in the house. Beds and stools were constructed and partitions & doors were installed.

Girls stayed until they were 16 and boys 18. This may have been because girls were likely to move into domestic service and became part of their employers household.

Based on the charity’s accounts the children were well cared for. In 1625 payments were shown for the placing out of children. Was this because the numbers were greater than could be provided for in the house? A Ye olde fostering scheme? For those signed up for an apprenticeship appropriate clothing was provided for the trade to be followed. By serving an apprenticeship and becoming a member of a trade body reduced the likelihood of that person at sometime in the future needing to turn to the Parish for support.

In 1633/34 an inmate widow Alice Saxbie was paid £5 and supplied with coal to teach children to make buttons. It’s also worth noting that she was loaned £40 to buy material for button making. Could this have been a business loan with her and the children keeping profits. Click here for more about the children’s home.

Support for sick and invalid soldiers

Soldiers in the 17th century were ‘expendable’ – something that was not going to change much until the late 19th century. An injured solider would be discharged and left to their own devices.

The accounts show that the charity was sensitive to the needs of destitute and sick soldiers – even if they broke windows as mentioned in the accounts. In 1623 Daneill Waldern, keeper of the almshouse, was paid for taking in two poor soldiers for three weeks and one for one week as he died. A poor woman was paid 12d to lay this sad soul out. 16d was paid to Thomas White to bury him, and 16d was paid to four men to carry the solider to his grave.

John Hawkins recognised the problem of invalided sailors and established the Chatham Chest in 1590, at Chatham, that sailors paid into as a welfare fund.

House of Correction – 1653 – ?? and 1711 – 1793

1609 – payment made to the Dolphin Inn to ‘hold’ five soldiers accused of being

1653 – opened House of Correction – where was the earlier one?

1657 – Alice Towers – Political abuse of power?

1711 – 1793: reopened – lewd & disorderly conduct of the inhabitants

It was not until the 19th century that prisons were built for the sole purpose of housing criminals.

Before then make-do arrangements had to be made – although I’m not sure why Richard Watts money was used to ‘accommodate’ “pirates” at the Dolphin Inn.

Under the 1601 Poor Law Act parishes were expected to set up Houses of Correction – to ‘correct’ those who could but would not work so I’m not sure whether there was anything in Rochester before the cellar of the travellers house was converted in the 1650s.

The images in the above slide are of parts of the travellers house were not open to the public – but the door is still in place. I’m not so sure about the story that the makings on the floor show where stocks and a whipping post were located as these would be punishments of public humiliation. Could they have been where domestic equipment were located?

An Alice Towers was locked up here in 1657 because she left her job as a barmaid before her contract was up. The fact that she received compensation for wrongful imprisonment suggests the Mayor who ordered her lock-up had enemies prepared to cover her legal expenses. At some time the jail was closed but reopened in 1711 because of the lewd and disorderly conduct of the inhabitants of Rochester. It seems the jail may have been run separately to the house as the Mayor had to get an eviction order when the jail closed in order to get the gaoler out! Click here for more about the House of Correction.

A Family Home

From 1829 the Travellers House was also the home of John and Susanna Cacket who had been appointed as the Master and Matron of the house. They had a large family. There is no evidence that Charles Dickens modelled his “Crotchet family on the Cackets but there are similarities in size and surname.

At the time of their appointment they would have been aged about 45 and 35 respectively. Here they raised their family. The 1841 census shows there were eight Cackets and three travellers in residence on census night.

By 1851 three of the girls listed in 1841 were not in residence. John and his sons were listed as Printer/Compositors. Of the six “inmates” all apart from one appears to have had a trade requiring specific skills.

In his Seven Poor Travellers written in 1854, Charles Dickens accuses the matron of engineering a situation that would have pushed the travellers out of the house so she and her daughters could enjoy the whole house. It’s very unlikely that a matron back then would have had that type of influence. This accusation caused her great hurt and outrage in parts of the press who went on the praise the way that Susanna ran the house. Apparently she was awarded £10 damages by Dickens to avoid a Court case.

Dickens visited the house in May 1854 in the knowledge that the Government had sent in the Charity Commission to look into the proper running of the charity.

This is not the place to go into the detail of national politics but by the end of the 18th century there were growing demands for more representative national and local government.

Here in Medway the poor faced dire conditions with the ending of the war with Napoleon. Jobs had been lost to mechanisation of farming that occurred during the war; there had been a mass demobilisation of people serving in the military when the war ended, and the cost of bread was being kept unnecessarily high by the ‘protective’ Corn Laws. A combination of these factors increased the demands on the parishes for alms.

These circumstances plus the knowledge that the income being received by Richard Watts charity exceeded its requirements, probably provided the impetus for Chatham to make a claim on the income received by the charity. At the time of Richard Watts’ Will there would have been no delineation between Rochester and Chatham. The claim was subsequently resolved by including Chatham Intra as a beneficiary area.

These were not just local problems. Internationally there were revolutions or threat of, by people wanting more say in the running of their country. What made the risk more likely was that the working and middle classes were joining forces. In order to avert calls for more radical reforms in England the Government passed the Reform Act 1832. This created a more representative parliament and perhaps more significantly, gave the vote to members of the middle classes. This cleaved any possible coalition between workers and the middling classes and demised the likelihood of a rebellion. This reform was later followed by the Municipal Reform Act in 1835. This Act tackled the issues of accountability in local government, and consequently had a significant impact on the running of the Richard Watts charity.

The Charity is Reformed

The significance of this small plaque on the front of the traveller’s house could easily be missed.

Under Richard Watts Will a collective of the Mayor, Citizens of Rochester and the Bridge Wardens managed the charity. In effect it was the Mayor and what I shall call ‘his mates’ who decided how the charity’s income was spent. When the income exceeded what was required to provide for the travellers he decided that it could be used to help the poor by subsidising – not supplementing – the Poor Rate. I emphasise subsidising not supplementing. This meant it was those who paid the Poor Rate who benefited, with some parish inhabitants such as those in St Nicholas not paying any Poor Rates. This in turn helped ensure the Mayor’s re-election as it was those who would have been liable to pay the Poor Rate who had the vote. This arrangment greatly trobled the radical liberals of Rochester.

The 1835 Act also required the Council to establish trustees who would manage the Charity. This plaque shows they took up their responsibilities in 1836.

Sadly the new trustees – mostly liberal-radicals – were no more ethical than the mayor as they favoured their own with contracts. The management of the charity became a major issue in the local elections of 1848, leading to the Charity Commissioners taking it over in 1853.

The Charity Commissioners Intervene

At Rochester the running of the Richard Watts charity was not alone in being of concern. Robert Whiston, a headmaster of the Kings School in the 1840s had raised concerns about how the Dean & Chapter were administering the payments due to the scholars of the school. This matter quickly reached National prominence. Rochester was not necessarily a ‘bad place’ – there was a national issue pertaining to ancient charities where circumstances that had led to them being set up had significantly changed. Anthony Trollope’s Warden was based on this theme.

The Charity Commissioners arrived in Rochester in April 1854 to look at the running of the charity. Dickens always on the lookout for some contemporaneous news to include in his stories, visited in the house in May of that year to collect material for what would become his next Christmas story – The Seven Poor Travellers.

If you’re interested read the first chapter as Dickens’ interpretation of the facts. Ignore the aggrandizement he gave himself – the matron said he didn’t meet any travellers when he visited, during the day, let alone provide them with a Christmas meal – and why would he in May?

They Commissioners consulted widely to devise a new scheme for the Charity. Although they decided against increasing the number of travellers to be provided for, they upped the quality of service they would receive. They also made significant decisions on the use of the charity’s assets to broaden the provision made for the local poor.

The Commissioners consulted widely and:

- Decided against against increasing the number of places

- New trustees to act for the Charity not the Municipality

- A master and matron to be appointed – £25/ann (£2,600)

- Travellers to be given a hot meal in the evening

- Travellers to be given 4d on their departure

- New almshouse for 10 poor men and 10 poor women

- Five of the women to be over 35 to act as nurses – to be paid £20/ann

- St Bartholomew’s hospital’s (Rochester) building fund to receive £4,000 then £1,000 per ann.

- Support to be given to up to five poor boys/girls in an apprenticeship.

- £2,000 to be spent on erecting baths / washhouse + £200 / ann towards running costs

Under the new scheme totally independent trustees were to be appointed – who were is act entirely in the interests of the charity and its beneficiaries. They were also to be accountable to the Charity Commission not local politicians.

The Charity Commissioners directed that a new residential service was provided for older infirm people, and funds were to be provided to go towards the building and running of St Bartholomew’s Hospital – a service that would benefit the poor as the more wealthy were treated at home.

Perhaps the most innovative decision was the setting up of what we would recognise today as a Community Nursing Serve. The five nurses not only supported residents of the almshouse they provided for the sick living in the locality, and women whilst they were ‘laying-in’ after giving birth.

The nurses became a valuable community resource – an early district nursing service if you like. They became sufficiently competent to provide additional nursing support to the Strood VAD hospital during WW1. The service was finally taken over by KCC as part of the NHS provision around 1950.

The Trustees were also responsible for ensuring that the charity investments were managed in a way that benefited the charity’s beneficiaries – not their ‘mates’. This had enormous impact on Medway. As I highlighted earlier much of the investment properties held by the charity lay between Chatham and Rochester.

The new trustees did not waste time in getting started with their new responsibilities. The hospital cost £7,000 to build with £4,000 provided by the Watts Charity. Income, some of which was provided by the Richard Watts Charity, was insufficient to support 80 beds – so 30 of were ‘sold’ to the MOD and the Admiralty as Locked Wards that were used to lock up women thought to have VD. Click here for more about the Locked Wards of St Barts.

Improving Chatham

It appears to me that the charity’s trustees – prior to those appointed by the Charity Commission did little to manage the assets of the charity – apart from perhaps collecting the rent.

As with all businesses a charity needs to sustain an income to remain functional. Failure to invest in the maintenance of property will led to a depreciation in income.

The new trustees inherited areas that were little more than slums. To quote a letter in the press in 1861 writing about the area owned by the Richard Watts Charity, described it as – a plague-spot and disgrace to the town.

Another charity with a significant land-holding between Rochester and Chatham were the trustees of St Bartholomew’s – and they needed income to run their new hospital.

With the creation of a new hospital, the two newly appointed teams of trustees worked together on improving the parts of Chatham they owned and thereby maximising their income. An advocate for what I will call the Chatham Improvement Plan said it would deliver improvements to the town that has not been seen for centuries – an outcome that would have been welcomed by the Local Health Board for Chatham that was set up in 1849.

The area under the pink in the image below covers the 1860 Watt’s Improvement Zone. The new road proposed linking Sun Pier to Globe Lane became Medway Street. This zone is now part of the new Chatham Waterfront Development. (The land belonging to the Richard Watts Charity was compulsory purchased by the Council to take forward the current development.)

Opposition to the 1860 improvement scheme seems to have been about the loss of the existing public quay as Watts owned the foreshore. The opponents argument was the economy of Rochester was damaged with the loss of a quay that had to be given up for the construction of the new cast iron bridge.

Arguments in favour of the scheme was that the current quay was an underused mud flat and that Watts was proposing a larger one that went down to the low water level.

Advocates of the improvement scheme rather hoped public baths would be included but as we know only one bath was established and that was at Rochester.

House Improvements

The travellers had to wait until the 1930s before they had mod cons.

The area encircled by the red – toilet, wash basins and bath – located beyond the dinning room – I think disappeared when the house was converted into a museum around 1977.

The house that took in its first travellers in 1588 was closed in June 1940 on the instructions of the chief constable and did not reopen to travellers after the war. It even had stayed open during smallpox epidemics with a doctor being appointed to review a traveller’s health before allowing admission. After WW2 the house had a period providing accommodation to couples before being closed and turned into a museum.

Today

A combination of the investments made by Richard Watts and how the post 1855 trustees have managed the charity’s resources, ensures that the charity is in as strong position to continue to support those in need who live in the postal areas of ME1 and ME2, and to support young people in pursuing their education. Details of the charity’s income, that can be found on the internet, illustrates how the charity has successfully moved with the times.

Today the charity awards grants, in agreement with the trustees, as well as providing:

- Home help service

- Lawn cutting service

- Funding for Medway Telecare

- Essential household equipment

- Grants for school uniform

- Apprenticeship grants

- Support for those in education and training

The Richard Watts Charity also provides grants to other organisations needing the needs of those in need such as the Medway Food Bank and Caring Hands.

So what of the future?

Hopefully I’ve shown how a charity set up in 1579 has remained as relevant today as it was back then.

During the 400 plus years it has morphed into what was required at the time, and is perhaps more viable today than back then – with an income of over £1m per year since 2010.

The charity indirectly or directly has helped shape the politics of the area, and the way charities are run nationally. It has and still does benefit individuals in need as well as, along with other land-owning charities, helped shape Chatham and Chatham Intra.

Many walk past the Travellers House – perhaps thinking it was the residence of a wealthy family – but just think about who has crossed it threshold seeking help and refuge.

I am certain as anyone can be that the Richard Watts Charity will continue meeting local needs for the foreseeable future – but I’m not certain about the future of the house. The museum did not open this season. The only explanation is that it’s closed for “maintenance work … until further notice” – of which the only visible evidence is the boarding up of the lower front windows.

As confident as I’m about the future of the charity I’m certain few involved in managing the charity today will be aware of the full story that I’ve just partially told. This house and what it’s done, provides a lens through which to view Rochester’s living history.

If it were – and I’m not saying I know anything because I don’t – be turned into an Air B&B how wrong would that be for a property that has moved with the times, and a charity that uses its income to benefit local people?

The house has a marvellous story to tell – which to my mind has never been well told – but it’s far from accessible and perhaps could never be adapted to make it so.

I’m not certain what the house should become – but I’m inclined to feel that its life should continue as part of the charity and the community, and that its story should not be ended by being just memorialised as a museum.

What I am sure of is that there is potential for a very lively debate between those who need to maximise income for those in need, those who want to preserve the past, and those who feel it would be wrong to ‘nip the top out’ of a living and evolving charity.

Geoff Ettridge

Presentation that was to be given to the City of Rochester Society – 5 September 2023