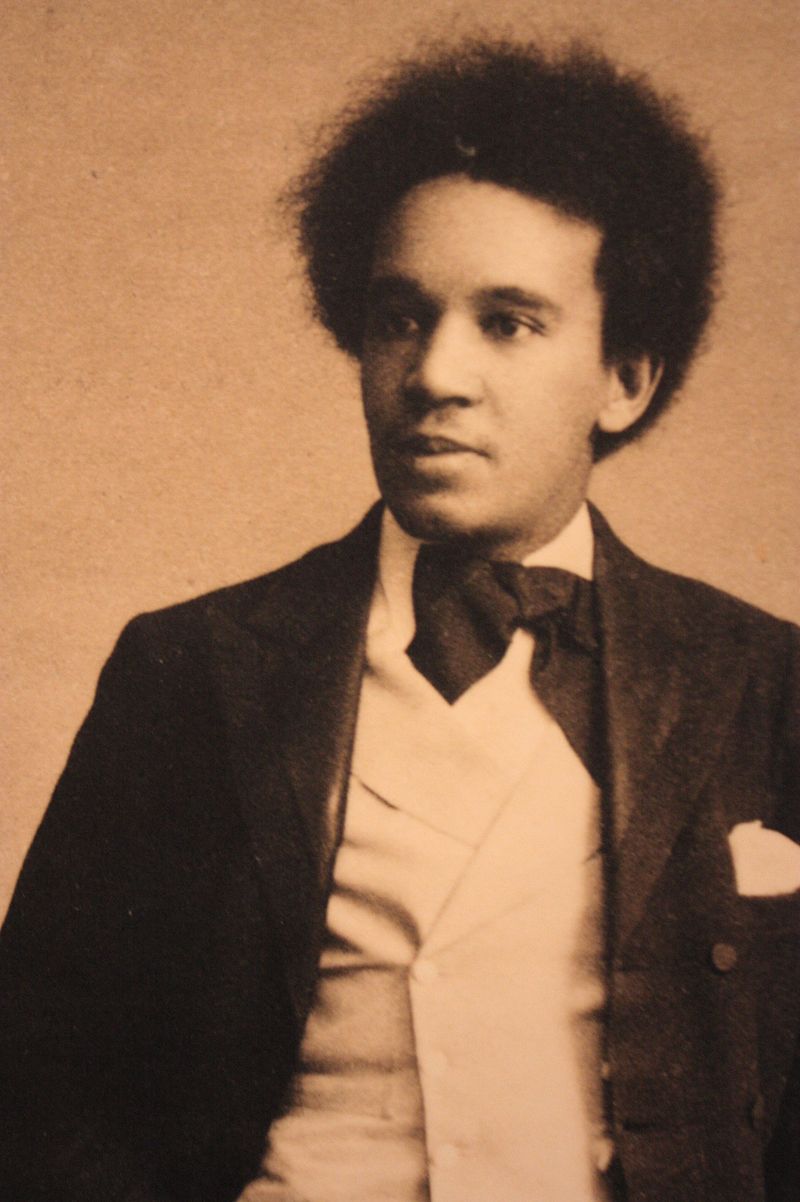

On 14 June 2022 the BBC visited Rochester to record material for an episode of Celebrity Antiques Road Trip. Along with Philip Serrell, Eric Monkman (of University Challenge fame) BBC came to the cathedral to record Rochester Choral Society singing a piece from Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s ‘Hiawatha’ – a piece that he had conducted the Rochester Choral Society singing about 60 year previous. The image below was taken around 1893 and probably more accurately shows the Coleridge-Taylor who would thave been familiar to the members of the choral society he conducted .

What was notable was that Coleridge-Taylor, an eminent musician in the early twentieth century, agreed to take rehearsals of the amateur Rochester Choral Society and to conduct its performances. What was not of significance at the time, but is more so today, was his racial and cultural background.

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was one of the most innovative composers and conductors of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Had he not died so young he could well have been up amongst the Elgars of the world; yet for six or seven years between 1900 and 1907, he was the conductor and choral coach for the Rochester Choral Society. Certainly by all accounts the Rochester Choral Society was good, but the fact that such a promising young musician would coach an amateur group probably says more about how little money a musican, back then, made from their compositions, and therfore needed alternative sources of income.

The story of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor is intriguing and, today, disturbing in a racist sense. His mother was a white English woman and his father, a doctor who trained at Kings College London, was from Sierra Leone. Although today Coleridge-Taylor’s background would probably be regarded as worthy of note, reports at the time of his life focused on his musical talents and made little mention of his cultural heritage other than in a positive way in terms of the influence that music from Africa may have had on his compositions.

Despite being regarded as an outstanding musician of his time, little is known of Coleridge-Taylor today, even in the Medway Towns where for over six years he made a highly valued contribution to music-making in Rochester. His music is seldom played and has only been performed by the Rochester Choral Society three times since his association with the society ended in 1906/07. His ‘disappearance’ has left us wondering whether it was the man and not his music that fell out of favour, as racism became more pervasive in postwar Britain.

‘Hiawatha’ was last performed at Rochester in 1965. Our Membership Secretary, Rosemary Clements, recalls that a woman walked out of the cathedral in disgust because she felt the work was not suitable to be performed there.

As it is nearly 60 years since a work by Coleridge-Taylor was performed in Rochester, I would like to re-present him and to encourage performances of his music. This is not just in recognition of his past connection with music making in the Medway Towns, or because it is time to recognise the contribution that people from minority communities have made to shaping our culture, but because his music – to my ear at least – is well worth hearing.

Brief Biographical Background

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was British-Sierra Leonean composer and conductor. He was born in London and brought up by his single mother Alice Hare Martin living in her father’s household. It would appear that his father, Dr Daniel Peter Hughes Taylor, having been unable to establish a medical practice in Britain, returned to Africa not knowing that Alice was pregnant. Alice’s family was well-to-do and clearly familiar with the arts in that she named her son after the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who shared the name ‘Taylor’ with Samuel’s father.

By all accounts the family where socially well connected. Before the Great War/WW1 social class was the great determinant and Samuel’s race may well have been of little consequence.

Reports of the young Samuel suggests he was a child prodigy when he came to music – showing an early talent for playing the violin and gave a concert at the age of eight. In his obituary it was recorded that someone who had known Samuel as a child described him as a “boy so beautiful in mind that he can produce nothing but beautiful music” (Norwood News, 7 Sept. 1912). (Samuel’s gentle and encouraging personality was something that many noted and endured throughout his life.)

Samuel was taught the violin by his grandfather Benjamin Holman who was listed in the 1861 census for London as being a professor of music.

Samuel’s prospects as a musician were enhanced when his abilities were recognised by Col Herbert A Walters, the choirmaster of a Presbyterian church, and who later sponsored him at the age of 15 to the Royal College of Music (Sept 1890).

Samuel first studied the violin but his composition skills were soon recognised with him winning a scholarship to study composition in 1893. Music critics of the time noted that Samuel had his own distinct style that neither reflected the style of his teachers nor other composers (Croydon Guardian and Surrey County Gazette, 7 Sept, 1912).

Samuel Coleridge-Taylorleft college in 1897 and in 1892, aged 22, composed the cantata ‘Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast’ that made his reputation. This work set to music Longfellow’s poem ‘Hiawatha’. The finished work became a trilogy. The first part ‘Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast’, then ‘The Death of Minnuchaha’, and finally ‘Hiawatha’s Departure’. The composition as a whole was performed for the first time at the Royal Albert Hall on 22 March 1900. At the time of his death Taylor was writing ‘Hiawatha’ as a ballet.

Although Taylor appears never to have met his father or indeed travelled to Africa, it is worthy to note that there was a strong African influence in his work. Perhaps this came as a consequence of his mother ensuring that he was brought up aware of his cultural heritage; it’s also worthy of note that Taylorl’sfuneral was attended by a large group of people from West Africa. They brought with them a wreath in the shape of Africa with a red patch to mark Sierra Leone. The wreath carried two inscriptions – one ‘From your African brothers’ and the other ‘From the sons and daughters of West Africa resident in London’.

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor comes to Rochester

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor commenced his association with the Rochester Choral Society shortly after graduating in 1897, and before his reputation had fully come to the public’s attention with the performance of his complete work of ‘Hiawatha’ at the Royal Albert Hall.

At a time when composers did not receive royalties for their printed scores, their musical income came from teaching, conducting – particularly their own works – or adjudicating at choral contests. Taylor was much in demand as an adjudicator because of his kind personality. Is it perhaps that this is how he came to the attention of the Rochester Choral Society? The request by the society for him to take up a position with them could have been an attractive proposition for Taylor as the train journey to Rochester from Croydon would not have been difficult.

Rochester Choral Society

It would not just have been convenience that persuaded Taylor to accept the appointment as conductor and chorus trainer with the Society as that could have implications for his reputation. The risk of association with the Rochester Choral Society, though, was low as the society was held in high regard as, in the late 19th century, it attracted some of the foremost artists of their day, including Miss Clara Butt (A History of Rochester Choral Society 1873-1973 p 31).

At a committee meeting of the society in 1899 it was decided to perform two pieces by up-and-coming composers – ‘King Olaf’’ by Elgar, and Taylor’s ‘Hiawatha’ – the latter being performed in 1899. (The performance was probably of the first part of the trilogy as the full work was not performed until 1900.)

The society’s annual report for 1901/02 recorded: “When two years ago Mr Coleridge-Taylor came to conduct his ‘Hiawatha’ his ability as a conductor and chorus trainer was so manifest that the performing members of the society spontaneously offered double the amount of their fee in order to contribute their share of the cost of retaining the services of so eminent a musician”.

It was recorded that the advantage of this appointment to the “whole society was obvious, and its reputation in the musical world is more than maintained”.

And so it was that Coleridge-Taylor was appointed as conductor and ‘choirmaster’ – a position he held with the Rochester Choral Society for seven years. During his association he encouraged experimentation with opera and seems to have conducted a performance of his ‘Hiawatha’ twice. His last concert with the society was Dvorak’s ‘The Spectre’s Bride’ and was probably performed in Spring 1906.

How the society’s association with Taylorended is unrecorded but Vera Black, in her history of the society, speculated this might have been due to the society’s deteriorating financial position.

Impact on the wider music scene of Rochester?

It is hard not to imagine that Coleridge-Taylor, through a combination of his skill, personality and seven years association with Rochester Choral Society, did not inspire musicians in the area. One such musician may well have been Miss Goldie Bakerof whom it is reported that he had said had “.. immense tone for so young a violinist and there is a feeling of sound musicianship and thorough understanding in her playing which is very rare and very delightful” (e.g Gravesend & Northfleet Standard, 8 Aug. 1913).

The first reference I’ve discovered to Miss Goldie Bakerwas when she played solo pieces, aged 15, at the Assembly Room, Bath. Here she performed Mendelssohn’s violin Concerto, so well that the audience demanded an encore (Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 21 Jan. 1904). Later that year she was awarded the Kent Scholarship to study the violin tenable for three years at £100 per year at the Royal College of Music (Globe, 28 Mar. 1904). A year later she appears to have received the status of an Exhibitor at the Royal College of Music, (East Kent Gazette, 15 July 1905).

By 1910 Miss Baker, then aged about 21, was a prominent performer and had established herself as a music and singing teacher working from her home at 38 Frindsbury Hill, Rochester, and 10 The Broadway, Sheerness, (Sheerness Times Guardian, 3 September 1910).

Miss Goldie Baker continued to perform at concerts and fundraising events and music clubs into the 1950’s. She often performed as the violinist or cellist in a trio with her sister, May Baker, and Miss L Homewood. In 1950 she participated in a programme performed at All Saints Church, Frindsbury, that included Vera Black singing soprano (Chatham, Rochester and Gillingham News, 2 May 1950).

Twenty-four Negro Melodies – an indirect connection.

Around 1902 Coleridge-Taylor composed ’24 Negro melodies’ based on African fold songs. One piece was a Yoruba folk song, Oloba Yale mi, recommended by Victoria Davis – it can be found on Spotify. Victoria was the daughter of Sarah Bonetta Forbes a black princess who as a child landed at Chatham from a ship the British had sent to disrupt the slave trade, and who spent a large part of her adolesence in the care of Rev & Mrs Schön in Canterbury Street, Gillingham, Kent.

Obituary

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor died, aged 37, after a short illness on 1 September 1912. Many people sent tributes including one from Rochester Choral Society:

“Since 1901 he (SCT) has often visited us, and helped to make our concerts the more enjoyable, that we feel we have lost a friend who had the power to fire the imagination and poetry that is in all of us, and to enable us to share some of the tremendous vigour and musical imagination that was his. When, in 1897, he came before the public with impetuous eagerness, a very young man, full of abounding musical energy and originality, we hoped that circumstances would be kind to him, and that he would receive from the public to whom he gave so much pleasure …”

The tribute from Rochester acknowledged that Taylor would earn little from his music scores, no matter how popular his music may be (Norwood News, 7 Sept. 1912).

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was survived by his wife and two children – a son, Hiawatha Bryon, born 1901, and a daughter, Gwendoline, born in 1903. Both went on to follow musical careers and were identified as black musicians.

Geoff Ettridge aka Geoff Rambler

075 2516 1766

http://www.geofframbler.blog

www.facebook.com/geofframbler

Sources:

Contemporaneous news papers.

History of Rochester Choral Society 1873 – 1973. Vera L Black.

Black Mahler – The Samuel Coleridge-Taylor Story. Charles Elford. 2008. (Treat with care – facts from SCT’s life have been merged into a novel.)

I am also grateful to Rosemary Clements for searching out information concerning the Choral Society’s performance of ‘Hiawatha’. It was performed in 1900, 1901, 1905, 1921, 1962 and 1965.

Comments are closed.