It is easy to fall into the trap of thinking past Christmas’s were as shown to Ebenezer Scrooge by the ghost of ‘Christmas Present’ in Dickens’s Christmas Carol (1843). But this visitation was imaginary as the ghost visited Scrooge the night before Christmas Day so was showing him what could be, not what will be. Although Charles Dickens is credited with ‘inventing Christmas’ it is clear from reports on the harsh lives of people accommodated in workhouses that there was recognition that Christmas should be a joyous time celebrated with family sitting around a fire and enjoying good food and luxuries.

Despite the extensive use of snow scenes on Christmas cards it is a very time ago that one could reliably expect a ‘White Christmas’ in Kent. In 1869 a journalist wrote that he had thought that the image of an “old fashion Christmas of bitter wintery weather” was out of date. But on Christmas Day that year the people of Medway woke to a “pretty thick mantle of snow”. The snow continued to fall throughout the day, and the thermometer fell a few degrees below freezing (Chatham News, 1 Jan. 1870).

I’m not wanting to destroy the sentimental view of Christmas but past Christmases have been hard but they have also brought the best out of many. The following is drawn from a miscellany of notes I’ve made whilst researching for my various blogs and tours. Although there was bad news it is clear that people across Medway made extensive efforts to create and into enter into the festive spirit – despite many adversities ….. many not too dissimilar to today?

Text in green are my own interjections

Children and the 1834 New (Punitive) Poor Law

Perhaps more so today Christmas is for the children but in the past there was the empathetic view that the children of the poor should not be deprived of the seasonal pleasures because of the circumstances or mistakes of their parents. This though was not always shared by those charged with the responsibility for caring for children who had entered the workhouse.

The purpose of the New Poor Law was to reduce the burden on parishes who needed to provide for those unable to find work or afford to live on the wages they could earn. (Mechanisation introduced during the Napoleonic War had reduced the need for agricultural labour, and the Corn Laws kept the price of grain high and in turn the price of bread. The increasing numbers turning to the parish for help pushed up the Poor Tax which in turn led to employers needing to lay off more workers to pay the tax.)

The new law removed the provision of ‘out-relief’ and required all those seeking support from the parish to enter a workhouse. These separated families and only provided the most basic of life-sustaining food; the intention was to deter people from seeking support from the parish.

Medway had a number of workhouses including Chatham, referred to as the Medway Workhouse, and workhouses at Rochester and in Strood (Gun Lane.) There was also one at Hoo (opened 1836) – but more of that appalling place later.

The harshness of the workhouse regimes was largely set centrally by the Poor Law Commissioners. This included allowing corporal punishment and the setting a minimalist diet that rotated throughout the year – regardless of any festival – e.g:

Breakfast 6oz bread, 1.5oz of cheese. Dinner 1.5pt soup. Supper 6oz bread, 2oz of Cheese.

Many members of the public took exception to the way those who were unable to work were treated in the workhouses. In 1835 “benevolent individuals” of Medway wrote to the Poor Law Commissioners about the unwillingness of the Guardians of the “Poor Law Bastile” at Chatham to increase the dietary allowance for inmates at Christmas. With no movement on the part of the Commissioners fundraising was undertaken to provide extras at Christmas.

Medway Union – also referred to as the “Chatham Bastile” (West Kent Guardian, 6 Jan 1838). (This would have been the workhouse located near what is now known as The Brook, Chatham. The workhouse located in Magpie Hall Road / site of the old All Saints Hospital opened around 1859.)

In 1837 it was reported that donations (subscriptions) were collected for the “purpose of providing roast beef and plum pudding for the paupers in the workhouses belonging to the Medway Union” (Maidstone Journal, 12 Dec. 1837). The journalist commented that he could not see why people compelled by poverty or infirmity of age, and needing to seek shelter in a workhouse, should be prevented from tasting such things as roast beef and plum pudding at the merry time of Christmas. Equally the writer could not see why children who through no fault of their own should be refused a small portion of the good things of the world while thousands of their fellow creatures sitting around a fire enjoy the luxuries of life.

At Christmas 1839 it was reported that the 191 boys and girls accommodated in the Medway Union workhouse at St. Nicholas, Rochester, were served with roast beef and plum pudding – all paid for by public subscription.

By 1855 – and some 20 years after the enactment of the Poor Law – the public’s generosity had increased. A Christmas Treat Fund had been step up – donations to which enabled the children of the Medway Union to enjoy, on Christmas Eve, Chelsea buns and bountiful dessert, and each to a pair of warm gloves. In addition the Medway Guardians provided a “liberal supply of beef and plum pudding” on Christmas Day (Maidstone Journal, 2 Jan.1855).

By 1863 there seems to have been a significant change of heart on the part of those responsible for the running of the Medway Union.

“Most our readers would no less surprised than delighted if they could yesterday have seen the chapel and’ dining-hall of the ’Medway Union decorated for Christmas—the adornments were more than pleasing, they were handsome and striking. Wreaths and bunches of evergreens, artificial flowers, inscriptions and other ornaments, covered the walls, rafters, and the gas-branches; producing a really beautiful effect. (One has to suspect that a lot of credit needed to go to the master and matron as over the entrances to the decorated rooms were the words“ God bless the master and matron, and all our patrons.” (Chatham News, 26 December 1863).

Arranging for a Christmas in the Medway Union would have been a challenge. The 1881 census listed over 600 inmates.

Child Abuse in the Hoo Workhouse

The children of the Hoo Union in 1840 would probably have had a terrifying Christmas – and probably also at earlier Christmases as the union had only opened in 1836.

In December 1840 James Miles the master of the Hoo Union was interviewed by Rochester’s magistrates at the offices of Essell & Hayward on College Green. They had been made aware of the cruel and indecent beatings he had administered to children “of a tender age” who resided in the Union. Women who also resided in the workhouse – and would have been accommodated with the young children – were rightly fearful of the master so they had not spoken out. (Many references – London Evening Standard, 12 December 1840.)

Despite irrefutable evidence (not to be described here, but was provided in detail in the press) of the cruel punishment delivered by Miles the magistrates seemed unable to intervene as the ‘regulations’ laid down by the Poor Law Commissioners permitted the use of corporal punishment. They therefore allowed him to return to his duties. It’s hard to imagine that such a sadistic man would not have extracted reprisals or tried to intimidate witnesses. (A prosecution started in January 1841 but did not reach a hearing until March 1842. Miles was not charged with assault but the “scandalous and unjustified manner” he administered corporal punishment. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to six months imprisonment for the assault of two women – not the ‘abuse’ of the children as it was believed the evidence of a pauper child could not be trusted.)

(The Hoo Union was not alone in severely beating children – it was happening in schools across Medway, including the Maths School (e.g. West Kent Guardian, 8 Oct. 1836) and Kings (e.g. London Daily News, 22 Mar. 1850). In December 1863 a school master at the Medway Union was fined £1 with 12s costs for “severely and unnecessarily flogging” a boy of the school (Dover Express, 26 December).

Six Poor Travellers – High Street Rochester

I am sure that the 19th century trustees of the Richard Watts Charity would have ensured the travellers who spent a Christmas night in the house would have received a good meal. However it wasn’t until the story of the possibly imagined feast, that Charles Dickens provided for the travellers in 1854, that travellers staying in the house started to have a 4-Star Christmas.

Following the publication of Dickens’s Christmas Story The Seven Poor Travellers (1854) in which he cast himself as the seventh, he appears to have done nothing to correct the view that he had paid for his fellow travellers to have a sumptuous Christmas meal.

Dickens had indeed visited the traveller’s house but it was in May 1854 and not at Christmas. Further the matron told various reporters over the years that Dickens did not provide a meal for the travellers -“there had been no supper, no wassail, no hot coffee in the morning, no meeting at all between Dickens and the travellers at Christmas, or at any time” (Maidstone Journal, 30 Dec.1873). Perhaps mischievously a landlord (possibly the Kings Head at Rochester) submitted a bill to Dickens for providing the alleged meal (Maidstone Journal, 9 Jan. 1855).

From the Seven Poor Travellers:

“I [CD] was possessed by the desire to treat the Travellers to a supper and a temperate glass of hot Wassail; …. It was settled that at nine o’clock that night a Turkey and a piece of Roast Beef should smoke upon the board; and that I, faint and unworthy minister for once of Master Richard Watts, should preside as the Christmas-supper host of the six Poor Travellers”.

At the appointed time Dickens wrote he processed from the inn to the Travellers’s House:

“Myself with the pitcher.

Ben with Beer.

Inattentive Boy with hot plates. Inattentive Boy with hot plates.

THE TURKEY.

Female carrying sauces to be heated on the spot.

THE BEEF.

Man with Tray on his head, containing Vegetables and Sundries.

Volunteer Hostler from Hotel, grinning,

And rendering no assistance.”

Despite the possible false nature of the story it did not stop newspapers repeating it over the years. As a consequence of Dickens’s association with the travellers house it received visitors and support from around the world – particularly at Christmas time.

For example – in 1892 it was reported that those lodging at the ‘rest’ on Christmas Eve received extra benefits to those which customarily fall to the lot of the travellers. This Christmas for instance “pipes, tobacco, pouches, mittens, papers etc., were sent from friends who having visited the Institution [had taken] a kindly interest in its welfare” (Folkestone Express, 28 Dec. 1892).

Hospitals

In 1863 the new St Bartholomew’s Hospital at Rochester opened – although not officially opened until December 1880 (East Kent Gazette, 11 December 1880). It was specifically opened for the poor – with the richer people being treated at home. It was reported that for Christmas 1869 each patient in the hospital had for their Christmas Day meal, half a pound of beef or pork with vegetables followed by one pound of plum pudding. (I can’t imagine patients in hospital today having such an appetite!)

Nursing staff in our local hospitals appear to have gone to extraordinary lengths over the years to ensure those who had to spend Christmas in hospital had a joyous time. This was never so more than during wartime.

The following describes some of the arrangements made in the local hospitals to celebrate Christmas 1914 – taken from Chatham, Rochester & Gillingham News, 2 Jan. 1915. All hospitals were dependent on gifts and donations from individuals, firms and organisations.

Christmas at Strood VAD Hospital. “Thanks to the energy of the Commandant, Mrs. Skinner and Dr. Skinner, and the aid of many kind and sympathetic friends in the neighbourhood, Christmas was most enjoyably celebrated by the British and Belgian wounded soldiers, and as many of the nursing staff as could attended, in the commodious and tastily decorated hall of the Cooperative Society [Frindsbury]. The decorations being the work of nurses and many of the patients”.

Christmas at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital. “The festive season at St. Bartholomew’s was a quite different matter compared with the past years, for under the same roof were 30 wounded British and Belgium soldiers, and all the other beds for civilians were full. The first event on Christmas Day was the singing of carols by the sisters and nurses, who, with lighted tapers, went from ward to ward, and when day broke each patient found the customary gift lying on his or her locker. There were no decorations except in the soldiers’ two wards where the patients had expressed a special wish to see some evergreen”.

Christmas at St. William’s Hospital. “Here the troublesome times were not allowed to shadow Christmas. There were few adult patients but approximately 50 children. The wards were charmingly and daintily decorated, a giant Christmas tree well laden with toys and stockings filled to over flowing. Nurses arranged games, there was a gramophone and other homemade amusements of infinite variety.” (St Williams was built to be an isolation hospital.)

St Williams Hospital

The efforts made by the nurses continued throughout the war. In 1916 the nurses of St. Bartholomew’s, Rochester, started Christmas Day at 5am by going from ward to ward singing carols. They had previously ensured all the wards were tastefully decorated but they had made a particular effort for the two wards at the hospital on which 58 wounded soldiers were being cared for (Kent Messenger, 30 Dec. 1916).

As to be expected for Christmas 1918 the Matron of St. Bartholomew’s hospital made a special effort to celebrate Christmas:

St. Bartholomew’s was particularly full. “So far as the pain and suffering would allow the patients had a very happy Christmas. The inmates it may be mentioned were few in the military wards, but on the civil side every bed was occupied and several emergencies were admitted during the day. The decorations were far more extensive than in previous years and in this respect Florence and Constance Wards call for special mention. In Florence, the male surgical ward, the nursing staff and patients had constructed a number of miniature aeroplanes and these with festive balloons formed the main feature in the centre of the ward. Over each bed was hung a tiny aeroplane and parachute, and when the whole were electrically illuminated in the evening the effect was an extremely pleasing one. The larger aeroplanes were not introduced into Constance ward, but the whole arrangement was an exceedingly delightful one. Christmas Day opened with carols by the staff who between 5am and 6am went from ward to ward singing. There were presents for all. There were many visitors throughout the day. Miss Pote Hunt, the matron, doesn’t remember such a day for visitors. According to a custom that she had initiated when she first came to the hospital, each patient was allowed a visitor to attend at his or her bedside. The day came to an appropriate conclusion at 7pm by the singing of the Doxology.” (Chatham Rochester & Gillingham News as well as the Observer, 28 Dec 1918.)Blog – Matron Honoured

During Second Word War the nurses, as they did during World War 1, made great efforts to bring festive spirit to the wards for Christmas. Although there was only seven patients in St William’s Hospital the nurses had decorated the diphtheria ward with yellow roses hung in arches, and they made paper chains and evergreen garlands to adorn the cubicles. On Christmas Day a traditional turkey dinner was served. Similar festivities occurred at St Bartholomew’s and the Royal Naval Hospital (now Medway Maritime). (Chatham News, 29 Dec. 1939).

Life Threatening Epidemics & Fire

This 2021 Christmas is only likely to be disrupted by Covid. In times past there were many more diseases in circulation – all being capable of delivering death and disability. Measles, Scarlet Fever, Diphtheria and even Smallpox could rip through Medway with devastating affect. Although vaccines were being developed the main defence against these diseases was as it is today – Avoidance, Isolation, Ventilation and Sanitisation. In December 1839 following the death of several children of invalids of Fort Pitt in the past fortnight from measles, the government was criticised for not “providing some other receptacle for poor invalids” (Kentish Mercury, 21 Dec. 1839). Blog: Medway Epidemics.

1918 saw the arrival of the deadly Spanish flu. It killed more people than who died in the war and the young were the most vulnerable. In December 1918 it was reported to Rochester Council that during the five weeks ending 23 November, that there had been 77 deaths from influenza – 46 in Strood and 31 on the Rochester side of the bridge (Chatham, Rochester & Gillingham Observer, 14 Dec. 1918). There was no vaccine but an experimental treatment involved giving plasma taken from someone who had survived the flu to someone who was ill with it. This treatment was tried in the early days of the fight against Covid 19. More on Rochester’s 1918 Flu epidemic Flu Blog.

The Risk of Fire

Before homes were connect to electricity, heating and lighting was largely provided by an open flame. Although not just a Christmas risk the dark cold days of December meant there were more flames in homes for longer. Clothes were hung in front of fires to dry, where they could catch fire, and there were frequent reports in the Decembers of the 19th century of oil lamps being knocked over. Most deaths associated with fire were of women whose ‘voluminous’ victorian fashion posed a particular danger; clothing could cause a lamp to be knocked over and the material of dresses could soak up the knocked-over burning oil, (e.g. West Kent Guardian, 31 Dec. 1842). The accident described in this report pre-dates the opening of St. Barts and the badly burnt woman was taken to the infirmary at the ‘old’ Medway workhouse where she died without the benefit of any pain relief.)

The Great War becomes real on the Home Front

War can bring the worse and the best out of people – particularly at Christmas. Medway – particularly Rochester – was one of the first places to experience war coming to our shore. Earlier wars involved sending men to fight overseas. As a consequence only secondhand reports of war were received. This all changed with WW1.

In August 1914, shortly after Britain entered the war, 60 disheveled refugees landed at Strood (Chatham, Rochester & Gillingham Observer, 29 Aug. 1914). (The Belgian refugees were quickly accommodated in and around Rochester.)

On Christmas Day 1914 at around 1pm when families in Cliffe were sitting down to their Christmas Dinner, they witnessed he first aerial battle that ever took place over British soil. On going outside they witnessed a German plane following the Thames towards London being pursued by a British pilot. The peace of the day was further disturbed by artillery fire when the German plane was on its return journey. Going outside was dangerous – not necessarily from bombs but shrapnel from our artillery shells (Chatham, Rochester & Gillingham News / Observer, 2 Jan. 1915). See blog for more detail). For more about this air raid see my blog

To ensure that refugee children and local children who had lost their father to the war received a Christmas gift, the Mayor of Rochester in December 1914 made an appeal for toys. (By mid December 1914 there were, in Rochester, 30 children under the age of 9, in 14 families, who had lost their father.) The mayor also requested cheap toys that could be given to the 40 to 50 children who were going to spend Christmas Day in St. Williams isolation hospital. (Chatham, Rochester & Gillingham News, 5 Dec. 1914). Cheap toys were requested as they would need to be destroyed when to child (hopefully) was discharged home, in order to prevent the spread of disease.

War and Workhouse Inmates

Despite a lessening of the hardships placed on those who had turned to the parish for help there were those who felt that residents of a workhouse should not receive any luxuries. This was clearly evident during WW1. There were those who believed – before conscription was introduced – that all abled bodied men in the workhouse should be serving in the military. There was also the issue of the food and luxuries that should be provided for the inmates at the time of shortages – but reports of the workhouse guardians did suggest that the proposed reductions may have been more punitive than necessary.

At the Strood Union the Christmas fare for 1914 was limited to 6oz beef or mutton, with parsnips and potatoes, 1lb of plum pudding, 1 pint of beer or mineral water, 1oz of tobacco for men and 1/2oz of snuff for women. The need for beer to be offered was questioned as it was not offered at other times of the year (Chatham, Rochester & Gillingham Observer, 14 Nov 1914). The inmates got their beer in 1914.

In 1915 the Christmas plum pudding was reduced from 1lb to 3/4 lbs ; in 1916 it was proposed to replace the Christmas beer allowance with the “far more exhilarating” coffee – the motion was not accepted (Chatham, Rochester & Gillingham Observer,28 Oct. & 4 Nov. 1916).

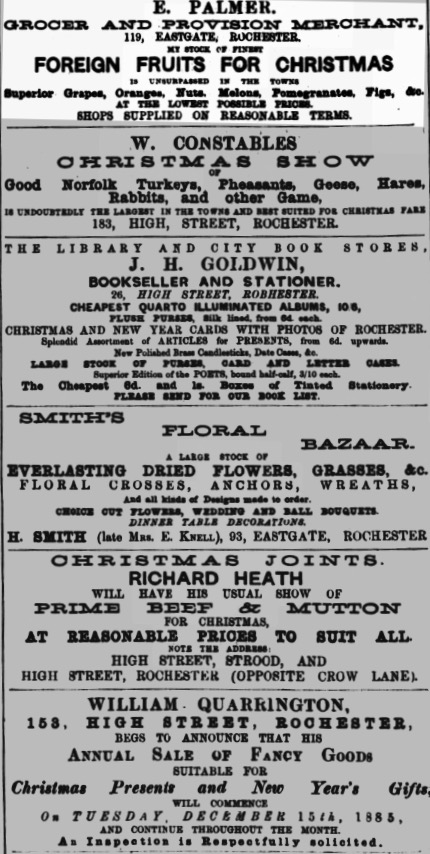

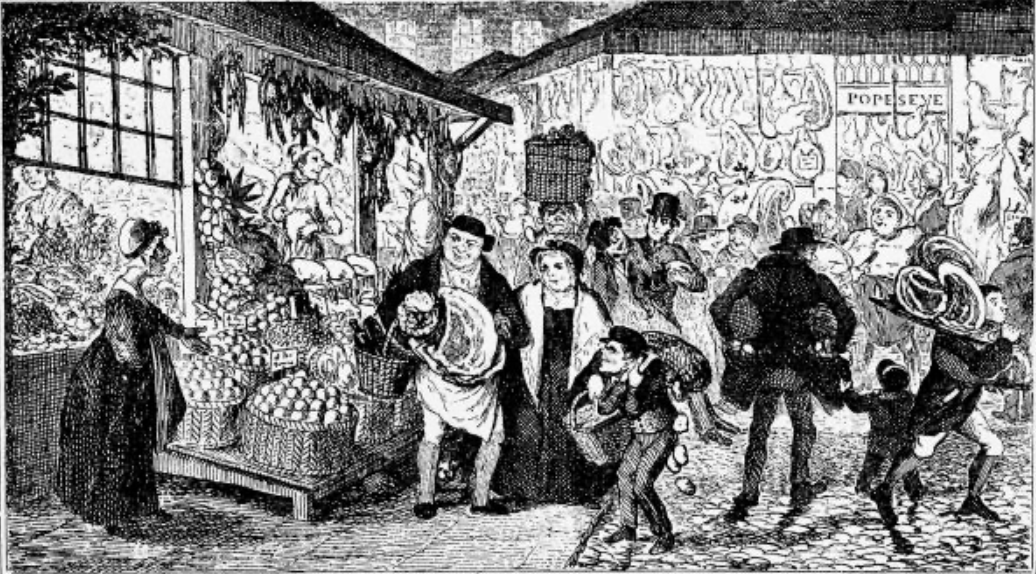

Christmas Shopping

As today shopkeepers went to some length to create festive displays as Christmas sales were good for their business. During the 19th century competition between traders along Rochester High Street would have been intense as there was often a choice of butchers, poulterers, grocers and bakers etc. They all, therefore, went all out to display their most choice items in their windows. Based on news reports one could perhaps assume that the inhabitants of Rochester and Chatham participated in ‘extreme window-shopping’ as they went around the city enjoying the efforts that the competing traders had made to out-via each other.

As today shopkeepers went to some length to create festive displays as Christmas sales were good for their business. During the 19th century competition between traders along Rochester High Street would have been intense as there was often a choice of butchers, poulterers, grocers and bakers etc. They all, therefore, went all out to display their most choice items in their windows. Based on news reports one could perhaps assume that the inhabitants of Rochester and Chatham participated in ‘extreme window-shopping’ as they went around the city enjoying the efforts that the competing traders had made to out-via each other.

In 1846 it was noted that the shop of the butcher Benjamin Bassett of Eastgate had put on a spectacular display that nightly attracted the attention of the admirers of fine meat. He was though not without competition. Mr Balcomb of St Nicholas had killed two prize oxen, and two prize winning sheep that had only been fed on grass (West Kent Guardian, 26 Dec. 1846).

Perhaps today Christmas is more about toys and the giving of gifts – as well as food. In the past it seems the prime focus was on food – perhaps supplemented with a small luxury gift. But by early the early 20th century shops in Rochester were advertising “yuletide gifts for the fair sex” and “toys that children will cherish” (Chatham, Rochester & Gillingham Observer, 5 Dec. 1914).

Christmas Eve Shopping

Shopping Could be Dangerous!

Although the shops remained open late into the evening shopping was not easy after dark. In 1863 representation was made for increased street lighting in Rochester between October and February. The council however decided that as it had spent so much on the installation of hydrants it could not afford more street lighting.

Two women could have had their Christmas of 1901 spoilt following being blown from their feet whilst passing the Guildhall in Rochester High Street. The cause was that electric cables that had been laid in the same chamber as a gas pipe, caused a spark that ignited escaped gas (Henley Advertiser, 14 Dec. 1901).

During the Great War

Shopping in the evening during WW1 was made even more difficult as black-out regulations removed what lighting was available and shopkeepers could be prosecuted if they allowed light from their store to illuminate the street. It therefore encouraged traders to persuade people – largely women – to shop during the day.

Tallyman Club

To encourage trade and to perhaps help household spread the cost of Christmas and other essential items, Featherstone’s, along Chatham Intra, promoted their ‘tallyman club’ in 1914/15. Notices were placed in newspapers explaining the scheme, and offering assurances that participation in the scheme was not “degrading”. A meeting was held in the Fountain Head public house to explain it. Membership of the scheme enabled members to make a payment of a certain sum per week – “in the same way as you pay the rent”. This payment then enabled the member to secure clothing and other necessities to the value of several pounds at any time when they were needed. Featherstones’ offered the assurance that it would happily refund money if the ordered goods are were not as expected (e.g. Chatham, Rochester & Gillingham Observer, 9 & 16 Jan. 1915).

During the Second World War – Shop to Defy Hitler

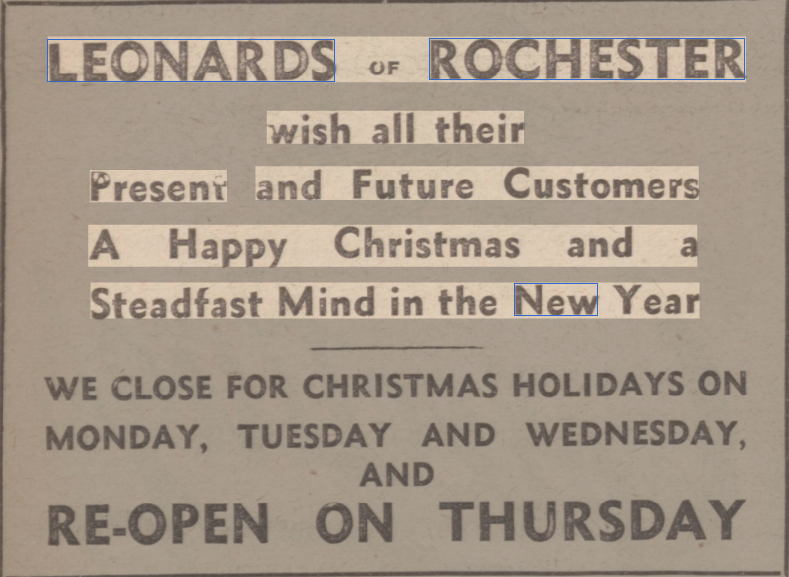

Advertisements placed by the traders acknowledged the impact of the war and tried to use it to encourage shopping as a means to defy Hitler. Leonards of Rochester wished their customers “A Happy Christmas and a Steadfast Mind in the New Year”. Leonards also closed for three days for the Christmas holiday. The Value Villa located near the Majestic Cinema, Rochester, encouraged people to “Forget Hitler” and to think about purchasing furniture at pre-war prices (Chatham News, 22 Dec. 1939).

Advertisements placed by the traders acknowledged the impact of the war and tried to use it to encourage shopping as a means to defy Hitler. Leonards of Rochester wished their customers “A Happy Christmas and a Steadfast Mind in the New Year”. Leonards also closed for three days for the Christmas holiday. The Value Villa located near the Majestic Cinema, Rochester, encouraged people to “Forget Hitler” and to think about purchasing furniture at pre-war prices (Chatham News, 22 Dec. 1939).

Workers at Christmas

Today we take it for granted that non-essential workers will have a holiday over Christmas and many services will be run by a skeleton staff until the new year. This was not always the case.

Shop Workers

The hours of shop workers during the 19th century were long and paid holidays were rare. It was not until 1886 that the working week of a shop assistant was limited by law to 74 hours. It wasn’t until 1938 that legislation was passed giving certain workers the right to a paid holiday.

By 1843 when Dickens wrote of Scrooge in his Christmas Carol, some employers were giving days off over the Christmas holiday. Whether it was paid or not is a moot point. In 1842 nearly all the shops in Rochester, Chatham and Strood closed for Boxing Day (West Kent Guardian, 31 Dec. 1842) – but could that have been because Christmas Day that year was a Sunday as it wasn’t until the 1871 a law was passed making Boxing Day a Bank Holiday.

Dockyard Workers

In 1860 the workers employed in Chatham Dockyard were ordered by the Admiralty to take extra holiday over Christmas. This though was not so much of a gift as the workers were required to make up the time after Christmas by working extended days – 6am to 8pm (South Eastern Gazette, 25 Dec.1860 – note paper published on Christmas Day). In 1863 the dockyard workers were required to put in extra time before Christmas in order to have an extra day off (Maidstone Journal, 8 Dec. 1863).

Postal Workers

One has to take their hat off to the postal workers during WW1 and WW2 – who were mainly women – who ensured the massive increase in the amount of Christmas post got through on time. In 1914 it was reported that all post had been delivered by 11am on Christmas Day (Chatham, Rochester & Gillingham Observer, 2 Jan. 1915).

During WW2 there were Christmas Day deliveries. To cope with the large increase in post added to by the many children who had been evacuated from Medway, the Corn Exchange at Rochester was taken over as the ‘sorting office’ for Rochester and Chatham.

Railway Workers

For Christmas 1869 the staff at Chatham railway station were praised for the use of very simple materials to tastily decorate the station with “evergreens, devices and festoons of coloured paper”. Strood station though was said to have been devoid of any signs of Christmas but the porters had artistically decorated their room in which they no doubt enjoyed the wine and spirits given to them by the station master (Chatham News, 1 Jan. 1870).

The Military

The military also made their contribution to creating and entering into the festive spirt across the towns. There were parades to church on Christmas morning before the men returned to their highly and tastily decorated barracks and rooms. The commanding officers of the various corps “subscribed liberally” towards providing entertainment for their men. It was also reported that in 1869 that all the men were given a small sum of money from the profits of their canteen (Chatham News, 1 Jan. 1870). The tone of the news report suggests this could have been a new use for the profits.

Church Services

Clearly there is nothing notable about churches holding services over Christmas – that is until war was declared in 1914. By Christmas 1914 the Medway Towns were packed with soldiers heading for the Front and civilian workers. The incomers would have mainly been young men and many away from home for the first time. It would have also been clear to the young men that many did return from the Front and those who did were badly injured. In these circumstances it’s not surprising that the churches around Medway were packed at Christmas.

In 1915 the Cathedral at Rochester held seven services on Christmas Day. To cope with the numbers wanting to take Communion it was administered in the Nave for the first time since the Reformation in the 1540s (Chatham Rochester & Gillingham Observer, 1 Jan. 1916).

Christmas 1918 was one of extreme emotions. Hostilities were over. Those who had lost loved ones to the war or to what we know today as Spanish Flu, would not have shared the joy of those, who without loss, who would have wanted to make it a Christmas like no other.

On Christmas Day 1918 the Cathedral bells started a joyous peal at 6:15am and continued to the start of the service at 7am; services though at the Cathedral were not well attended (Chatham, Rochester & Gillingham News, 28 December 1918).

Entertainment

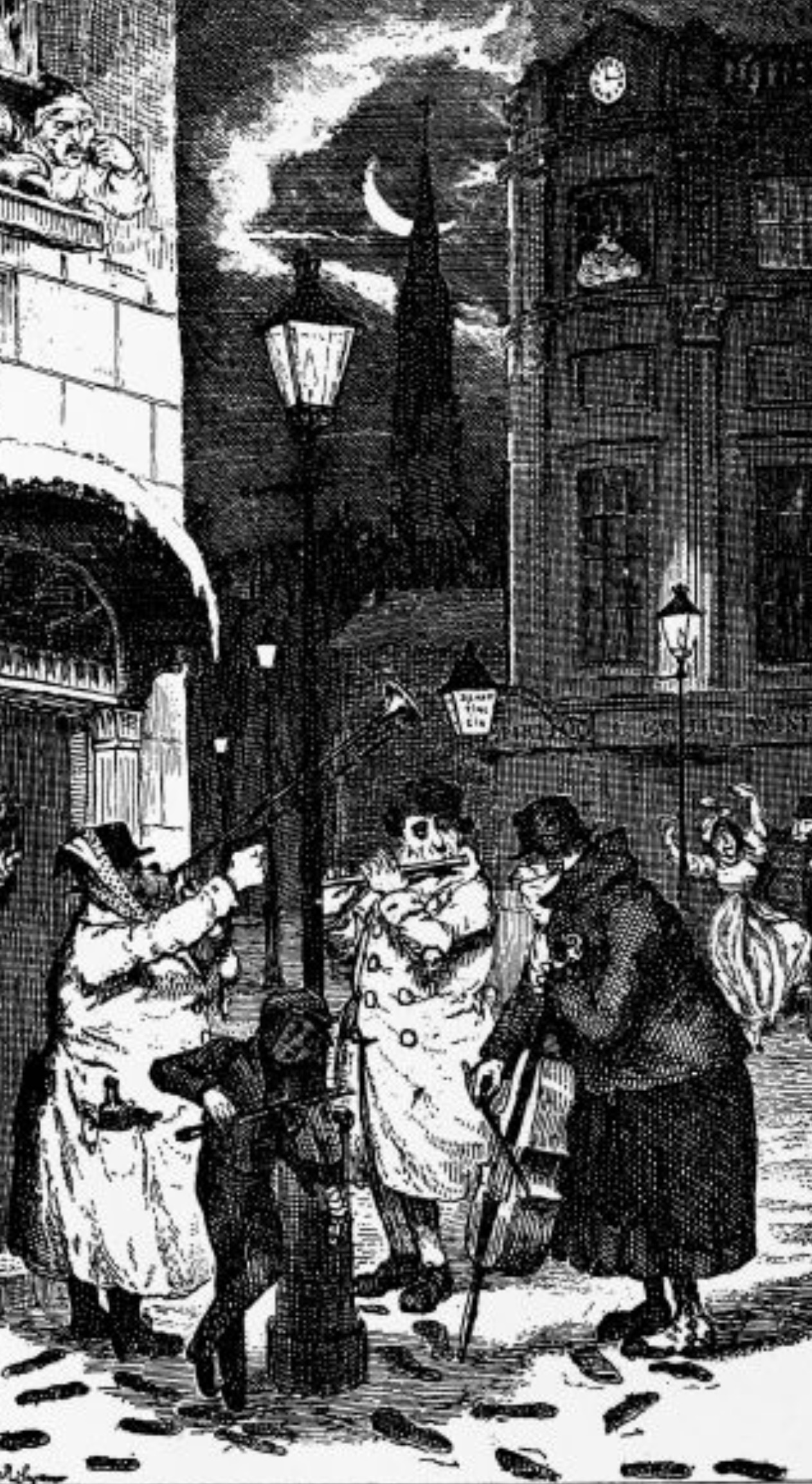

Street Entertainment

From medieval times to 1835 the councils of major towns and cities employed street musicians known as Waites/Waits or the Mayors Minstrels; they were salaried, provided with a uniform and a silver chain of office. With the reorganisation of local government in 1835 (Municipal Corporations Act) the Waites were disbanded. In Rochester the civic musicians were quickly replaced by William McGeorge a local musician who set up a group known as ‘The Christmas Waits’. The group played music on the streets of Rochester over the Christmas to raise money.

William McGeorge was acquainted with Charles Dickens. It may therefore have been a homage to him that Dickens in his Seven Poor Travellers makes reference to leaving the traveller’s house on Christmas Day in search of the street musicians…..

“As I passed along the High Street, I heard the Waits at a distance, and struck off to find them. They were playing near one of the old gates of the City, at the corner of a wonderfully quaint row of red-brick tenements, which the clarionet obligingly informed me were inhabited by the Minor-Canons.”

Reports of the death of William McGeorge in 1928. stated that he had run the Rochester Christmas Waits for 65 years (Hampshire Telegraph, 4 May 1928). An advert placed by Tunbridge Wells Gas Company promoting the use of gas for cooking, seems to suggest that the Waits may not have always been very ‘musical’. The Company claimed the housewives not only had to endure Waits on the street they had to endure a Wait at home whilst the oven reached temperature – unless they used gas (The Courier, 22 Dec.1933).

The Panto-Season – no glimpse of the past could not include Pantomime – even though they are not in the past!

As is the case today a good pantomime season was critical to the overall finances of the theatre. In 1863 the manager of the Theatre Royal/Lyceum at Rochester stated that Rochester was the place for short theatrical campaigns (Chatham News, 19 Dec. 1863). The Theatre Royal, also know for a period as the ‘The Lyceum’ seems to have always had trouble making money. It lacked a significant patron or sponsor so its income was entirely dependent on attendances and repeat attendances. This would have driven having more short-run shows, or running shows concurrently.

As today the Christmas / Panto Season was critical to the survival of Rochester’s theatre. We would recognise some of the pantomimes that were put on but some seem to have rather niche and unlikely to be put on again, or be acceptable – such as ‘Blue Beard’ who was a serial wife killer.

1844: The pantomime(s) were announced to be “The Fairy of Silver Lake” and “The Harlequinade” (West Kent Guardian, 13 April 1844). (Pantomimes were originally called Harlequinades. The show would start as a serious play. Part way through a mischievous harlequin would appear on stage and disrupt the show. Specially constructed scenery would then collapse as he hit it. Stage hands (actors) would appear and the show would turn into a farce.)

1855: On the evening of Boxing Day the Theatre Royal was packed to overflowing by people determined to be amused with everything and everybody in the pantomime Harlequinade (Maidstone Journal, 2 Jan. 1855).

1860: The pantomime which was to open on Christmas Eve was “Guy Faux” – that was to include the character of Columbine from Harlequinade (Bell’s Weekly Messenger, 29 Dec. 1860). In 1835 there was a pantomime tilted “Harlequin and Guy Fawkes” put on at the Covent Garden Theatre.

1869: A number of Christmas amusement were put on at Rochester Theatre over the Christmas period. These include the Harlequinade and every night the evening concluded with the “grand Christmas Pantomime of “Aladdin or the Wonderful Lamp” (Chatham News, 8 January 1870). On 8 January a free show was put on for the children of the Medway Union (Chatham News,15 Jan. 1870).

1870: The Christmas programme put on at the Royal Lyceum, Rochester, was a mixture of a tragedy – George Barnwell (otherwise known as The London Merchant or, The History of George Barnwell), a new original pantomime “Undine, the Watch on Rhine, or Harlequin The Gnome King and Britannica, The Sweet Spirit of the Water”, and 1792 – the tale of the French Revolution with a renditioning of La Marseillaise in the second act (Chatham News, 3 Dec. 1870).

1880/81: The grand comic pantomime – Gulliver’s Travels played to a packed Theatre Royal at Rochester, nightly for six weeks. It was described as “the most gorgeous and elaborate production ever seen upon a Rochester stage”. As well as giving ticket prices (2s for a reserved seat and 6d in the balcony) patrons were advised that the theatre would be “Comfortably Warm” (Gravesend Reporter, 12 Feb. 1881).

1882: The owner of the Theatre Royal at Rochester claimed that the season’s production of – Blue Beard – was the theatre’s most successful pantomime (The Era, 27 Jan. 1883). (This seems to have been the panto of the year as it was put on in theatres across the country.)

Another major venue for theatre and pantomimes arrived in Medway in 1912 – the Empire Theatre at Chatham. (It was on the site near to what was / is Anchorage House).

1918: The officers and men of the Royal Naval Barrack at Chatham put on a matinee performance of “Mother Goose or Lay an Egg” at the Empire Theatre, to raise money for local war charities. All the parts were played by men (The Sketch, 8 January 1919).

The theatre was converted which enabled the putting on of ice shows.

1954: “The scintillating xmas pantomime Cinderella on Ice” was presented at the Empire Chatham – “a real pantomime, with full dialogue, lovely music and presented on real ice” (Kent & Sussex Courier, 3 Dec. 1954). The theatre was closed for one week before curtain-up to enable the ‘stage’ to be set (Kent & Sussex Courier, 10 Dec. 1954).

January 1958: Sleeping Beauty on Ice. Claimed to be the the theatre’s greatest entrainment of the season and being too good to miss (East Kent Gazette, 10 Jan. 1958).

Pantomimes are still a Christmas staple – but there are many still around today who can better tells of the later Christmas shows.

In Conclusion

It is clear that there was never a romanticised, sentimental, perfect Christmas. There were and always be, those who are more fortunate than others. But fortunately despite many adversities we continue to strive to ensure Dickens’s “Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come” remains within the covers of his book.

Sources cited in text.

Pen drawings from The Book of Christmas, Thomas K Hervey, 1852.

Geoff Ettridge aka Geoff Rambler – 21 December 2021