Apart from the outside, the most impactful part of Eastgate House is the three ornate plaster ceilings. There is one on the first floor and two on the second floor. These ceilings are part of the first phase of the construction of Eastgate House at Rochester, Kent.

Eastgate House was built for Peter Buck towards the end of the Tudor period (1485-1603). Tudor art and architecture was loaded with iconology and symbolism – real and mythological. There were heraldic devices confirming social status, and roses provided a nod of respect to the Tudor monarchy. Many other forms were drawn from the natural world. All the different forms would have had some symbolic significance. Perhaps no different to the way emojis are used today – they convey information and emotions.

This blog looks at the design of these ceilings to see if they could reveal something of Peter Buck, his family and the times in which they lived. The following are suppositions but have shaped by significant historical events, iconology/mythology, and the family’s biography. However, without talking to the artist it is difficult to discover the meaning that they put into their work. The conclusions I’ve drawn are therefore inevitably speculative.

You are invited to reach your own.

__________________________________________________

Work on Eastgate House began in 1590/91, and it’s likely that the ceilings were constructed before 1603. The design of the first-floor ceiling celebrates Peter Buck’s civic status. Central to the room is what is referred to as an ‘Achievement’. This is made up of the holders awards. In this case it contains the Buck family’s coat of arms and the family’s crest.

This ‘Achievement’ does not include what are referred to as ‘Supporters’. These are usually creatures placed on either side of the coat of arms of persons who have been knighted. Samuel Pepys records that this honour was bestowed on Peter Buck by James I in 1603. If Buck had received this honour during the time the ceilings were being crafted, it would have undoubtedly been incorporated into the design.

Why incur the cost of installing ornate plaster ceilings?

The Elizabethan period saw the rise of the gentry — people whose status was not inherited but earned. Rochester was well placed for people to make their wealth. Rochester was about 6 hours travelling from London. Much trade also came through the area. This was enabled by the bridge, the civilian dockyard at Rochester and an expanding naval dockyard at Chatham.

The aspirations of those with increasing wealth is evident in Rochester. There are number of ‘statement properties’ in the area that were constructed during the Tudor period. The owners of these properties appear to have come from families that had earned their wealth.

- Abdication House (now gone but was ‘sufficient’ to accommodate James ll before his abdication). It, along with the Great Hermitage at Higham, belonged to Richard Head. He was the son of a yeoman who made two good marriages. The dowry of this first wife included a fleet of merchant ships. The dowry of his second wife included a considerable portfolio of Rochester properties.

- Eastgate House – built by Peter Buck – a senior ‘civil servant’ from Chatham Dockyard. His wealth is unknown but he had two marriages – both of which would have been accompanied by dowries.

- Restoration House – built by Henry Clerke and his son Francis – both wealthy lawyers.

- Satis House – acquired by Richard Watts – victualer to the navy at a time it was expanding at Chatham. Through his Will he was the founder of the Richard Watts Charity.

Properties become a Statement of Wealth and Status

It would seem quite probable that the aspirational “middling people” (nouveau riche) would have to styled themselves on the aristocracy. Just as today, people who have recently acquired wealth have a tendency to become showy. This could have been particularly the case during the Tudor period.

It started with the collapse of serfdom in the 14th century following a major outbreak of the plague. Many of the non-landed class began to establish themselves as merchants, craftsmen, and professionals. As a show of their growing wealth they began to wear clothes and jewelry previously worn by the nobility. Eventually laws were passed to stop artisans from wearing particular cloths and colours. As the wealth of the mercantile classes grew they wanted properties that matched the style of those of the aristocracy.

The installation of ornate ceilings could have been one such way of demonstrating wealth.

The Ornate Ceilings of Eastgate House

Only three rooms in Eastgate House are ornate. All are in the first phase of construction and are on the first and second floor. The ground floor ceiling is plain. It’s perhaps also worth noting that ornate ceilings were not installed in subsequent phases of construction. Perhaps the need to be showy diminished as Peter Buck’s position in Rochester became established? Some sources suggest he became the mayor of the City of Rochester. He is though not included in the list of mayors, produced by the Guildhall Museum at Rochester. Samuel Pepys states that Buck was was knighted in 1603 by James ll, and the accounts of the Richard Watts Charity identifies him as being its ‘Provider’ 1608 / 09.

The cost of commissioning bespoke ceilings would have been significant. It’s therefore likely that Peter Buck would have provided a design-brief for the artisans responsible for the work.

What that brief was is lost in the mists of time— if indeed it was ever written down. The following is therefore based on suppositions. These suppositions have roots in historical context, iconology/mythology, and family biography. They also consider the intentions that may have been behind the commissioning of the ceilings. Then there is how the artist interprets the brief they’ve received.

You may form your own opinions— but ‘look beyond looking’ at the ceilings and ‘see what you can see’.

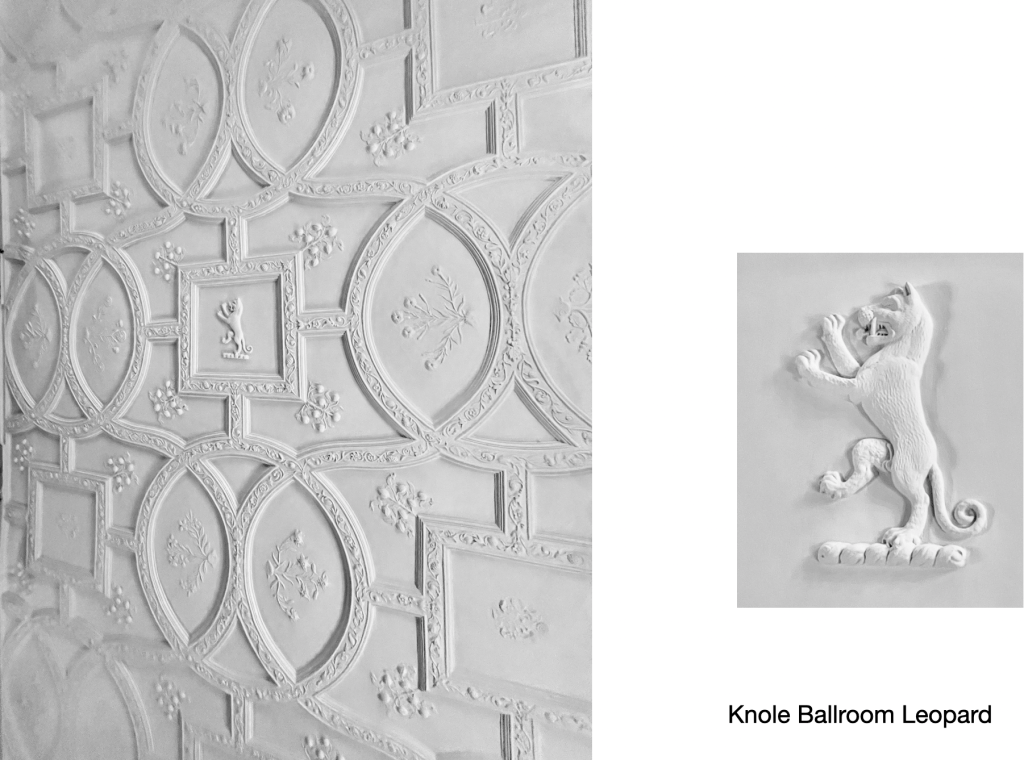

Eastgate House may appear grand alongside other dwellings at Rochester. However, it is a ‘poor relative’ in comparison with the aristocratic homes such as Knole Palace. The design of the ceilings at Eastgate House lacks fineness in design and crafting. This is especially seen when comparing them with those of Knole Palace. By comparison the Eastgate ceilings seem somewhat over-the-top? Lacking class and finesse? (There are some ceilings in Cobham Hall that are masquerading as Tudor / Jacobean. The ceiling of the room named the Elizabethan Room was created around 1817 by George Repton.)

Hierarchy of Space and Access

Eastgate House has three stories – not including the cellar. Each I would suggest becoming more private. This arrangement is evident in Royal Palaces. The most important people having access deeper into the palace and eventually the monarch’s bedchamber.

The curators at Eastgate House have designated the ground floor Peter Buck’s Study. This seems improbable. In Tudor houses the ground floor was where servants worked. It was where food was stored and prepared. In a time before refrigeration, there could be almost daily deliveries. Office-type transactions might have occurred on the ground floor. However, I suspect that Peter Buck conducted his important business and meetings, in the room on the first floor. I’ve have titled that room the Heraldic Room. The rooms on the second floor would then have been the family’s private and personal space.

The Heraldic Room – Room 1 on the First Floor

At Eastgate House, this room has been designated as being the Family Room. I would suggest that this room was probably Peter Buck’s study. The designs in the ceiling of this room would have left visitors in no doubt of Peter Buck’s ‘credentials’.

Of the three rooms with ornate plaster ceilings the ceiling of this room is the finest. It appears to have been made by a craftsman. By comparison the ceilings of the other two rooms appear amateurish.

The geometric strap work that was popular in Elizabethan interiors and floral features have been executed with great care and skill. The strap work would have been created over a framework crafted by a carpenter. The consistency between similar floral features and the bosses points to them have being made with a mould. The mould would also have been made by a carpenter. It was not unusual for carpenter and plasterer to work as a team.

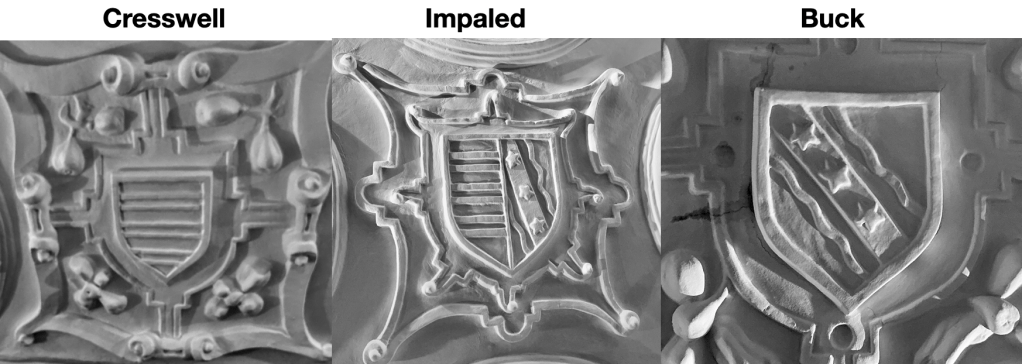

The principle features in the ceiling of this room are the heraldic honours associated with the Buck family. It includes the coats of arms for Peter Buck and the family’s crest. The bottom right image of the array below, is known as an ‘impalement’. This ensures the status of descendants from subsequent marriages are recognised. This room does not include the coat of arms of his wife’s family, the Creswells. The design of this ceiling is very much about Peter Buck and his male descendants by his second wife, Mary Creswell.

The heraldic images today are no longer coloured. It possible that the early ceiling could have been painted as this was fashionable towards the end of the 16th century.

For more about the heraldry of the Bucks and Creswells visit – Heraldic Devices at Eastgate House, Rochester, Kent.

The message in the design of the ceiling in this room is both subliminal and explicit. It conveys wealth, pride in achievement, and an almost ‘in your face’ statement of importance. This was unnecessary for the aristocracy where their status was well appreciated at the time.

The ceiling of the ballroom at Knole Palace includes leopards. These were adopted as ‘supporters’ of the family coat of arms by the Sackvilles in the 16th century.

The following images are from two of the decorated ceilings at Knole Palace – the Reynolds Room and the Ballroom. They were probably created between 1604 and 1607.

The ceilings in the Reynolds Room (above) and the Ballroom (below) are designed with delicate decorative details. The strap work is more decorative than that in Peter Buck’s study. The consistency in the quality suggests extensive use of moulds. Many leopards are included in the design of the ceilings at Knole. They all look very similar and lacking in detailing. (The creatures included in the designs of the second ceilings at Eastgate House – described below – show considerable ‘individuality’. Could this be because they were all individually handcrafted and not replicated in a mould?)

The Sackvilles can rightly be regarded as ‘old money’. Their status within their network would have been well established and known. The Bucks were ‘new money’— with no known aristocratic roots. Their place in society would therefore not have been established or widely known. This could explain the prominent display of the Bucks’ achievements, emphasising status and impressing (or socially intimidating) visitors. This room is not about celebrating family. This room is about the Bucks and their status.

Moving up to the second floor of Eastgate House

This floor would have been the personal space of the family. A place to have fun and celebrate family life and individual achievement’s — not so different from today? The designs in the ceilings of the two rooms are not as impressive as those in Peter Buck’s study. They also compare poorly with those in Knole Palace. This is perhaps not unexpected. The Jacobean ceilings in Knole Palace were created by the Royal Plasterer – Richard Dungan.

The Marine Room – Room 1 on the second floor

This room is designated as the ‘Memory Room’ by the curators of Eastgate House. However look closely and it it will be seen that all the creatures are designed for aquatic life. The only creatures with limbs are the two ‘mermaids’ who have arms.

The following image is of the ceiling of this room. The numbering is to help locate the images described further on.

The ceiling of this room is extremely busy. A number of the features in the design look to be similar. The pairings have been identified by the matching coloured circles. This suggests they were made with the aid of a mould. However, each of the mythical or imaginary creatures – denoted by a number – appear unique. Would separate moulds have been made for each of these? Possibly, money doesn’t seem to have been a problem when Phase 1 of Eastgate House was commissioned. Another question – and why would each have such distinctive but still familial features? It would have been much easier to have one mould to make them all the same. This approach would also be less costly, rather like Sackville’s leopards.

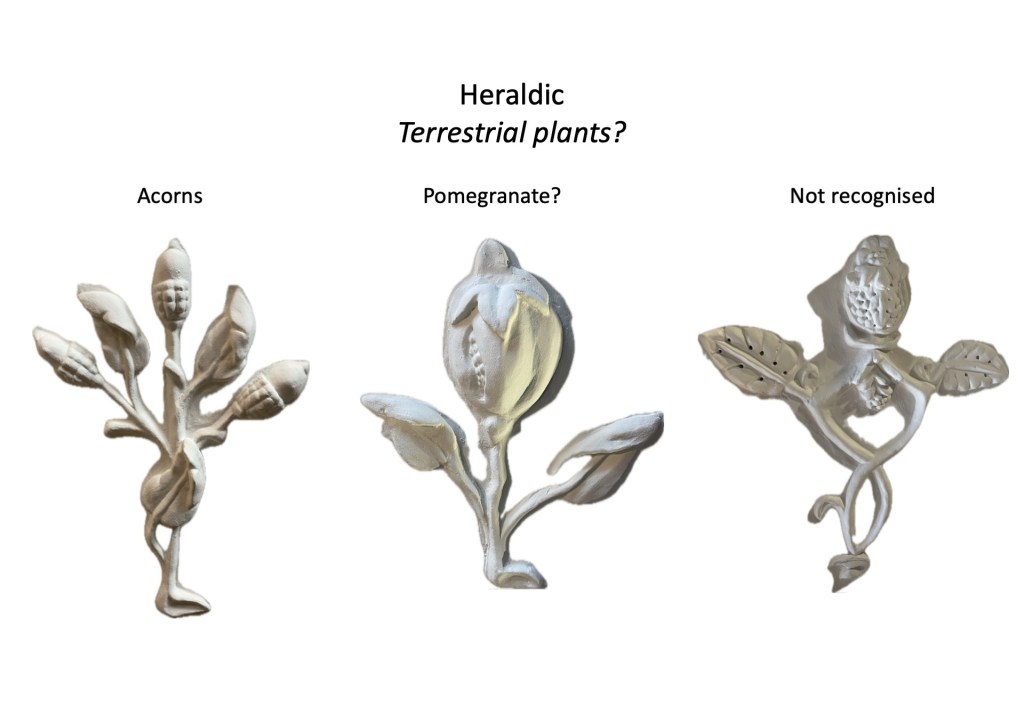

There are no heraldic devices in the design, but there are symbols used in heraldry; acorns to convey latent strength, and what could be a pomegranate symbolising unity and Christ’s suffering and the resurrection.

Other decorative features could represent aquatic plants or jellyfish.

It would appear a lot of effort and thought went into executing the design of this ceiling. This would be expected in the Tudor period when architecture and art was packed with symbolism. The symbols weren’t just decorative – they conveyed information to those who could read them.

The roses are included in designs confirming loyalty to the Tudor monarchy.

Cracking the Code – What could all this mean?

The following interpretations are ‘partially-informed’ suppositions. What is certain is the design is telling a story — but what could it be?

Central to the design in this room are two sea creatures. They appear to be fighting or frolicking. One of them is accompanied by a snake or serpent. This could indicate it is female because of the relationship between Eve and the serpent in the Bible. The serpent can also represent wisdom.

Both appear to be exhaling foliage. This is difficult to explain. Are they an aquatic version of dragon where breathing fire under water would be impractical? In folklore the Green Man can be depicted as having leaves growing out of his mouth and nostrils. He is regarded as a symbol of nature, fertility and rebirth. The jury is still out on what this symbolises – but could it represent the breathing of life?

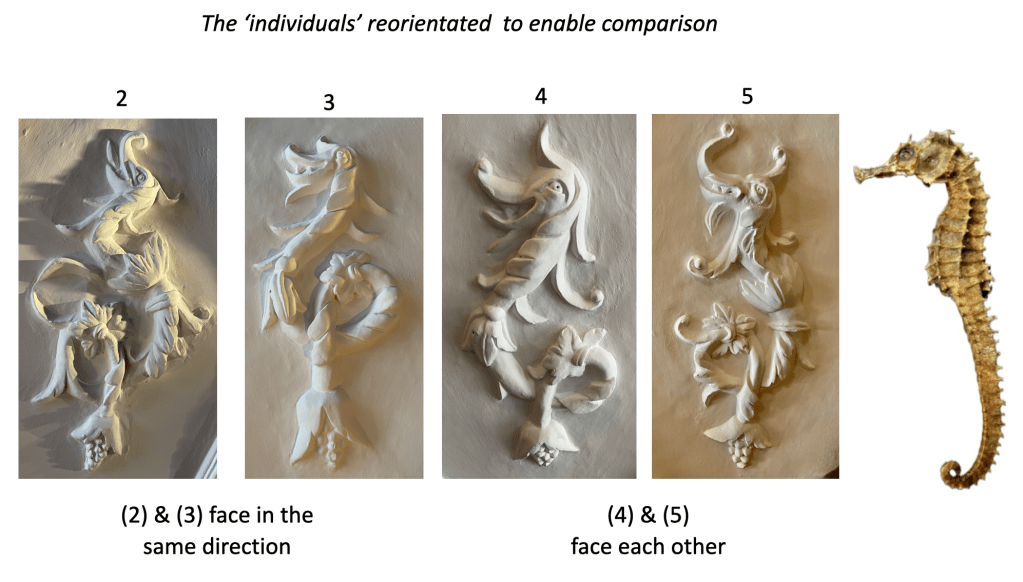

These central creatures are surrounded by four somewhat similar but ?playful? creatures. All six share some resemblance. The heads are not dissimilar and the four smaller creatures have berry-like terminus to their tails. The differences are such that they are more than minor modifications to a ‘standard mould’ suggesting they were individually crafted. It would have been so much cheaper to produce one mould. There must have therefore been some reasoning behind their designs.

The above images have been ‘cut & pasted’ in the position they appear in the design. Does one appear to be out of symmetry? Should (3) be facing (2), or should (4) be facing away from (5)?

Below they have been reorientated to enable comparison.

(5) and (2) have similarities in terms of their noses. They also have a crest on the top of their heads. Individuals (4) and (3) have similar shaped snouts. They both feature a double quiff on the back of their heads. Could these be representations of male and female? Could these be playful youngsters – with one being portrayed as mischievous? Could they represent children of the family? Your interpretation will be as good as mine!

Either side of the room, there are two merpeople. Close to the window is a merman typically holding a knife. The one, opposite, looks more female and may be a mermaid. It is also accompanied by two serpents further suggesting a female character imbibed with wisdom.

In Tudor times, mermaids held great significance in maritime culture and art — but of mixed blessings. Sometimes they could be seen as protectors and guides, but the can also be bad omens.

Mermaids are usually portrayed as vainly holding a mirror and combing their hair. In this depiction, the mermaid is holding something. However, it doesn’t look like a mirror. It looks very similar to the end of the tails of the central and surrounding creatures. The other hand that’s normally shown as holding a brush or comb is pointing. But at what? Could it be pointing in the direction of the Tudor dockyard at Chatham?

In some mythology, mermaids are believed to lure sailors onto the rocks. Could this depiction be of a mermaid luring the Spanish towards their defeat by the English navy based at Chatham?

Artists of the time depicted England’s triumph over Spain using various elements. The inclusion of mermaids in the ceiling design of this room would have perfectly aligned with this artistic trend.

Could the central ‘creatures’ be stylised dolphins?

There is a resemblance to seahorses which were used in Tudor art as a nautical symbol. However, those in the ceiling’s design also closely approximate to drawings of dolphins from the late 16th century. It is possible that these creatures could be stylised dolphins? The similarity between them and other portrayals known to be dolphins, is marked. The Eastgate plasterer/artist may have never seen a dolphin and could have used illustrations of the time for reference.

The above images show the dolphin with a curved snout. Another image shows a dolphin with a ‘berry tail’. These features are very similar to those in this ceiling.

Dolphins have great significance in maritime mythology. They were often used to decorate Tudor warships and weaponry. Because of their playful nature and intelligence, dolphins were used to symbolise friendship between man and sea. They were also used as a good omen for safety at sea. In short, they could be regarded as being masters of the sea.

Sir John Hawkins — a man with Chatham connections— had dolphins as supporters on his coat of arms. He received this honour after he was knighted in 1588. This was for his involvement in the defeat of the Spanish Armada that year.

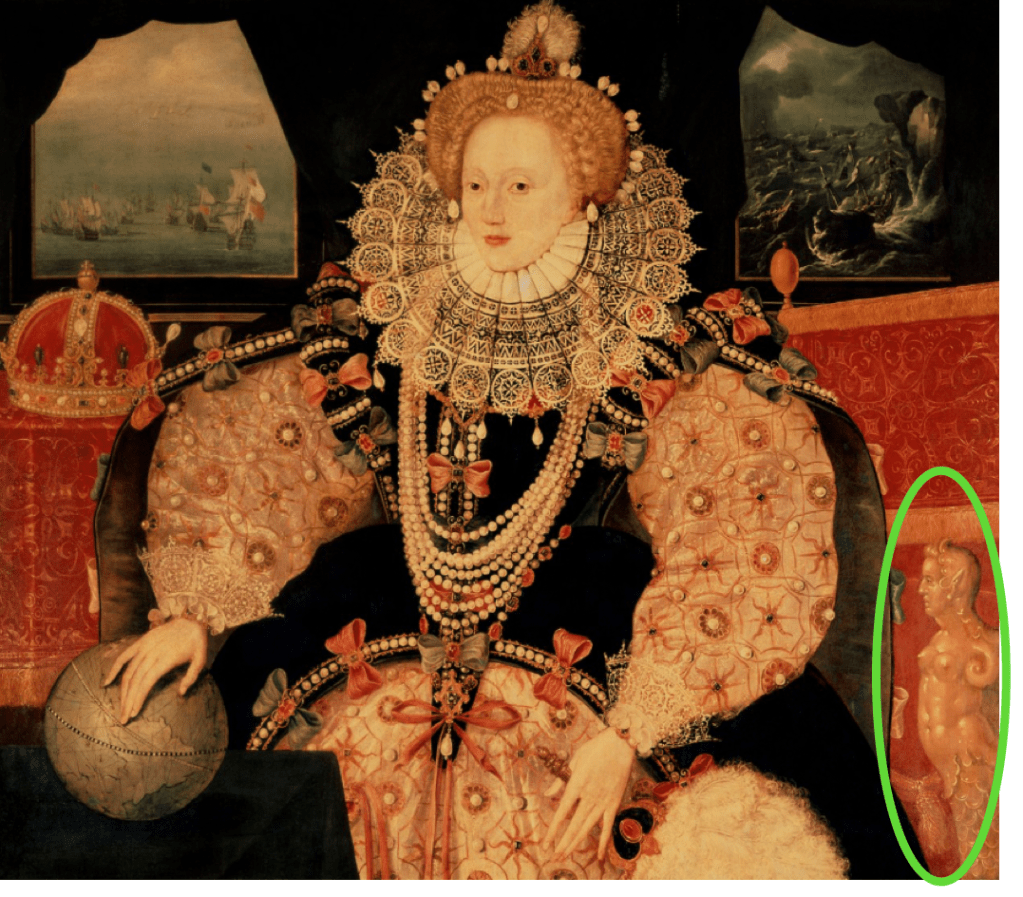

Speculative thought – could the ceiling be depicting the defeat of the Spanish Armada? During Elizabeth I’s reign, the use of propaganda was prevalent. Elizabeth recognised that portraits could also be used to subliminally express religious Protestant messages, and convey the strengths of a female monarch.

The defeat of the Spanish Armada was a tuning point in English maritime history – militarily and commercially.

A turning point in English Maritime History

The Spanish were defeated two years before construction of Eastgate House commenced. This victory heralded a new era in England’s naval prowess. This period also saw dolphins being used in art and pageantry to signify England’s new self-confidence as a seafaring power — mastery over the seas?

One portrait of Elizabeth I painted after the defeat of the Spanish (c.1590) is full of storytelling and symbolism. The image to the right of Elizabeth show rough seas and the Spanish fleet in disarray. The one to the left shows a calm English fleet. There is also the symbolism of a mermaid carved into her throne. Some art critics suggest this represents female wiles that lured sailors to their doom. Some suggest it symbolizes the Queen’s defeat of the Spanish Armada. Others believe it highlights her command over the seas.

A speculative interpretation of the Marine Room ceiling.

Could the central figures of the ceiling be representative of the tussle between Elizabeth I and Philip of Spain? One has an associated serpent. Could this indicate Elizabeth?

Serpents were included in pictures of Elizabeth I. They are not necessarily used to deflect a female – there are many images of men being depicted with serpents. They were though used to convey particular qualities such as wisdom and prudence; the latter being regarded as a female quality in Tudor times. Conservators at the National Portrait Gallery, using x-rays, found that in a portrait of Elizabeth I c.1580s, she was originally painted holding a serpent. It was later painted over with a posy. In another painted around the same time, she is clearly shown holding a coiled snake. (BBC News Channel 4 March 2010).

Based on what is known of how Elizabeth I used art and Tudor iconography, the central feature of this ceiling could support an interpretation of the beasts representing the battle between Elizabeth I and Philip of Spain.

The Creature’s Exhalations

The designer of the ceiling in the Marine Room clearly wanted the central creatures to be exhaling something. Although I see leaves, could it be emblematic of wind, emphasised by leaves being blown?

Wind played a role in the defeat of the Spanish Armada. First, it was used to send fireships in the direction of the anchored Spanish fleet. Secondly and more significantly, a storm destroyed much of the Spanish fleet whilst it was returning to Spain via Scotland and Ireland.

Circulating Smaller Creatures

If not the features, the ceiling’s designer must have given thought to breaking the symmetry. All four of the smaller creatures have their tails pointing at each other, suggesting a semblance of symmetry. But when it comes to their heads, two are facing in the same direction, and the other pair facing each other. Could they represent ships?

Tudor artists often used ships, and sometimes sea creatures as allegorical symbols of a nation. The “Armada Maps” drawn in 1590 showed the defeat. The map included marine monsters. These apparently conveyed the untamed natural world brought to order by the English – chaos vanquished.

If the smaller creatures are representations of dolphins, that would also fit with the narrative of the defeat of the Armada, and England’s emergence as a maritime nation. In art, dolphins have been used to symbolise divine protection and guidance.

Total speculation, but could the story being told in the design of the ceiling of this room relate to the defeat of the Spanish and celebrating England’s emergence as a maritime power? All attributed to God favouring Protestants.

A turning point in Peter Buck’s career?

Peter Buck likely played a role in preparing some of the ships that engaged with the Armada. Some of these had a Chatham connection.

The Ark Royal – launched at Deptford in 1587 and refitted at Chatham.

Revenge – built at Deptford 1577, maintained at Chatham. This ship was commanded by Sir Francis Drake when the Amanda was engaged.

Triumph – launched in 1561 and based and overhauled at Chatham during the war with Spain. It was Elizabeth l’s largest ship.

Swiftsure – launched at Deptford in 1573, stationed at Chatham.

Dreadnaught – launched at Deptford in 1573 and refitted at Chatham. It was in the front line of the endangerment with the Armada.

Peter Buck was not involved in the battle. However, he would have undoubtedly shared in the joy and jubilation of the success of the English fleet. He would have also benefited from the ‘reflective glory’ and increased trading opportunities. Could the design of this ceiling have been inspired by the defeat of the Spanish Armada?

The following is total speculation – based on what I might have done!

Today we display family photos in our personal space. These are often of family members and their achievements. This means was not available to the Bucks. However, I suspect their sense of pride would have been no different to what we experience today.

Could the central creatures represent Peter Buck and his second wife, Mary? There is little to distinguish between one being male and the other female, other than a serpent associated with one. In symbolism, snakes are associated with females (Eve) and wisdom.

When construction of Eastgate House began in 1590, Peter Buck had two older children by his first wife, Margaret. They were Peter Buck jr., aged 24, and Elizabeth, aged 22. Peter Buck had nine further children with his second wife, Mary – six sons and three daughters. (Dates of birth unknown.) (Buck Family and Eastgate House published by the Friends of Eastgate House.) Peter Buck’s first wife died c. 1580. It is not known when he married Mary. However, there would have been time in the intervening ten years for him to start a new family with her.

Could therefore the two merperons be representative of Peter Buck’s older children, and the smaller creatures his new family? If this were to be so, could the ‘circulating’ smaller individuals / ‘baby dolphins’ represent their playful children?

A Celebration of Naval Success and Family Joy?

In summary, was the ceiling design inspired by the defeat of the Spanish Armada? Was it installed to celebrate England’s naval prowess? If the room below this one was Peter Buck’s study, the upper rooms would have been private. What better way to make the ceiling more personal than by having the family ‘cast’ in particular roles?

This interpretation is entirely speculative. Others may have a different explanation or interpretation. But whatever, there was a story in the mind of the persons who designed and constructed this ceiling.

Moving on from the ‘Marine Room’ to the ‘Family Room’

The Family Room

This room is designated as the ‘Conservation Room’ by the curators at Eastgate House.

Through the centre of the room there are three coats of arms included in the design of this ceiling.

Over the fireplace is that of the Bucks, and over the window that of the Creswells. This is the only room to display the coat of arms of Mary’s family. In the middle of the room is an impaled coat of arms – an amalgamation of those of the Bucks and the Creswells. However, it has been created wrongly. The craftsman may not have understood the convention. Alternatively, it could have been an error on ‘transcription’? The ‘right’ of a mould would be come the ‘left’ when the moulding is stuck or impressed onto the ceiling.

The coat of arms of the male line has been placed on the right. However, the Collage of Heraldry describes a design from the perspective of the person holding the shield. This depiction is from the viewer’s perspective and therefore the wrong way round. The impaled shield in the ceiling of the Heraldic Room is correct. Could this, along with the differing styling, suggest the ceiling of each room was crafted by a different person?

Surrounding the family crests are four pairs of ‘creatures’. These seem very oversize for the room. Over the entrance to the room are a pair of deer, which appear to have male genitalia. This is probably a pun on the name of buck — a term used for male fallow deer.

Diagonally opposite are a pair of rampant (standing upright, fore-paws raised) male lions. Lions, as the king of the beasts, are used in heraldry to denote bravery, and their standing position denotes a readiness for combat. Lions can also represent guardianship.

The other side of the fireplace are two mythical sea creatures. Their heads and tails have some similarities with the central creatures to be found in the Marine Room. These, however, have ‘arms’. They also appear to have cloven feet, like the deer. These look much like stylised seahorses.

The head is horse-like and the tail aquatic. This would not be irrelevant in the design of this ceiling if it portrays a family story. In heraldry seahorses appear in heraldic designs for families connected with the maritime trade. Peter Buck’s family came from Southampton which had a significant port in the Tudor period, and his work was associated with the sea.

Below, the illustration to the right is from the coat of arms of Worshipful Company of Pewterers (City of London). It was awarded around 1570.

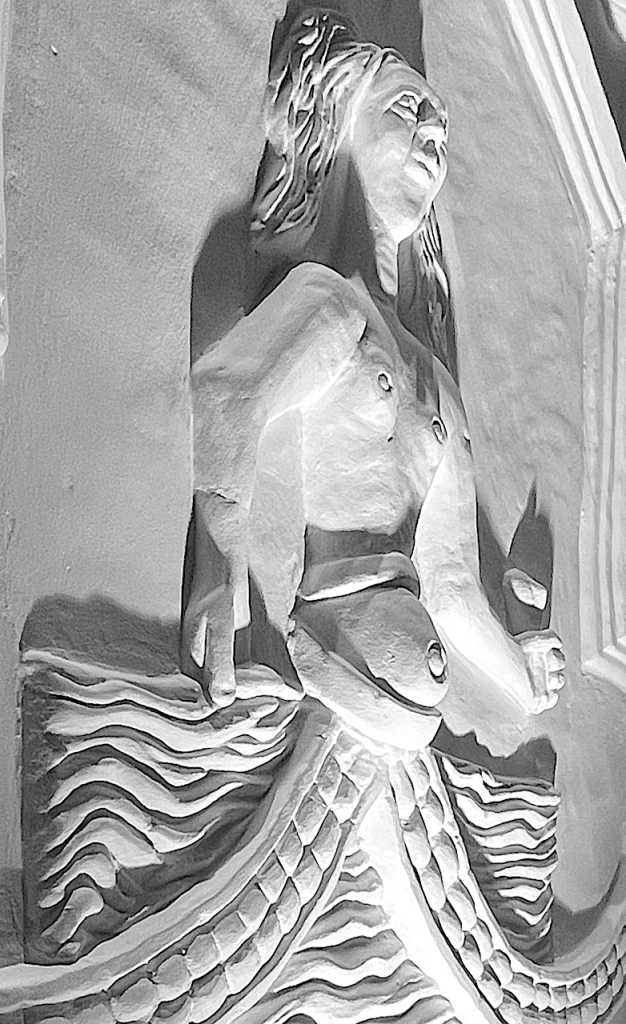

Diagonally opposite these ‘creatures’ are a pair of merpeople or melusine – a common image in European folklore. Melusine have two tails and generally are male. One of the pair though does appear to be female.

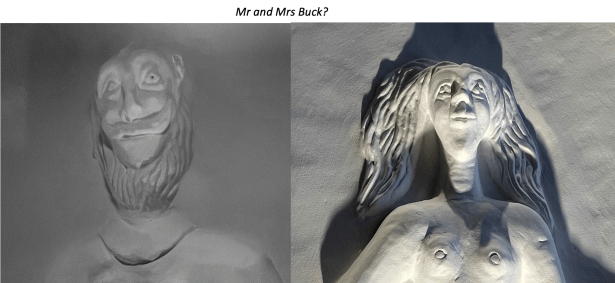

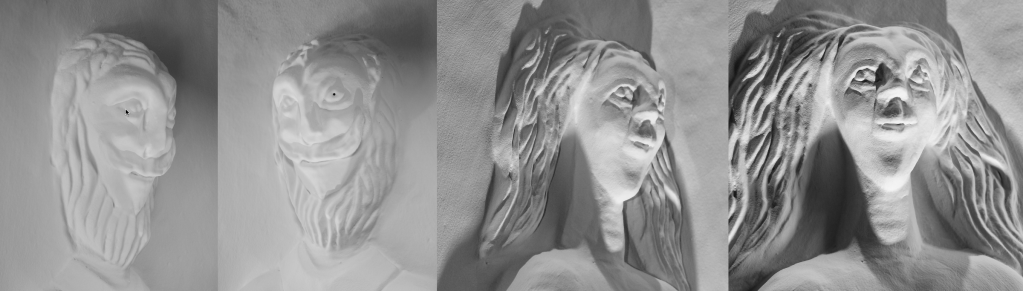

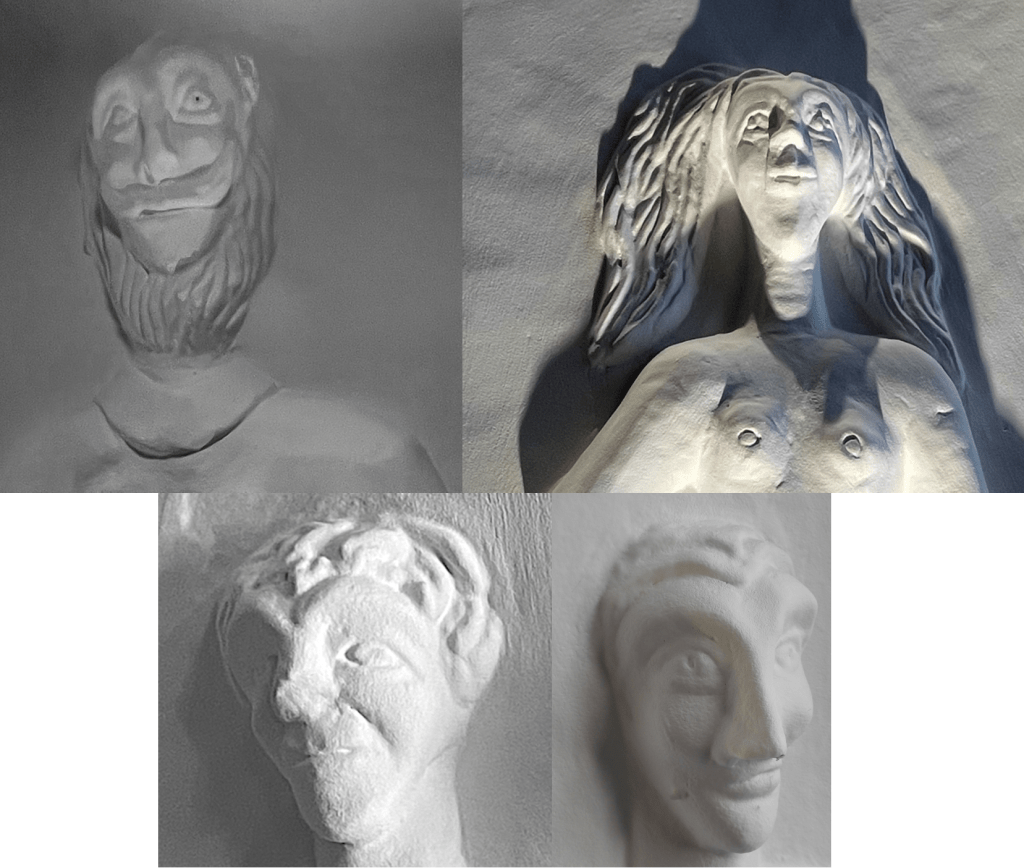

Could the faces of these melusine’s have been modelled in the image of Peter & Mary Buck? The male face is that of a middle-aged man, and could the female be pregnant? Her belly looks swollen.

Peter Buck would have been in his 40s when Eastgate House was started. The head depicted is of a moustached and bearded man with a receding hairline.

Mary could have been in her early 30s. She had many pregnancies. I therefore wonder if the family story is contained in the modelling of this ceiling? Family history is told with the family crests and the deer being a rebus / pun on the name of Buck. There is a nautical connection, and could the ‘pregnant’ melusine be a nod to the couples growing family?

This is explored further in my blog – Mr & Mrs Buck?

A Family Portrait?

The following image places a portrait of Sir John Hawkins (c. 1597 and 1601 beside the face crafted in the ceiling. Clearly not the same person but there are similarities in ‘style’ – perhaps reflective of the time? Both show a beard and moustache combination with a somewhat pointed chin. They both appear to be wearing a ruff. This could further point to the images to be found in the ceiling being more than ‘a random or ‘imaginative’.

Is it possible that all the older members of the family are part of the design of the second floor ceilings?

The faces of the merpeople in both rooms look quite distinctively different. This raises the possibility that the faces could have been crafted with individuals in mind. Had I commissioned these ceilings – before photos – I would have liked to see family members depicted.

Final thoughts

It was not unusual for artists to include familiar faces in their art. They often depicted family members, their patrons, or acquaintances. We do not know how good any representation of a family member could have been. However, the faces of the merpeople included in the second-floor ceilings are all very distinctive from each other, and could be recognisable to those who knew them. So maybe?

My sense though – compared to the ceilings seen elsewhere – that those at Eastgate House are somewhat amateurish. In the stately homes the ceilings have finely crafted features. Those at Eastgate House lack finesse – perhaps a classic example of where less could have been more.

Having made that observation – I’m sure the ceilings contain a coded-story far more complex than those of Knole Palace. I’m also happy to speculate that the ceilings on the second floor tells something of “Mr & Mrs Buck” celebrating the setting up of a family home and their family(s). Further they may also have been celebrating some good fortune that came with the defeat of the Spanish Amanda.

Whatever you feel or believe, do ‘look beyond looking’ and ‘see what you can see’. If there is a right answer, we do not know it – so why not let yours and your children’s imaginations create a narrative of their own? Want it included at the end of the blog? Then send it to geoff.rambler@me.com

Geoff Ettridge aka Geoff Rambler

13 September 2025. Updated 7 October 2025

For more information about ornate plaster work visit the website British Renaissance Plasterwork by Dr Claire Gapper.

Comments are closed.