Pedestrianism – Craze, Con, Scam? – 1815

A combination of poverty, hardship and the drive for celebrity, exploited the poor – back then, as can happen today. This is an account of when Pedestrianism reached Rochester when people were paid to undertake arduous walking challenges for the wealthy to bet on. For the early achievers there was the promise of ‘celebrity’ and larger fees to undertake increasing arduous ‘walks’. It also provided an opportunity for ‘scammers’ and betting cheats.

Rochester – “fashionable scene of pedestrian amusement” (1815)

Today individuals undertake endurance challenges to raise money for deserving causes. In the past such challenges presented a commercial opportunity and a way out for some from an impoverished situation. Rather than being sponsored by altruistic businesses these challenges were often ‘funded’ by the betting fraternity – or perhaps pub landlords.

A way out of Poverty?

By the late 18th century, the country’s Poor Laws were creaking under considerable pressure. Wages were low, the cost of bread was high, and even the able-bodied were often unable to find work, or work that paid sufficient to support their family. Unable to ‘get on their bike’ – as Norman Tebbit implied the unemployed could do – many metaphorically put on their ‘walking boots’ and joined the ‘craze’ known as Pedestrianism.

Pedestrians & Pedestrianism

The undertaking of endurance challenges for a fee appeared in the early 19th century. These involved people walking incredible distances within diminishing timeframes. The early challenges involved walking 1,000 miles within 21 days. Later the distances became longer, and women & children became involved in undertaking walking challenges. Those undertaking such challenges were referred to as ‘Pedestrians’, and the fad became known as ‘Pedestrianism’.

In September 1815 a man by the name of George Wilson had attempted to walk 1,000 miles in 21 days on Blackheath, London. It attracted considerable press interest as well from punters betting on a particular outcome. Wilson failed in the challenge – probably as a consequence of interference by those who disagreed with such challenges or by those who may have had a financial interest in him failing.

Pedestrianism arrives in Kent Via Rochester

Presumably spotting a business opportunity Mr Howes, the landlord of the Cossack Public House at the Delce, Rochester, decided to promote similar challenges.1 In October 1815 he laid out a one-furlong (220yd) track on Cossack Field that was opposite his pub. It was a linear course that would need to be walked eight times / mile or 8,000 times to achieve 1,000 miles. This design of track was regarded as being more challenging than a circular course used by Wilson as the Pedestrian would need to lose rhythm as they changed direction at each end. This less-than-ideal layout was probably due to the gradient of the field which would have made walking a circular course more arduous.

The track was laid out on level turf and encircled with a cord. There was a seat at one end and a British flag at the other. Howe then invited people to take on the challenge. It would appear that he charged a fee for use of his track as one potential challenger risked loosing a sizeable deposit if he did not commence his attempt within a specified time frame; perhaps £10, the equivalent of £750 today.

Howes would also have made money from providing facilities for the Pedestrian and from presumably selling refreshments to spectators.

Mayor gives his approval – and deploys Constables

In order to avoid the disruption that Wilson experienced, Howes obtained the approval of the Mayor of Rochester. On giving his approval the mayor directed that constables would be present to prevent any interference.

Let the Challenges begin

Two attempts were made to walk 1,000 miles in 21 days during October / November 1815, on the track laid out by Howes. The question needs to be asked why during these months – the months known to be the wettest of the year (A). As Wilson had failed his challenge in September 1815 I wonder if Howes was trying to ‘steal a march’ on others thinking of putting on a similar event in Rochester or Kent – possibly Maidstone as very soon after a track was marked out on Penenden Heath.

The language used in news reports of the two attempts show how ‘class-riven’ Rochester / Medway was in the 19th century.

It was clear from news reports that the preparations made by Howes, in respect of the track and the management of the event, were possibly made in haste. Wilson undertook his challenge on a one-mile circuit in the dryer month of September; consequently this track would not have taken such a foot-pounding as the short linear track of Howes. Similarly, the preparations made by the first of Rochester’s Pedestrians – were far from adequate in terms of clothing and support.2

Challenger One

The first Pedestrian was William Tuffee / Tuffy who was described as a friend of the landlord of the Cossack public house. The press reported that for undertaking the “laborious task” of walking 1,000 miles in 21 days, he was paid 50 guineas – about £4,000 at today’s rate.3

Tuffee was a baker by trade from Delce Lane, St. Margarets, but worked as “a farmer’s servant” – “which [had] been his principal employment through life”. He was around 34/37 years of age, about 5’ 8” tall, married with five children, and lived opposite Cossack Field.4,5

Tuffee’s preparation for the challenge was no more than his usual practice of walking to work – a round trip of 32 miles.6 It also quickly became obvious that Tuffee’s kit was not up to the task or the “tempestuous weather” that he was to face; further he lacked a support team.

Tuffee’s Attempt

Tuffee started his challenge at 5am on 15 October 18157 – the day that Napoleon entered exile on St. Helena. His usual walking-day started in the early hours sometime between 3 & 4am – and ended when he had completed 50 miles, which could be late into the evening – sometimes 10pm.

The weather quickly turned against Tuffee. The ground became waterlogged and rapidly became very slippery – the impact on the ground being exacerbated by the short to & fro track. The soles of his boots also offered him no grip and this slowed his pace. In order to improve conditions ash was brought in and spread on the track. The lack of team-support also meant that Tuffee was not adequately nourished. The combination of the conditions and poor nutrition quickly led to Tuffee becoming fatigued.

Soon more money was being placed on Tuffee failing the challenge. Perhaps recognising that the lack of support and appropriate clothing, could undermine any chance of success – “several Gentlemen of Rochester” / “men of distinction”, who may have had a financial interest in him succeeding, organised themselves into a committee to provide Tuffee with better nourishment and other assistance.8 They also arranged for him to spend a night at home rather than in the Cossack. Having spent a night in his own bed it was reported that he had had the best sleep since the commencement of the challenge. (Interesting that ‘they’ arranged rather than Tuffee choosing to spend the night in his own bed. How much of a free agent was he?)

Weather turns a Challenge into an Herculean task

Unremitting “Torrents of rain” added to Tuffee’s woes. Apart from the waterlogged ground, his progress was also hampered by having to wear a heavy greatcoat (B) and carrying an umbrella.9 He also sustained an injury to his leg caused by some “unfeeling people” placing impediments in the road he had to cross between the course and the pub.10

The fund set up to “properly equip” Tuffee was not well supported as very few were turning up to watch the challenge – because of the weather? This would have detrimentally impacted on Tuffee’s morale and the profitability of the event – both for Howe and ‘book-makers’. Sufficient funds though were raised to provide Tuffee with a flannel jacket, pegged shoes, and Madeira & tobacco for fortification etc. A tent was also provided for his comfort at one end of the course by his friend, Mr Howe.11

People of the “first respectability” come out in support

On Day 8 (Sunday 22 October) word of Tuffee’s challenge had reached across Medway with the consequence that “Rochester exhibited a greater scene of bustle” than could be remembered for some time. People in their thousands turned out to support Tuffee in his “Herculean task”; they came from Chatham, Brompton and Strood and the adjacent neighbourhood – “the greater part of which were of the first respectability, beauty and fashion”.12 News reports of this visitation also made mention of the constables who were present to protect Tuffee from insults and impediments – which may have come as a consequence of him walking during Devine Services on Sunday.

Despite the provision of better equipment and food Tuffee continued to experience extreme fatigue – “it is presumed no human being ever had a harder task than Tuffee”.13 On the freely given advice of Mr/Dr Newson, surgeon from Rochester, Tuffee was placed in a warm bath before going to bed. When he arose he was stiff and his feet pained him; he had also reported severe rheumatic pain in his hip / knee – no doubt exacerbated by the slippery ground and now walking with shoes with nails through the soles. Tuffee considered relinquishing the challenge but was persuaded to continue.

On Day 10 Tuffee only managed to walk 25 miles due to rheumatic pain in his right knee. He was though hopeful that he could make up for the lost time. However, by Day 13 and having walked 553 miles, it was clear that there was no prospect of him completing the challenge – much due to the state of the course14 which it was reported had caused him “severe rheumatic pain”15, so he threw in the towel. In the same reports of Tuffee’s withdrawal the press was heralding a new challenger.

Lessons had been leant

Better arrangements were put in place for the second challenger – perhaps as a consequence of the involvement of the “Gentleman of the Cossack Cricket Club” (C).16 The arrangements included the construction of a bridge of sorts, of boards between the track and a pair of steps that led to a window in the Cossack public house. This opened into a small room in which the Pedestrian could rest, take refreshments and sleep – for which a sofa had been provided. (During Tuffee’s challenge he sometimes had trouble crossing the road and on one occasion injured his leg.)

Investment had also been made into providing better facilities and amusements for spectators.

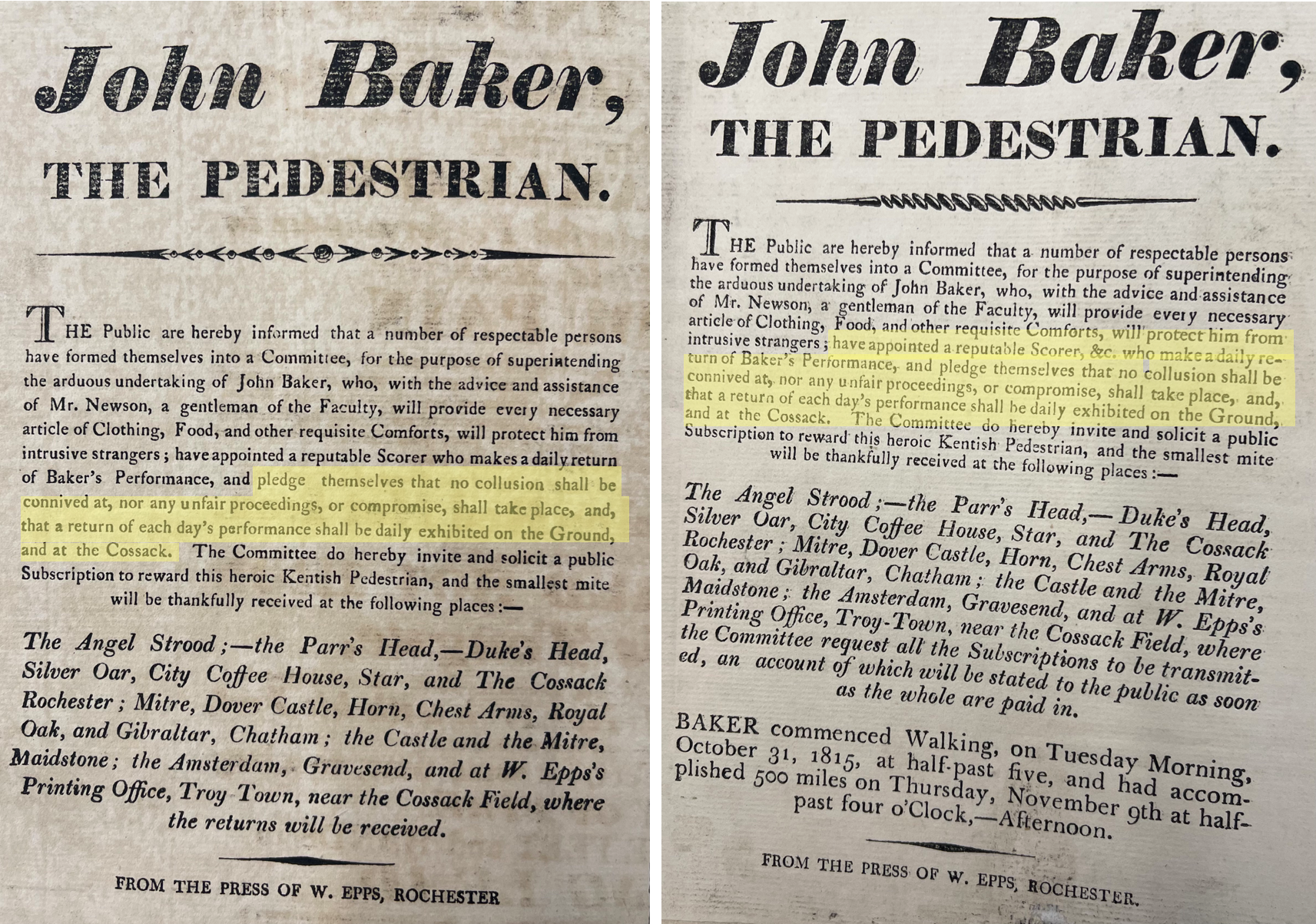

Notices were posted around Medway providing details of the challenge and how it was to be managed / overseen. Donations were also solicited to “reward [this] heroic Kentish Pedestrian”. These could be left with various public houses in Medway, Gravesend and Maidstone.17

Challenger Two for “Pedestrian Fame”

The second challenger was Jack/John Baker. He was required to start his attempt at walking 1,000 miles in 21 days within seven days of Tuffee ending his attempt. Because of the condition of the track Baker’s team looked for an alternative track – but that would have meant forfeiting the deposit paid to Mr Howes.18 I therefore suspect a fresh track on Cossack Field would have needed to have been created.

Baker came from Snodland and was reported to be no more than 27 years – about 10 years younger than Tuffee. On the day that Tuffee conceded Baker went into training under the guidance of Mr Newson, surgeon from Rochester, who again provided his services free of charge and “unremittingly throughout the challenge”19. (Could he have been part of the committee with a financial interest in the Rochester walking matches?)

It was reported that Baker was well accustomed to walking long distances as he was a smuggler who frequently walked between Dover and Rochester carrying a heavy load.20 It was also reported that he was a “Kentish trader” without any reference to what trade. Regardless of the truth of his background, betting was strong that he would achieve the challenge – before he had even taken a step! This supported the local belief that this “Grand Match” would attract the attention of the “sporting gentry” from every part of the country.21 (This could also explain why detailed reports of progress, physical condition, amount of sleep and nutrition etc., of the Pedestrians, appeared in papers across the country – like how the form of horses is reported?)

As before, the mayor’s approval was sought. Again, he agreed that officers would be deployed to keep the peace but stated that he would not have their support if he walked during the times of Divine Service on Sundays.22

The night before the start of the challenge Baker wagered that he could walk one mile in 10 minutes – this was accepted by a Mr Chalmers jun. a “respectable gentleman farmer”. Baker completed the mile in nine minutes23 (6.7mph) – during the actual challenge Baker walked at an average rate of 4.25mph.

Baker’s Attempt

Baker started his challenge at 5:30am on 31 October. He was accompanied to the starting post by Messrs. Chambers sen., and Epps, and the “Gentlemen of the Cossack Cricket Club” who loudly cheered him off. The ground was reported to be in good order, and the field was thronged with spectators throughout the day.24

Baker set off wearing a waterman’s flannel cap, a fustian (D) frock and trousers, and large half-boots that weighed 3.75lbs – despite friends earnestly requesting him to wear shoes; his wife even purchased a strong pair of shoes for him.25

Despite the poor weather, arrangements continued to be made in creating a fete like experience on Cossack Field.26

An Elephant adds to the ‘Attraction’

During Day 2 Baker lost time due to having to wait for a wagon containing an eight-ton elephant to cross the track to take up its station on the field.

Who supplied the elephant is not recorded but a “stupendous” performing elephant was kept at the Star Inn, Rochester – which was not far from Cossack Field. To view this elephant at the Star Inn cost 1s, half price for servants and children. It was though only five tons – not the reported eight tons – but then who had the means to accurately weigh an elephant!? (As a later report of a storm mentioned the booths around the elephant caravan were flattened, it therefore seems possible that Baker’s spectators may have had to pay if they wished to see the elephant.)

Other facilities added included amusements and a 100ft marquee27 to provide shelter for spectators – “who were mostly comprised of respectable people”. These additions, when the weather was fine, added to the merriment of the event28; this was in sharp contrast to the support Tuffee received.

An Attempted Nobbling?

Perhaps with it looking increasingly likely that Baker would succeed in the challenge, some “strangers” gained access into Baker’s accommodation in the Cossack. Here they tried to induce him to take some tablets and alcohol. He declined what was presented as performance-enhancers and reported the approach to the committee. The committee responded by placing a placard displayed on the door of Baker’s room stating that no person whatsoever could enter the room during the match unless they were known friends of Baker.29

Buoyed on by support

On Day 11 (10 Nov) Baker began to suffer from extreme pain that prevented him from walking his target distance that day. However a “powerful cathartic” administered by Mr Newson enabled him to continue. (The location of Baker’s pain was not reported but the treatment may have been an enema.)

The following day, buoyed on by a “vast concourse of spectators” Baker completed 50 miles30. The weather though continued to provide a challenge. On Day 14 (13 Dec) the weather was described as more “boisterous or “tempestuous” than even the oldest inhabitant of Rochester could recall – with windows being blown out at Rochester. Such was the strength of the wind, described in some reports as a hurricane, the spectators’ tent was totally destroyed, booths flattened, and the wagon housing the elephant was moved four inches31.

The benefit of having a support team

Bakers’ nutrition was well taken care of, and it is clear he was taking in the calories commensurate with his task. He would walk 15 miles before having a breakfast of toast and coffee. For lunch he had underdone beef-steaks or mutton chops, washed down with a little beer, and a glass or two of either port or sherry. Tea was taken in the afternoon, and his supper was similar to his lunch32.

‘Hero of Pedestrianism’

By Day 15 Baker had completed 750 miles and was being styled as the ‘Hero of Pedestrianism’ by his friends33. They were so sure of Baker’s ability to undertake endurance walking Mr Myers and Mr Chambers, jun., and two other gentlemen from Maidstone, offered a new wager. Baker was offered 500 guineas [£40,000] if he would walk 2,000 miles before any man in England – giving his opponent a 10 mile start; the challenge was to start in April or May 1816. Baker throwing up his hat up in the air, accepted the challenge on his terms stating – “Gentleman, God willing I shall be ready but must request the favour of having my present nurse, and be permitted to wear my own dress”34.

With the End in Sight

By Day 19 and ever more optimist of success, Baker was joined by fiddlers after he had completed his target of 50 miles. Buoyed on by this energy Baker walked and jigged a further mile – which he completed in 13.5 minutes – and then danced another horn-piper’s jig35.

Although Baker had 21 days to complete the challenge, he desired to enjoy the last day by completing his challenge in 20 days. With the approval of Mr Newton, it was agreed that on Day 20 (Sunday 19th Nov) Baker would walk 75 miles which would require walking through the night. Excitement grew during that day with Cossack Field exhibiting a “scene of gaiety never seen before”. It became extremely crowded with almost all descriptions of persons, among whom were Lord & Lady Torrington, Lord Clifton [Edward Bligh / Cobham Hall] and several others of nobility and gentry.

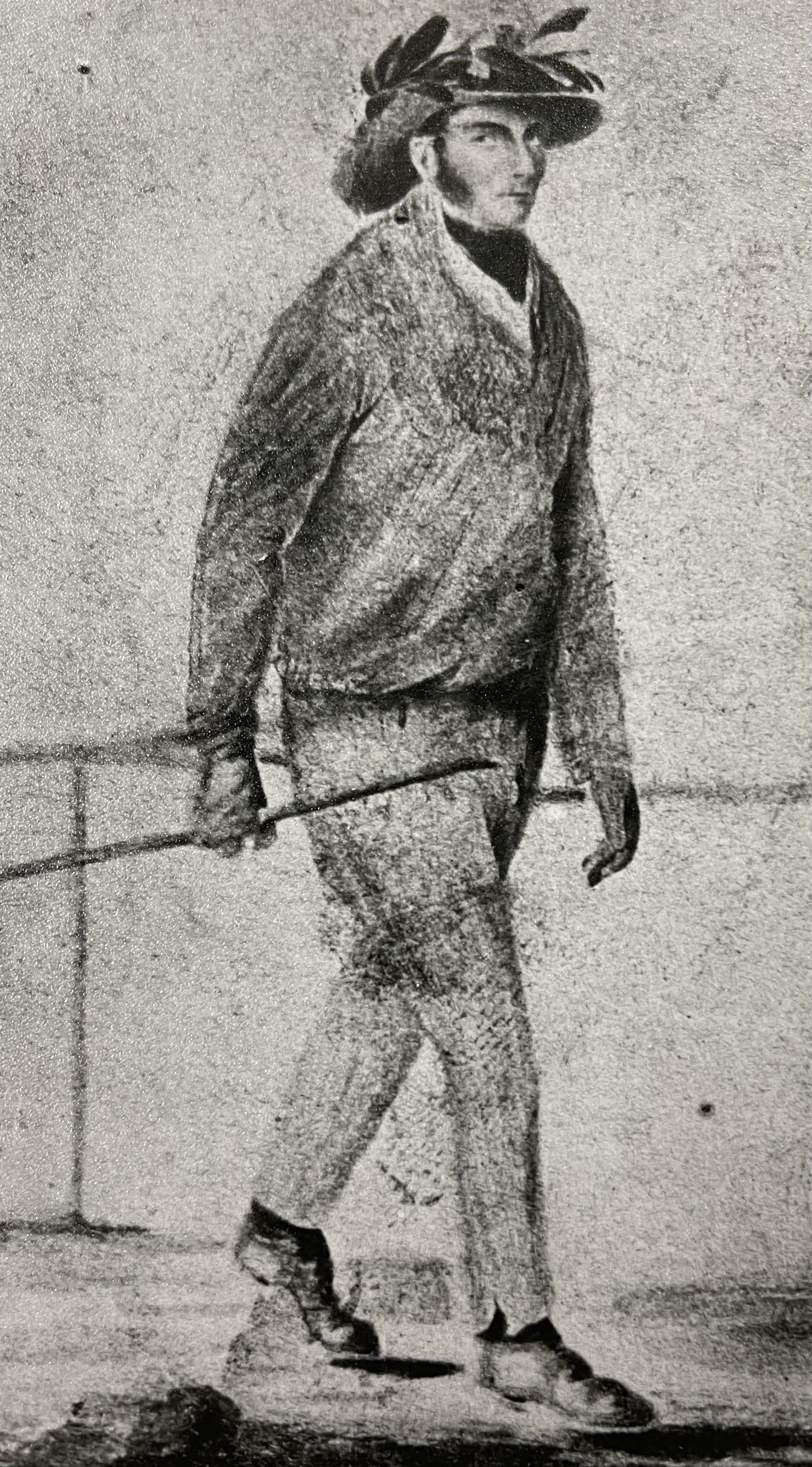

When Baker resumed his challenge having paused during the time of the Devine Service, he reappeared wearing a new white hat which was surrounded with wreaths of laurel and blue ribbons36. IMAGE

To ensure that Baker’s progress was not impended the mayor ordered his active officer, Davidson to be in waiting, with his attendants. To play to the crowd Baker would occasionally, during the day, complete a mile in 10.5 minutes37. (5.7mph)

During the night Baker was accompanied by four fiddlers and a tambourine.

On completing his target of 75 miles, and walking the 1,000 miles, Baker was joined by his wife Fanny – who he called “his little faithful rib” (E). She challenged him to walk a mile with her – a challenge he accepted and they went off side-by-side38. They completed the mile in 10.25 minutes (5.8mph!) On completing this he asked Fanny to do another with him – an invitation she declined!

Elephant Trumpets Success

Having completed the challenge + 1 at 4:55am on Day 2139,40, Baker retired to the Cossack amidst the acclamations of all present – including the roar of a huge elephant41.

Having rested Baker returned to the track at 10am on Day 21 to cheering from over 1,000, possibly 5,000, spectators. He was dressed in a white flannel jacket, a new hat but his old boots42. Some news reports stated he still had a few miles to walk to complete the challenge, however contemporaneous records held by Medway Archives show he had completed the distance before he retired.

Success Challenged!

Amidst the celebrations Baker heard that some were questioning whether he had completed the challenge as prescribed. The challenge was to walk the distance on the set track but Baker had also included the distance walked between the track and his room in the Cossack. To remove any doubt Baker walked a further nine miles accompanied by the Royal Marine band.

Victory Parade through Medway

In the afternoon Baker, his wife Fanny, one of his little boys, his nurse, Mr Howes, the landlord of the Cossack public house, the scorer and a few select friends, mounted a “fish-machine”(F) drawn by two horses. (NB: Baker started his walk wearing a waterman’s cap). Led by the Marine Band they headed to Troy Town. Here they stopped at the houses of some of the “Gentlemen of the Committee” before continuing to the home of Mr Newson the surgeon where the band played God Save the Queen.

The procession then passed through Rochester and thence to Strood halting at the home of Bakers friends and supporters; it then continued to Chatham before returning to St. Margaret’s and the Cossack public house. The streets and houses along the route thronged with spectators who cheerfully greeted Baker on completing his Herculean undertaking.

Baker becomes “a favourite of the fair sex” – and loses his hair

The day after completing his challenge Baker returned to Cossack Feld to help clear up. Word of this soon circulated and he was visited by several ladies and gentlemen who gave him gifts. Many women who were taken with ‘Baker, the Hero’, wanted locks of his hair. When his head was nearly cropped, he told the women they could only have more of his hair if they purchased him a wig – the ladies declined to take any more of his hair43.

Pedestrian Mania – “Betting on Walking Matches – One Fool Makes many”

A friend of Baker penned a few lines to mark his achievement – which also noted the mania that was developing of people undertaking ‘Walking Matches’ as a means of earning money – and perhaps fame44:

The fashion is a Walking Match,

But few can make it pay;

The Baker’s best of all the batch,

Who get their bread that way.

Across Kent other walking challenges of various permutations were arranged – presumably by pub landlords as many challenges seem to have a pub involved. Some of the challenges included women undertaking endurance walks. However, I’ve found no further references to walking challenges or matches being held on Cossack Field. This was probably due to the topography of the field which made it impossible to lay out a sizeable circular track on the level. This would have rendered it unsuitable for such challenges.

“Rage for Pedestrianism” 45

Based on the regularity of names appearing in the press around the country, it would seem that some men were making a living as ‘professional walkers’.

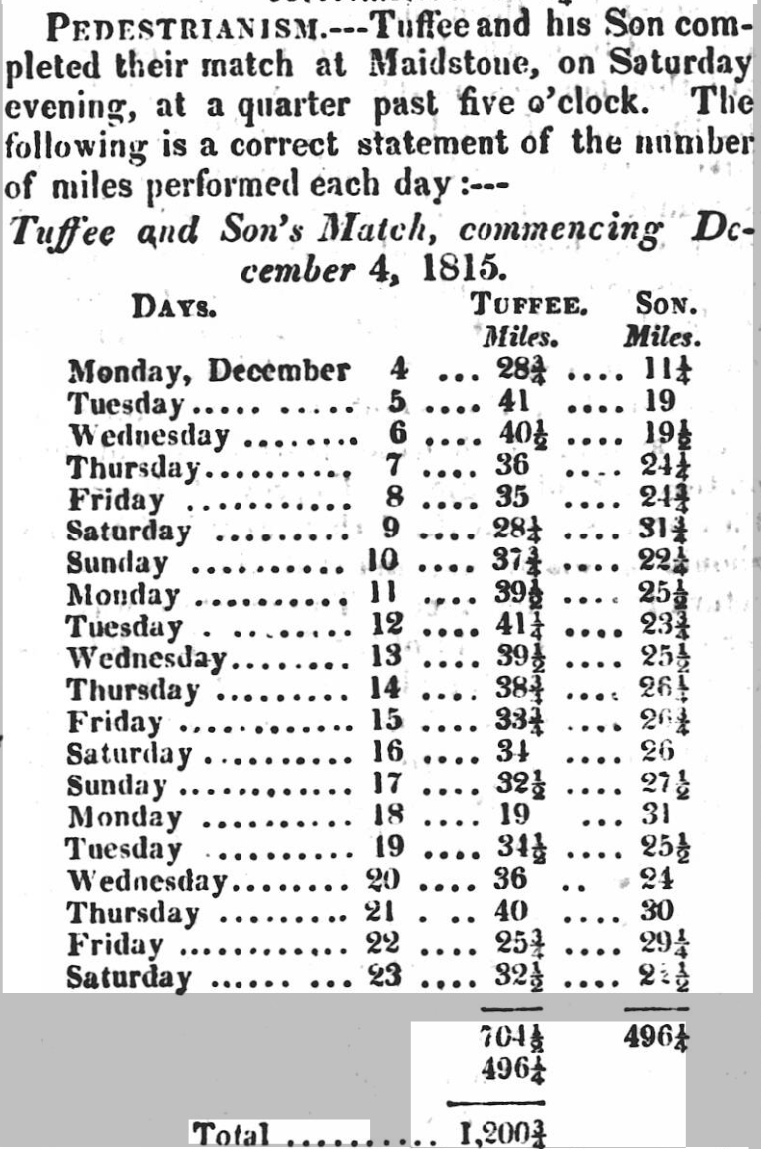

Tuffee on ending his challenge undertook another with his 12-year-old son46 on the ground of the Roebuck Inn at Maidstone. For 100 guineas [c£7,800] they undertook to walk 1,200 miles in 20 days – one walking whilst the other rested. The challenge started on December 4. Tuffee again suffered from inclement weather and the ground being ill prepared.47 They were successful with young Tuffe walking almost 500 or the 1200 miles, but with no accolade. They had been expecting a handsome subscription but this was not the case and they departed the ground of their performance almost unnoticed48; – perhaps there was insufficient jeopardy in the challenge to satisfy the appetite of punters, or did the public feel conned by what, comparatively, was not a very challenging challenge?

On the completion of the ‘Tuffee & Son’ challenge there was excitement that the challenge was to be taken up by a woman – Mary Frith – see below.

“Infantile Female Pedestrian” from Strood

One has to be mindful that the expectations placed on a child, and what was regarded as ‘childhood’, over 200 years ago, is widely different to today. As soon as a child was able to contribute to the family income they were expected to do so. However, could the use of the word ‘scarcely’, in the following, imply some criticism on the part of the journalist?

In 1823, Emma Matilda Freeman from Strood, “who was scarcely eight years old”, was challenged to walk 30 miles in 8.5hours49. She successfully completed this challenge with “apparent ease” despite heavy rain that fell for most of the day, on a circuit laid out on Penenden Heath – the place for public executions at this time. Emma went on to regularly undertake 30 mile walks in Kent and London – usually on a quarter-mile grass circuit for wagers of up to £100 – today the equivalent of approximately £10,000.

Miscellaneous other Kentish Challenges

Not all parts of the press were supportive of these challenges. When Baker took up the challenge following Tuffee’s attempt, some reported that “the repetition of these gambling tasks must disgust the public”50; but the appetite of the gamblers and pedestrians remained, and each successful challenge led to someone trying to eclipse it – across the country. Challenges became longer, faster or the challenger older.

The following are some of the walking challenges that were undertaken in Kent.

6 November 1815 (Chatham): For a £5 [c£375) wager with the Captain of a trading vessel, the owner of a donkey that was once owned by the celebrated Jack Hammond of Troy Town, undertook a 40 mile round trip between Chatham and Borden. The wager was that the trip could be completed within 12 hours – which it was51. [Nothing found re Jack Hammond.]

1 January 1816 (Maidstone): At the completion of the ‘Tuffee & Son’ challenge there was excitement that the challenge was to be taken up by a woman – Mary Frith. She started her challenge on 1 January and was backed for 30 guineas by three gentlemen, to walk 36 miles / day for 20 days in Roebuck Field. Other reports stated the challenge was to walk 600 miles in 20 days52. She was aged 36 and a mother of six and said to be familiar with hard labour often walking 20 to 25 miles / day travelling the county selling sundry articles – returning home at night53. Her freinds were “sanguine” about her completing the challenge.

No reports have been found concerning her progress or success54.

8 May 1816 (Wrotham): For a considerable (unspecified) wager Edward Millen undertook to walk 100 miles in 24 hours. A half-mile route was marked on the turnpike road near Wrotham, with the Royal Oak Inn being in the centre. The ground was very uneven and it rained almost continuously during the challenge. With 17 miles to go Millen was in great distress and betting came 3 to 2 against. He was allowed to rest but not receive any assistance to rise, but with a little Hartshorn [ammonia smelling salts] he completed the challenge with only six minutes to spare. He was carried to the Royal Oak where every attention was paid to him by the landlord, Mr Richardson. After a nights’ sleep Millen offered to walk 100 miles on the same ground with any man in England55. This led to a similar challenge but only faster.

3 June 1816 (West Farleigh): From the front of the Chequers in that village, David Holden set off to walk 100 miles but in 22 hours, on a piece of road 40 rods in length (one rod = 5.5yds; 320 rods to the mile). He was described as a ‘spare but muscular man’, and of very abstemious habits. Bets were 2:1 against him succeeding. After 14 hours and having walked 62 miles, he resigned56. (The Chequers is now known as the Tickled Trout.)

Press alert public that they could be being scammed

By the time that Baker had completed his challenge at Rochester parts of the press were highlighting the potential for the public being conned. The press was becoming aware that many were undertaking these challenges in pursuit of ‘Celebrity’ who were not up to the challenge and were making use of accomplices during the night.

Parts of the press began calling on the public to “discourage this ridiculous rage” which had become so common that every village was turning out a ‘hero’ – “‘paddling the hoof’ for glory and emolument”. The writer acknowledged that Baker attracted public interest but feared “that if this peripatetic propensity be much further encouraged, there is scarcely a porter, labourer, or jack-ass driver, that will not aspire to the glory of enrolling his name among the pedestrian worthies of the day.57”

Judging by the number of press reports it would appear that by the end of 1816 the people and/or the press had lost interest in Pedestrianism.

Contextual Information

The ‘header image’ of a man walking on muddy track, was created by AI – note it’s given the man an extra leg! AI was not used for anyother part of this blog.

A) Server Weather: It is possible that the weather was worse than that expected for the time of the year due to the eruption of Mount Tambora in April 1815 in what is known today as Indonesia. This is regarded as the most powerful eruption recorded. It lowered global temperatures and is believed to have been the cause of 1816 becoming known as ‘the year without a summer’.

B) Greatcoat: A coat designed for warmth and protection against the weather. They feature a collar that can be turned up and cuffs that can be turned down to protect the face and hands.

C) Gentlemen v Players: Cricket was initially the sport of the aristocracy. Many of whom engaged staff in order for them to play on their teams. For instance, John Sackville, 3rd Duke of Dorset, found jobs for handy cricketers who would then play for the ‘Knole’. The outcome of matches organised by the aristocracy provided an opportunity for betting. To distinguish between the amateur (aristocratic) players and those who were paid (staff), the amateurs were referred to as “Players” and the professionals were referred to as “Gentlemen”. Medway had many Gentlemen who played cricket. The distinction between amateur/player and professional/gentlemen started in 1806 and continued until 1963.

D) Fustian frock: Fustian was a heavy cloth woven from cotton and usually used to make work-clothing for men.

E) “Rib”: In the Old Testament (Genesis 2:22-24) it is stated God made Eve from a rib he took from Adam.

F) Fish Machine: This was a cart/carriage that was licensed under the Fish Carriage Act 1762, to sell fish in the markets of the Cities of London and Westminster. They were registered by the Land Carriage Fish Office. The law regulated the sale of fish in these markets – with stiff penalties for those who didn’t comply – including between one week and two months hard labour for some offences. A registered carriage had to be marked “FISH MACHINE ONLY”. The person who loaned the Fish Machine for John Bakers’ victory tour must therefore have been a local fishmonger who sold their fish in the city markets of London. (Sussex Advertiser – 26 April 1762.) At this time what we now refer to as Stage Coaches were referred to as Stage Machines – cf also Bathing Machines, no mechanism just an enclosed carriage.

Geoff Ettridge aka Geoff Rambler

18 September 2024

Sources – various newspaper reports of the time. Financial ‘equivalents’ calculated on the Bank of England Inflation Calculator. Contemporaneous material can be found in the PINN collection held by Medway Archives.

- Morning Post – 1 November 1815

- Pilot (London) 24 Oct. 1815

- Leicester Journal – 27 October 1815

- Kentish Gazette – 20 Oct. 1815; Windsor and Eton Express – 22 Oct. 1815

- Commercial Chronicle (London) – 24 October 1815

- Morning Post, 23 Oct 1815

- Leicester Journal, 27 Oct. 1815

- Globe, 24 Oct. 1815

- National Register (London) – 29 Oct. 1815

- Kentish Gazette – 24 Oct. 1815

- Statesman (London) – 21 Oct. 1815; Public Cause – 25 Oct. 1815; Bell’s Weekly Messenger – 22 Oct. 1815

- Norfolk Chronicle – 28 Oct. 1815

- Statesman (London) – 21 Oct.1815

- Exeter Flying Post – 2 November 1815

- Saint James’s Chronicle – 31 Oct. 1815

- Commercial Chronicle (London) – 2 Nov. 1815.

- Contemporaneous note held in the PINN book held by Medway Archives

- Star (London) – 24 Oct. 1815

- The National Register – 29 Oct 1815

- Morning Post – 1 Nov 1815

- Morning Post.- 31 Oct 1815

- Exeter Flying Post – 2 Nov. 1815

- London Courier and Evening Gazette – 31 Oct. 1815

- Kentish Gazette – 3 Nov. 1815

- Leicester Journal – 10 Nov. 1815

- Statesman (London) – 2 Nov. 1815

- Statesman (London) – 14 Nov. 1815; Morning Chronicle – 15 Nov. 1815

- Statesman (London) – 2 Nov. 1815

- Commercial Chronicle (London) – 7 Nov. 1815

- Kentish Gazette – 14 Nov. 1815

- Caledonian Mercury – 18 Nov. 1815

- Morning Post – 6 Nov. 1815

- Nottingham Review – 17 Nov. 1815

- Commercial Chronicle (London) – 18 Nov. 1815

- Leeds Intelligencer – 27 Nov. 1815

- Sun (London) – 20 Nov. 1815

- Stamford Mercury – 24 Nov. 1815

- Globe – 20 Nov. 1815

- Contemporaneous note held in the PINN book held by Medway Archives

- Oxford University & City Herald – 25 Nov. 1815

- Exeter Flying Post – 23 Nov. 1815

- Exeter Flying Post – 23 Nov. 1815

- Salisbury and Winchester Journal – 27 Nov. 1815

- Mirror of the Times – 25 Nov. 1815

- Saunders’s News-Letter – 21 Oct. 1817

- Caledonian Mercury – 27 Nov. 1815

- Saint James’s Chronicle – 5 Dec. 1815

- Kentish Weekly Post – 26 Dec. 1815

- Salisbury and Winchester Journal – 21 July 1823

- Bristol Times and Mirror – 4 Nov. 1815

- Star (London) – 7 Nov. 1815

- Morning Post – 1 Jan. 1816

- Morning Post – 12 Dec. 1815

- Morning Post – 12 Dec. 1815

- South Eastern Gazette – 14 May 1816

- South Eastern Gazette – 18 June 1816

- Durham County Advertiser – 25 Nov. 1815