This blog has had a significant update following the discovery of new documents. It was first posted June 2024

Let’s save a remarkable house of literature?

The restored and repurposed chalet could be used to inspire future generations of writers and storytellers. It could also add to the tourist economy at Rochester, that has been slowly depleting over recent years.

____________

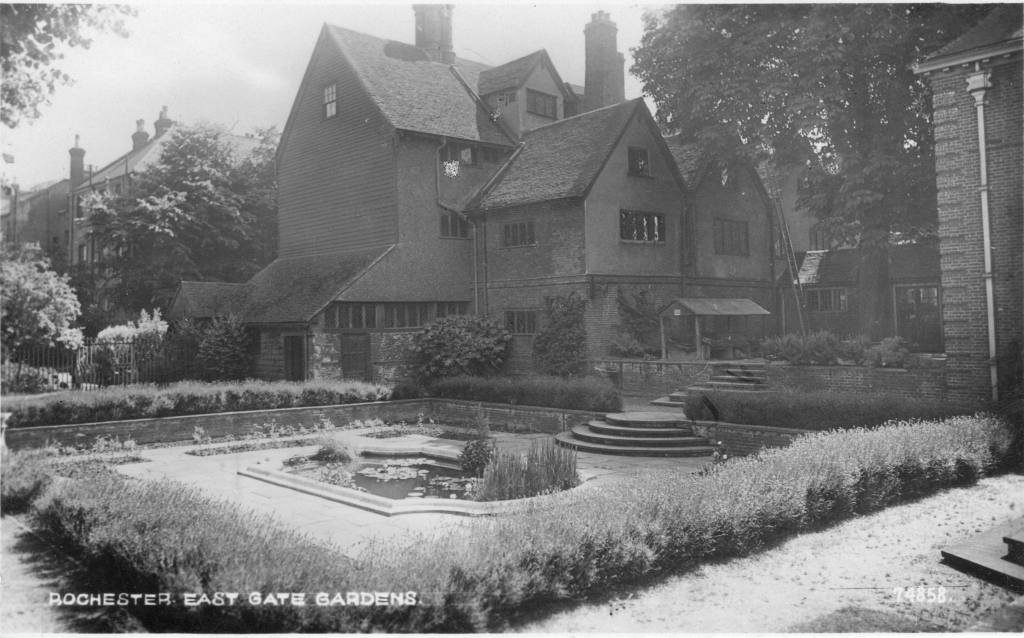

Charles Dickens writing chalet is situated in the grounds of Eastgate House at Rochester. It is currently on ‘life-support’ following decades of neglect. Is it time to get proportional and realistic in order to save it?

Voltaire is credited with saying “perfect is the enemy of good”. Sir Winston Churchill is said to have said that “perfection is the enemy of progress.”

Had Lord Darnley in the 1920s been more realistic about the cost/benefits/liabilities associated with the chalet, it may have been possible to have saved it. He was, though, expecting to find a buyer prepared to pay over £1m at today’s prices.

More recently, the Council has brought forward restoration proposals costing c£1m. All of which have failed. Another funding application (2025) is currently under consideration.

Let’s get realistic:

- The chalet was only used by Charles Dickens for five years.

- The only significant work produced in the chalet was part of ‘The Mystery of Edwin Drood’.

- The chalet has been reassembled six or seven times and had one significant restoration.

- The current structure is probably much changed from the prefabricated chalet received by Charles Dickens.

- The chalet is a softwood construction that can be easily attached by nature.

- Is it therefore practical and affordable to try and achieve ‘perfection’ if perfection cannot be described? Would it be more realistic to undertake a phased preservation rather than restoration?

- Funding could then be incrementally raised. Further potential funders would probably prefer not to put an amount into ‘a pot’. They are more likely to be attracted to funding an identifiable part of a project. This brings benefits to them—be that a business or charity that would prefer to be associated with something specific.

The following probably provides the

most comprehensive history of the chalet to be found

in print or on the internet

“One of the most remarkable houses of literature” or a Victorian Prefab?

“Miracle of Survival that is Dickens Chalet” – Chatham News 6 Aug. 1965

- Charles Dickens’ writing Chalet has been saved for the nation on several occasions.

- The auctioneer selling Dickens’ estate (1870) refused to sell the Chalet separate from Gads Hill Place, to deter American buyers and the loss of the Chalet to the nation.

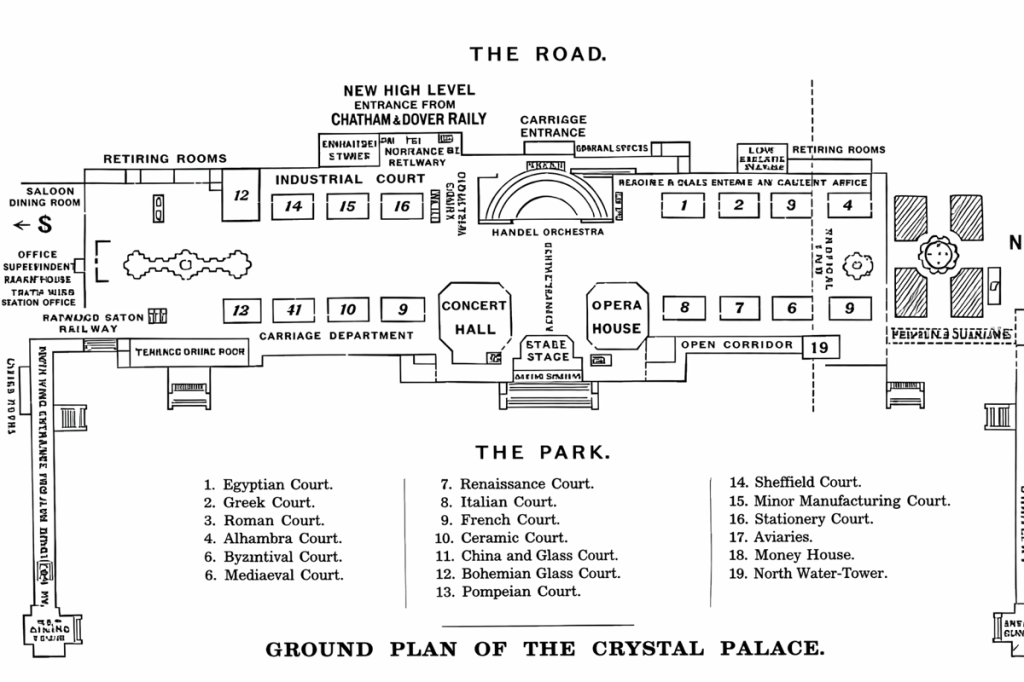

- To raise money and still keep the chalet within the country, it was put on show at the Great Exhibition in Sydenham, London.

- Lord Darnley offered sanctuary for the chalet on his estate when it was ‘retrieved’ from the Crystal Palace Company.

- When money became tight in the 1920s, Lord Darnley made extensive efforts to sell the Chalet. It was marketed in England and America as well as being offered to the Mayor of Rochester.

- Eventually, much later, the Ministry of Works ‘sold’ the Chalet to the Rochester Corporation in the expectation of the public having access. The work required extensive timber preservation work before it could be re-erected.

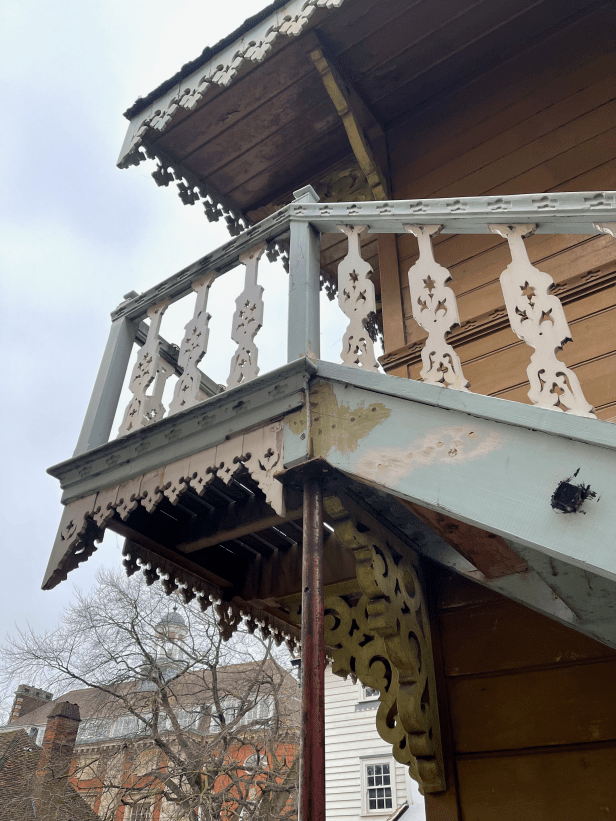

- Sadly, the chalet is on ‘life-support’ again, held upright/square by huge internal beams, and the balcony being held up by a combination of wood filler and acrow props.

This is the Chalet’s story as currently known –

I’m hoping by telling it, it will have a happy ending.

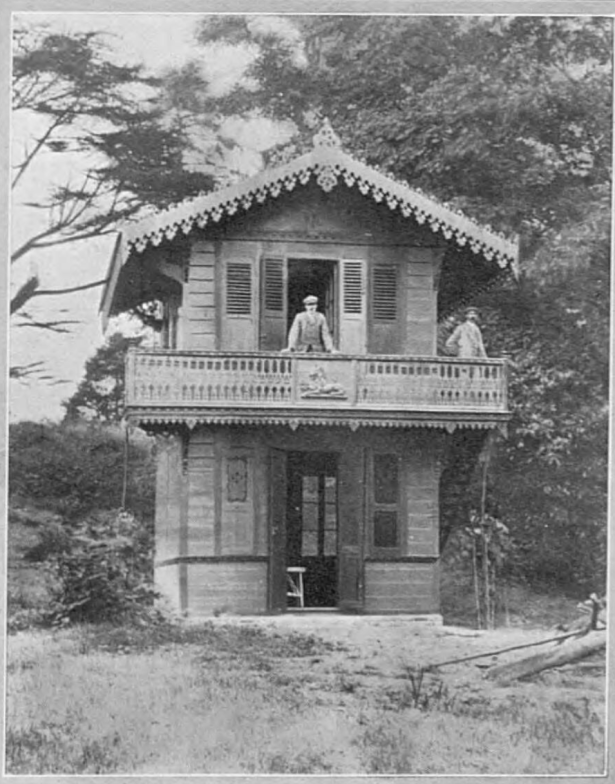

A ‘Compilation Biography’ of Charles Dickens’ Writing/Swiss Chalet

Dickens’ Swiss or writing chalet, which is now located in the grounds of Eastgate House, Rochester, has had quite a journey to get there – Innsbruck, Higham, Sydenham (South London), Cobham (Kent), and finally Rochester. During its ‘journey’, it was saved more than once from being lost to the nation and dereliction – a condition it finds itself in again. It’s screened off because of its dangerous condition; held square by huge internal beams, and the balcony being held up by a combination of wood filler and acrow props.

I am actively advocating for steps to be taken not only to save the Chalet but to return it to being a cultural and educational asset, and to create some commercial use whereby any income could used to prevent it from returning to a deplorable state – again. Lord Darnley, and the various iterations of Rochester Corporations, have all failed to find a respectful way monetarise the chalet and have allowed it to fall into a state of disrepair.

I’m producing this blog in order to place the story of Chalet and a case for its restoration, out there, in the hope that it will help those who could fund or may apply for funding to save the Chalet. It is perhaps time to move the chalet into community ownership?

What is known of the Chalet’s story is spread around various sources. My intention is to pull together what we know of the Chalet into one piece/place, and to reference my sources. This blog now probably represents the most complete record of the Chalet’s ‘life’ that can be found on the internet and perhaps in print – January 2026. However, having made such a claim, many of the sources are newspaper articles and therefore need to be regarded as secondary sources. They can be contradictory, cut and pasted from one or other newspapers – and may even have been made up!

How did the Chalet arrive at Higham, Kent?

The Chalet was a gift to Charles Dickens from his Anglo-French friend Charles Fechter— a successful actor, playwright, and perhaps not so successful theatre manager. One news report stated that the “famous chalet was given to Mr Dickens by English residents in Switzerland, and brought to England by Mr Fechter.[1] Another report suggested something similar— but using distinctly different wording: Dickens prior to his death spent time … “in the chalet presented to him by a few Swiss admirers two years since.”[2] A report of the auction of Dickens’ property stated that “… the pretty Swiss edifice brought over by Mr Fechter and presented to the novelist.”[3] Could this explain why some news reports say it was ‘presented’ rather than ‘gifted’ by Fechter?

It was reported sometime after its arrival that the chalet was transported from Paris to London. From there, it made its way to Rochester by water [4], and presumably by rail to Higham. Dickens had noted when he purchased Gads Hill Place that a “railroad has opened from Rochester to Maidstone, which connects Gads Hill at once with the whole sea coast.”[5]

The Chalet comprised two square rooms (19 sq. ft.), one on top of the other. The upper room was reached by an outside staircase. One description stated that “each room was furnished with seats covered with purple Morocco leather and a commodious table, the walls being plain polished pine.”[6] (Some news reports talk of the ‘upper two rooms’. I suspect this is a typographical error. The statement should perhaps read the ‘upper of two rooms’. There is no evidence that the upper room had been divided into two very small ‘apartments’.)

What do we know of the Chalet’s Background?

In short, not a lot – at present. The Peninsula Times stated in December 2012 that the Chalet was made in Innsbruck but provides no reference to back this up. What we do know for sure is that it arrived at Higham in 1864 as a flat-pack comprised of 94 pieces packed into 58 cases. It was reported in The Christian Science Monitor that the Chalet was accompanied by a French workman who was to help with the construction. He was, however, unable to assist, so the services of Mr J Couchman, a master builder and undertaker, of Strood, were obtained. He had previously undertaken alteration work on Gads Hill Place [7], when Dickens purchased it, as well as having built a kennel for Dickens’ dog.

The Frenchman apparently stayed the night and went away the next day. Based on other reports, the French workman may have been a carpenter, M. Godin[8], from the Lyceum theatre.[9]

The obstacle to constructing the puzzle of the Chalet was the instructions being in French. Dickens’ son, Henry, who had some French[10], [11], helped Mr Couchman to identify the names of the various parts. He was thus able to construct the Chalet, in an area known as the Wilderness, situated between two Cedars. (A letter sent to the then Lord Darnley, in 1927, stated the Chalet needed to be placed on a strong brick base.[12]

The Wilderness, also referred to as the Shrubbery, was a piece of land that was on the opposite side of what was, at that time, the main Gravesend to Dover Road. Dickens had acquired this separately from Gads Hill Place for £90.[13] To reach this area, Dickens obtained permission to construct a subway from the lawn in front of the house to the Wilderness under a very busy road. One unreferenced source says it was constructed in 1859 to avoid the traffic and mud;[14] this was five years before the arrival of the Chalet. The work, according to Alan S. Watts, was overseen by Dickens’ brother Alfred.[15] He, though, was a violinist, but it was his brother Frederick who was a trained civil engineer. It’s more probable that a civil engineer would have overseen such a construction.

Clearly Dickens would have wanted to avoid heavy traffic or the need to paddle across a road covered in mud and ‘horse-exhaust’, but once the chalet had become a workspace, I also suspect he would have wanted to avoid his journey to the chalet being interrupted by tourists/fans[16] or people who could have known of Dickens’ generosity.

“No country road, perhaps, in England is so much traversed by tramps and beggars as the high-road between Gravesend and Rochester, especially in the hop season, when London seems to pour out every available kind of pauper—male, female, and child for the hop-picking; although, be it said, amongst this class even, there were some to whom a deaf ear was never turned when they made their necessities known to the owner of “Gad’s or his amiable family.”[17]

The Chalet in-situ

An illustration of the Chalet published in the Illustrated Times in 1870 suggests that the gradients of the Wildnesses necessitated Dickens to occupy the upper storey as his study; this would have afforded him the views that he so appreciated:

The Swiss Chalet was “erected in the shrubbery opposite his residence, and approached by a tunnel underneath the turnpike road. This chalet, embosomed in the foliage of some very fine trees, stands upon an eminence commanding a magnificent view of the mouth of the Thames, and the opposite coast of Essex.”[18]

Various other descriptions of working in the chalet were reported in the press— all probably taken from John Foster’s “The Life of Charles Dickens”, that was published in 1875— and is available free as an ebook.

“my room” he writes, is up among the branches of the trees, and the birds and the butterflies fly in and out, and the green branches shoot in at the open windows and lights and shadows of the clouds come and go with the rest of the company. The scent of the flowers, and indeed everything that is growing for miles, and miles, is most delicious.”

“I have put up five mirrors in the chalet where I write”, he told an American friend (possibly James / Annie Fields [19]), “and they reflect and refract, in all kinds of ways, the leaves that are quivering at the windows, and the great fields of waving corn, and the sail dotted river. My room is up among the branches of the trees, and the birds and the butterflies fly in and out, and the green branches shoot in at the open windows”.[20]

Another reporter recorded Dickens describing working in the Chalet:

“Altogether it is a charming spot, but beautiful and grateful to the eye as are the hues of the masses of foliage in the background, all would fall almost into commonplace without the two grand cedars which flank the exit from the subway on either side. These magnificent trees, with their vast boles and arms, their dark green leafage, their crowded and pensile branchlets. must have been to one of Dickens’s temperament like a perpetual benediction.”[21]

His friend John Foster also wrote that Dickens “made great boast .. not only of his crowds of singing birds all day, but of his nightingales at night.”[22]

The Upper Room of the Chalet . The Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens

The following is claimed to be a picture of Dickens’ desk in the chalet. Doesn’t look the same. Perhaps there were two? No evidence to support this.

Mamie, Dickens’ daughter, said her father made use of the mirrors to ‘perform’ his characters. There were no books in the chalet, and the desk faced the mirrors rather than the window.[23]

On the front of the balcony railings can be seen an ‘unofficial’ coat of arms/family crest. It seems that John Dickens, father of Charles, and probably the basis of Mr Micawber, appropriated the crest of William Dickens—a merchant and first cousin once removed of John. It was of a laying-down lion holding a “cross patonce”. In 1840, Charles Dickens commissioned John Overs, a cabinet maker, to redesign the crest—replacing the cross patonce with a Maltese cross. The history suggests Charles did this to separate himself from his profligate father.[24]

When this crest was added to the Chalet is yet to be discovered – but it is present in photos of the Chalet when located in Cobham Park. It is also shown in a sketch of the Chalet when located in the Shrubbery at Gad Hill Place – however, this sketch was dated 1912.

Disposal of Dickens’ Estate

Dickens died on 9 June 1870, leaving the copyrights to his works worth nearly £80,000 for his family. He had completed the fourth, fifth, and sixth monthly parts of ‘Edwin Drood’ and an outline of the remaining portion of the story in what Dickens termed his ‘waste-book’. Wilkie Collins apparently took this material with the intention of completing the story. [25] However, it was also reported that Dickens’ publisher, Messrs. Chapman and Hall, had stated that they would not permit another writer to complete the work that Dickens had left.[26] Items other than the copyrights, which would have had enduring income potential, were disposed of.

House & Chalet of National Importance

There were many of the view that Gads Hill Place and the Chalet should not be sold. Within two weeks of Dickens’ death, the press was reporting on discussions happening in Rochester about what should happen to Gads Hill Place and the Swiss Chalet— presumably because its disposal was being advanced? Under the headline of “Proposed Memento to Charles Dickens”[27] “It was being suggested that the house should be retained by Mr. Dickens’ family for a term. At the end of this period and with the consent of the family, the place will merge in trustees”.[28]

An auction of Gads Hill Place and its contents commenced on Friday, 12 August 1870. It was reported that the auctioneer was strongly urged to offer the chalet as a separate lot but declined to do so.

National Pride requires No Foreign Buyers!

It was thought that had the Chalet been sold as a separate lot, a large amount of money would have been bid.[29] The auctioneer stated that he had received several applications for the purchase of the Chalet. He mentioned that some Americans had made an offer for the Chalet, and one gentleman, it was said, was determined to purchase the Chalet at any price. The auctioneer went on to state that he “hoped that a feeling of national pride would prevent the house passing into the hands of any foreign agent” – a comment that was met with applause.[30] In the belief that it would be sacrilege[31] to sell the Chalet separate from the house, buyers wanting the Chalet would have been obliged to bid for it and the house; something which would have curtailed some interest.

In the same report, it was stated that though many attended the auction, there were few bidders. It was said that many present were aware that Charles Dickens jr., (Charley), was bidding, and those likely to bid had been informed that the family desired to retain the house. Great satisfaction was apparent among those present when it became known that Mr Dickens had become the proprietor of his late father’s residence.[32] [Charles Dickens jr. purchased the house and garden with the Chalet for £6,000 – much below the guide price.[33], [34]. Another report states Charles Dickens jr., paid £6,600. The auctioneer initially offered the property for £10,000, expecting it to go for £20,000 [35]. Bidding, though, started at £5,000, which went up in increments of £100.[36] (In 1878, Gads Hill Place and contents were auctioned again – but no reference to the Chalet.[37])

Contents of the Chalet

News reports pertaining to the auction of items from the Chalet, after Dickens’ death, offer another dimension of Dickens’ working environment. (These reports also detailed the items sold from the house—which are not covered in this blog.)

[‘Bank of England Inflation Calculator’ estimates that £10 in 1870 could be worth around £1,000 in 2024. S = shilling. There were 20s to the £.]

“In the upper [of?] two rooms Mr. Homan [auctioneer] stated Mr. Dickens spent the last afternoon of his life, and the competition for the tables, stools, and chairs in the room was very keen. A bird’s-eye maple cane chair which Dickens used realised £11; the oak table, 4 feet by 2 feet, on which he wrote, brought for £5 (strong competition [38]); the stools from 14s. to 18s.; and the looking-glasses, 36 inches square, in maple frame, prices varying from 32s. to 36s.

“An empty oak tool box, which was in the lower room, measured 2ft by 14in.[39] This report stated it was £3 6d.”[40] [Should be £3 3s as it seems to be accepted the box sold for 3 guineas].

Provenance adds value

“The tool box was about to be sold for 10s until the auctioneer mentioned the name ‘Charles Dickens’ was engraved on the lid.[41]

“The furniture in the Swiss chalet commanded great attention, and there were many eager bidders, An oak tool chest about 2 feet by 14 inches without tools sold for three guineas ; an oak table said to be the one on which Mr. Dickens last wrote, £5. The bird’s-eye maple bergia arm chair, the one in which he constantly sat when in the chalet attracted many bidders, and after sharp contests between three or four who were anxious to possess it, it was knocked down for £11.[42] “.. the purchaser being understood to be the schoolfellow of Charles Dickens, who is so pleasantly referred to in the ‘Uncommercial Traveller’, as Dr Specks of Dulborough Town.[43]

The Chalet’s Journey – Higham to Sydenham

There are many conflicting views on how the Chalet, albeit for a short time, entered the custody of the Crystal Palace Company at Sydenham. It is unclear what rights the Crystal Palace Company secured over the Chalet – from whom, and from when to when. Some reports state that it was sent ‘on loan’ for one year.[44] Other sources say the Company purchased the Chalet[45],[46] from Charley Dickens for £700.[47] Charley would have been in a position to facilitate these arrangements as the owner of the Chalet and the Crystal Palace Press.[48] He is also known to have frequently had financial problems.

Chalet put on show

The company stated that the Chalet would be exhibited “in its virtual condition, in the transept of the Palace”,[49], “in its entirety”.[50]

The putting of the chalet on show clearly upset the family – perhaps suggesting Charley made arrangements without reference to them?

A news report in 1871 stated that the public (“crowds”) did not have the opportunity to see the Chalet – “some difficulties arose, the chalet was again taken down and conveyed to Cobham Hall; where we understand it is now housed but not erected.”[51] It was apparently stored in a barn.

There are three accounts of the ‘cause’ of the difficulties:

1.) Sir Henry Fielding Dickens, in 1929, stated in a letter to Lord Darnley that this was “such a vulgar use of it that it was most distasteful to my sisters and myself”.[52] He went on to state that the arrangements with the Crystal Palace Company were ended. As Gads Hill had been sold, they had no place for it, so we approached the then Lord Darnley. There was no question of a sale – to Lord Darnley. (This has significance later.)

2.) Christine Skelton, in her book ‘Charles Dickens and Georgina Hogarth’, suggests that Georgina and Mamie became aware that the man to whom the Chalet had been sold planned to use it for a touring exhibition.[53] Distressed by this, as perhaps indicated by the ‘accusation’ that the Chalet would become a ‘peep-show’, Georgina made arrangements to purchase the Chalet back. It was much later reported that the Chalet was back for £250 and given to Lord Darnley.[54]

3). A more recent report stated that family objected to the chalet being screened off and the public being charged to view it— something that they thought was no more than a degrading peep-show.[55] No evidence is offered for this view, but it does seem plausible. Interest in Dickens’ memorabilia had been high in 1871, and the Crystal Palace Company was yet to make a profit.

The latter is quite plausible. There had been a fire at Crystal Palace in 1866. The part damaged in the fire was only partially rebuilt due to a lack of money. A new public attraction— an aquarium— was opened in 1871, but financial problems remained (the Crystal Palace did not make a profit after 1884 [56]). Reports of Dickens’ death and stories about his life and work associated with the Chalet would have still been fresh. The ‘acquisition’ of the Chalet in or around 1871 would therefore have helped attract more visitors? [57]

A letter from Kate Perugini, Dickens’ daughter to Lady Darnley stated that “Charley and family lived in the house for “some year” but then needed to reside in London and as our own old home was to pass into other hands, we presented the little chalet to Lord Darnley in remembrance of the kindness he had shown to my father and his friends in allowing them access to his park and grounds.” [58]. (Again no sale, but the chalet was given as a gift.)

For whatever reasons, the chalet’s sojourn to Crystal Palace would appear to have been quick and short, as it does not appear in the exhibition catalogue of 1871—unusual for such a ‘prize’ exhibit?

It was reported that “after passing of the great novelist, Mr Couchman took down the chalet, and for a short period it was to be seen at Crystal Palace. It was subsequently presented by several members of the Dickens family to Earl Darnley, who had been a good friend and neighbour to the novelist. Lord Darnley afterwards ordered it to be re-erected in his park at Cobham where it remains today.”[59]

My assessment of the ‘story’ is that the chalet was sold by Charley to the Crystal Palace Company. On becoming aware of the distress caused to the wider family, and wanting to avoid adverse publicity, the company decided to sell the chalet back to the family. With nowhere to place it, they approached Lord Darnley.

The Chalet’s Journey – Sydenham to Cobham Park via Barn?

The Chalet’s ‘stay’ in Sydenham, though, must have been very short. In much less than a year of Dickens’ estate being wound up, there were news reports that the Chalet had been reconstructed in the grounds of Cobham Hall.

There are diverse reports as to how Lord Darnley acquired the chalet – it was given [60],[61] it was presented [62], [63], [64], it was purchased.[65] The terms of the ‘acquisition’ became a ‘hot issue’ in the 1920s when the then Lord Darnley wanted to sell the chalet.

Provenance – owned, gift, held in trust?

The following is largely drawn from correspondence to Lord Darnley. The number of communications sent around the same time, on the same issues, suggests the writers were responding to enquiries from Lord Darnley. This could be explained if Lord Darnley was considering the sale of the chalet and needed to be able to prove the chalet was his to sell. Any prospective buyer would have needed to have satisfied themselves of this as part of due diligence enquiries.

Mr C H Scriven, FSL, was the land agent and surveyor who acted for the Earls of Darnley in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He wrote to A A Arnold and Lord Darnley in August 1927 concerning his recollections of the chalet coming to Cobham Hall.[66] He believed the chalet arrived at Cobham Hall on 14 Feb. 1871. It stood in the park opening at Cobham Hall for some years and was moved to the south part of the pleasure ground and was moved again to its present place [in the park] about 1910. He reported, without giving names, that two people stated that Lord Darnley purchased the chalet from Mr Budden, who was as executor of Dickens’ will, for £50. [A A Arnold of Rochester was amongst many roles regarded as an antiquarian. He was thanked for his assistance in “A Week’s Tramp in Dickens Land” by William R Hughes. This suggests his advice was being sought in respect of any chalet-related documents that he may have been aware of? Presumably Lord Darnley had engaged his services.]

Regardless of how Lord Darnley acquired the chalet, it was relocated to the grounds of Cobham Hall—some distance from the hall— a move that does not seem to have been universally welcomed.

The Chalet may have had three different positions in Cobham Park

The Chalet become an ‘Attraction’ – for a few Dickens aficionados

There are letters held in Medway Archives from the Dickens family to Lord and Lady Darnley, requesting permission to take friends and family to see the chalet.

A news report in 1885 criticised a “noble lord” for taking the chalet to his own estate; “He is none the better for it, and Dickens’ memorials are the worse.”[67]

In 1904, Lord Darnley gave the Dickens Fellowship, that was undertaking a tour of places with Dickensian connections, the opportunity to visit the chalet that was said to be situated in the earl’s private gardens.[68]

During 1912, there were a number of events to mark the centenary of Dickens’ birth. In July of that year, the Lord and Lady of Darnley held a reception at Cobham Hall for around 100 members of the Rochester Branch of the Dickens Fellowship. The party included Mr & Mrs Edwin Harris and Mr & Mrs A W Ratcliffe. The party had a tour of the Hall conducted by Lord Darnley and a visit to the Chalet. To mark the occasion, the Fellowship presented a centenary edition of ‘David Copperfield’ to Lady Darnley. The Fellowship also presented to ‘Mr Secretary Radcliffe’ a handsome silver cigar case and a silver tea service to Mrs Radcliffe, as mementoes for services rendered.[69]

In 1916, upwards of 100 teachers from Gravesend, Maidstone, and Gillingham met at the Ship Inn in Cobham. After their meeting, they were taken on a tour of the private grounds of Cobham Hall. On reaching the Swiss Chalet, the teachers sang the National Anthem in acknowledgement of it being the King’s Birthday.[70]

“One of the most remarkable houses of literature” is put-up for sale

Due to heavy death duties and the impoverishment of the land, Lord Darnley (6th Earl) said in 1929 that he was compelled to sell up and place the chalet, that had been given to his grandfather, on the market. There is, though, evidence in correspondence held by Medway Archives that he proposed to sell the chalet as early as 1927.

Under the headline “Dickens Relic May Go To America”, it was reported that the Mayor of Rochester had said “that a great effort is to be made to save the Chalet for the nation”. Lord Darnley similarly wished “that this national shrine” should rest in the heart of “Dickens’s Land”. This, though, would only be achieved “if all lovers of Dickens will combine and offer a sum which will compensate the Earl”. In order to allow time for local money to be raised, the Earl withdrew the Chalet from sale “for patriotic and sentimental reasons”, but he could not afford to accept a too smaller sum.[71]

“… although he [Lord Darnley] has said that Rochester shall have first refusal of it, he does not appear to have stated a price at which he is ready to effect a sale. As Rochester is expected to start bidding, it does not look very hopeful that the city of Rochester will be able to possess itself of one of the most remarkable houses of literature…”[72]

Walter Dexter, editor of the Dickensian, also expressed the fear that the ‘portability’ of the Chalet could make it attractive to an overseas bidder. He felt the Chalet should be secured for the nation and placed in the Castle grounds at Rochester.[73]

The risk of a sale to America was significant. Dickens was well known in America and had a number of friends there. Despite the new owner of Gads Hill Place refusing access, many hero-worshiping Americans continued to visit Gads Hill Place— “eager to see the last home of the eminent novelist.”[74]

An appeal for public donations was made in the Chatham News. It took the form of a letter from Edwin Drood to the people of Cloisterham, as Dickens referred to Rochester in his Mystery of Edwin Drood.[75] (Chatham News 22 Fen 1929). After commenting on aspects of Rochester, ‘Edwin went on to write’:

“you will do yourself a grave injustice my good friends of Cloisterham if you allow the Chalet of beloved memory to find the house in any place in the World. Never mind what it costs you, back up the appeal of the Worshipful Mayor to the utmost of your powers. Don’t let such a tangible memory of that unparalleled genius go elsewhere if you have any respect for your city, your name or yourselves.

I understand someone promised or gave half a crown to the Mayor. That’s a good beginning. Let everyone in Cloisterham or Kent, man, woman, even Tiny Tim’s children, go and do likewise according to ability, and so remove all possibility of reproach. Wishing you all good luck, believe me. Yours sincerely, Edwin Drood, in the Fields Elysian. Feb 1929.” (Elysian is a poetic reference to heaven or paradise.)

“There must be no breaking of it up to make furniture or paper knives”

Prior to offering the Chalet to Rochester, Lord Darnley had instructed agents to seek potential buyers in England and America. The agents included Knight, Frank & Rutley (Dec. 1928), Christie Manson & Woods (Christies) (May 1928), and Sotheby’s (Dec. 1929). In offering the Chalet for sale, Lord Darnley stated that any buyer, prepared to pay the price, must give a guarantee that it will be kept intact in perpetuity – “There must be no breaking of it up to make furniture or paper knives”.[76]

The following two images were taken by the Sunday Pictorial in the 1920’s. They may well have been used as part of the prospectus sent to agents and potential buyers. They would have been taken of the chalet in its final location in Cobham Park. They maybe of assistance to those who (hopefully) will undertake restoration work.

Lord Darnley was somewhat coy about advising his agents of the price he expected for the chalet. This made it difficult for them to identify potential buyers. Correspondence held in the Mayday Archives indicates that before the end of 1928, he had a price of £25,000 in his mind; a price that he appears not to have declared to Rochester, who had been given first refusal.

All agents advised that this amount was unrealistic. It was the equivalent of about £1.3m in 2025.[77] Knight, Frank & Rutley advised Lord Darnley that this high price was unrealistic because Charles Dickens’ literary connection with the Chalet was limited. It had only been in his ownership for five years. Other than the unfinished Mystery of Edwin Drood, he had not penned any of his other notable works in the Chalet.[78]

In December 1929, Lord Darnley approached Sotherbys for assistance. By this time, he had reduced his expectations to £10,000 for the chalet. He also offered a 5% commission for finding a buyer.[79] Sotherby’s were quite forthright in their response. They undertook to make enquiries in America, but they were not optimistic.

“We must say frankly, however, that the market for relics of literary meaning is by no means strong just now, as compared with autograph letters, manuscripts or fine 1st editions, and we do not ourselves see any reasonable probability that a buyer could be found to pay so high a price as that which you mention.”

In addition to appointing agents, Lord Darnley also sought assistance to find a buyer— particularly in America. Both Britain and America face economic challenges in the 1920s. In Britain it was a period of depression, deflation and steady decline following the end of World War 1. A potential buyer in America, was found in 1931, but owing to his financial circumstances, he was unable to find the money.[80] (In the 1930s, America was experiencing the ‘Great Depression’.)

Due diligence

All those acting for Lord Darnley sought information about his ownership, and proof that Charles Dickens had actually written in the chalet that was being offered for sale. Was it a ‘gift’? Was it being held in trust for the family? Was it purchased from the family by Lord Darnley? Unless undisputed ownership could be provided, any potential buyer would rightly be cautious— particularly with regard to the expected price, and if the potential buyer was an American, they could well be buying the chalet unseen.

The question of entitlement remains open. There are claims made by family that the Chalet was given as a gift for Lord Darnley’s kindness to Charles Dickens and his friends [81], or it was passed to him ‘in trust’ as the family had nowhere to put the Chalet when they retrieved it from the Crystal Palace Company. Other sources say that the then Lord Darnley in 1871 paid £50 [82] or £60 [83] for the Chalet.

Had Lord Darnley found someone prepared to pay his high asking price, I suspect the sale may not have gone through. Any lawyer acting on behalf of the potential buyer should have advised caution. Based on records seen whilst preparing this blog, it is unclear that Lord Darnley could prove ownership of the chalet, and therefore his entitlement to sell it.

As it happens, it all became academic at the time as no buyer was found, and the authorities in Rochester had not raised the amount of money Lord Darnley was seeking for the Chalet. Without a sale, the Chalet remained in the grounds of Cobham Hall; unloved and unwanted, the Chalet continued to deteriorate.

In 1959, Lord Darnley, unable to contribute towards the repair of Cobham Hall ( £25,000 was required [84] – he sold the Hall to the Ministry of Works.[85]

Who would ‘love’ the Chalet the best?

There are conflicting reports as to whether the Ministry of Works sought bids for the Chalet or whether Mr Charles Eade, a well-known Dickensian and owner of Bleak House at Broadstairs, spotted an ‘opportunity’.[86] He stated he would spend £600 (c£12,000 in 2025) on having it relocated, and once done, he would open the Chalet to the public.[87]

Mr Eades’ proposal was countered with one that involved relocating the chalet to the grounds of Eastgate House. Here it would be fitted out with Dickens’ desk and papers, that were held by the museum, and thereby transformed into the study that could be shown to the public.

The Rochester Corporation offered to set the chalet on a concrete base behind the museum, Eastgate House— a building with associations with Charles Dickens’ work.[88]

Strood Council made a counter-proposal to the chalet being moved to Rochester under the headline “The struggle for Dickens’ chalet – Strood enters the field”. Strood Council stated it felt that the parishioners of Higham and Cobham should be consulted as there was a case for the chalet to be sited in Cobham Village or to be returned to Gads Hill Place.

It appears that the Ministry of Works may have looked at these possibilities, as it was pointed out that no suitable location had been found at Cobham, and that Gads Hill Place was now privately owned [89] – which presumably would have prevented public access. Strood Council therefore decided to recommend to the Cobham Parish Council that the chalet should be left where it is and that it should take on responsibility for its maintenance.[90]

Despite Strood Rural District Council’s protest and appeal not to move the Chalet, it was reported in April 1960 that the Ministry of Works had decided that Rochester Council should receive the Chalet and re-erect it in the grounds of Eastgate Museum – “… so it could be preserved and kept available for visits by the public.”[91]

The Chalet’s Journey – Cobham to Rochester

Eastgate House – before the Chalet’s arrival

In April 1961, work commenced on dismantling and treating the timbers of the chalet in advance of its being moved to Eastgate House [92]:

“This week, among the spring flowers which now carpet Cobham Park, where the chalet has stood for many years, a team of tradesmen, carpenters and joiners are dismantling the building, piece by piece.

These experts are members of Woodworm and Dry Rot Control Ltd., who have taken on the difficult task of dismantling the building, restoring it to its original character, and moving it to Rochester.

All the sections are being housed in a large marquee in front of ancient Cobham Hall where other experts are examining and treating the timber.

Quite a considerable amount of the wood is affected by woodworm and damp rot and this will receive special treatment from the experts, while that which is irreparable will be replaced by matching pieces.

It is no easy task, requiring a lot of delicacy and patience. One of the major difficulties, according to Mr. V. S. Hancock, the timber infestation surveyor, was choosing a method of taking the building down.

Another problem was conveying the pieces from the woodland site to the marquee without damaging the surrounding property.”

Bearing in mind the number of times the chalet was relocated, and the extensive renovation before moving to Rochester, how much of the current construction matches that which arrived at Higham?

Public helped fund the relocation?

“… it will not be long before Dickensians in the Medway Towns, many of whom are helping towards the cost of the project, estimated to be almost £1,500, will have an opportunity of seeing the Chalet in all its splendour at Rochester.”

“Just one more move now and the Chalet will finally rest in the very heart of the area where Charles Dickens created some of his most famous and well-loved characters.”[93] (This was incorrect. Only part of the Mystery of Edwin Drood was drafted in the chalet.)

Other reports state that the cost was met by the Council and the Dickens Fellowship as well as with a £1,000 charitable grant.[94]

Chalet Opens to the Public

In November 1961 the opening ceremony was performed by the “Countess of Huntington better known as Margaret Lane, author, critic and president of the Dickens Fellowship. She claimed that the chalet was sold to Lord Darnley by Charles Dickens daughters and sister-in-law. Several made a bid for the chalet but Countess Huntington said she persuaded the Ministry of Works that the Dickens Fellowship had most right to it. “It was a question of raising the money for the transportation, erection and maintenance of the chalet, and it was suggested to me that I might ask the Wolfson Foundation for financial help” – £1000 was awarded.”

It would appear that Wolfson Foundation may have needed some persuasion as Lord Burkett was credited with persuading the Isaac Wolfson Foundation to make a donation.[95] A later report stated that the Chalet officially opened on 22 Sept, 1961 [96]; perhaps there is a distinction between being ‘opened’ and being ‘officially opened’?

Criticisms were soon being voiced (1965) about the location of the Chalet. One press report observed that although the Chalet was a “Mecca” for tourists from around the world, it was hidden in the grounds of Eastgate House. It was observed that coach-loads of Americans visited the Chalet en route to Canterbury, and had been visited by Russian students and local government officers from New Zealand, as well as Bulgarian dancers. The reporter, though, was pleased that the Council had decided to re-prioritise the painting of the Chalet, although colours had not been decided.[97] [NB: painting – not re-painting, and presumably there was no colour to be matched – could it be that it had not been previously painted? See below.]

In July 1978, the Rochester’s Dickens Fellowship presented two mirrors paid for by Amy Butler of Maidstone Road, vice president of the branch, and with money from a legacy left to the fellowship by a former member. The mirror frames were modelled on the originals by pupils of Springhead School of Northfleet. The presentation was part of the branch’s 75th anniversary celebrations.[98]

Should the Chalet be moved to the Esplanade?

A major controversy blew up over the location of the Chalet in April 1977. “The Tory Council” wished to relocate what was described as a “tourist asset and trump card for attracting visitors to Rochester”. The councillors argued that by relocating the Chalet, it would “seduce tourists away from the centre and spread the profits more widely”. Conservationists argued the move would harm the Chalet and it would, at a cost of £9,000, be a waste of money [99]; the Council backed down in the light of “fierce opposition” [100] When Lord Darnley was contemplating the sale of the Chalet, Sir Henry Fielding Dickens said that he thought consideration was being given to moving the Chalet to the Castle Gardens.[101]

Chalet Closes to the Public

The chalet seems to have closed to the public in the early 1980s. Since then, a number of interventions have been made to reverse some of the deterioration— conservation rather than restoration.

In November 2000, £35,000 was spent on some refurbishment of the Chalet. The work was overseen by Eric Gransden, founder of E. C. Gransden Builders and Contractors of Upchurch. All shutters and doors were removed, and parts stripped back to bare wood and restored; this work exposed details that had been lost under layers of paint. Some rails had new pieces spliced into them. Jane Davis, Conservation Officer of Medway Council, stated there was no record of what the Chalet looked like in Dickens’ time, so existing colours were used again; she speculated though that it may have been bare wood and not painted in Dickens time.[102]

Sadly, less than ten years later, the Chalet was in “dire need” again. It was estimated that £100,000 was needed to “fix the icon”. It was reported that the Rochester & Chatham branch of the Dickens Fellowship was steering a campaign to raise £50,000 from the Heritage Lottery Fund. It was also reported that Fellowships in America and Canada were also undertaking fundraising activities.[103]

For the love of the Chalet

People are ‘invested’ in the Chalet, and I’m sure that there would be local, national, and international support for saving the Chalet.

Over 30, then over 40 years later, people were still prepared to participate in fundraising events to save the Chalet – first in 2012 (£417.14 raised – money passed to the Dickens Fellowship), the second in 2022 (£3,284.60 raised so far, from tours, talks, and book sales – money being held by the City of Rochester Society).

The support I received through people’s participation in my tours gives an indication of how people feel about saving the Chalet.

In 2023, I asked people who read my Facebook postings for any memories they had of visiting the Chalet. It was clear that a visit to the Chalet had a great impact on the visitors – particularly schoolchildren – as recalled by their adult selves. It is clear the Chalet stimulated young minds and created memories that stayed with them.

Here are a few of the comments I received concerning a visit – there were dozens – all positive about their visit:

- As children we visited the Dickens festival – all dressed up in Victorian clothes. We played around the chalet and fed the fishes. (WAM)

- I would love to see it restored. I visited when in primary school and really loved it. It’s our heritage and that’s important. (LAR)

- I used to work at the Guildhall museum. There hasn’t been access to the chalet interior since the 80’s. When I went inside it was 1989 it was being used for storage, very damp, rotten and filthy inside full of mouldy furniture. (CG)

- I visited the chalet 1974ish. I was doing a Charles Dickens project at the time. “My Dad asked the museum staff if we could look inside”. They unlocked – “all I can remember is upstairs at the front there was a black desk and chair. (AJ)

- Visited about 50 years ago on a school trip to the museum. My concrete memories are of beeswax and the scent of wood. (KA)

- I belonged to the Museum Club and most Saturdays I was able to sit at his desk, looking into the mirrors which were on the wall each side of the desk so that when you looked in you could see yourself going back loads of times. “For me it was a magical place and always felt very lucky.” (BW)

And how long has the Chalet been neglected?

- I had a month’s work experience at The Charles Dickens Centre in 1989. We could only look around the bottom as apparently it was too fragile to go inside. (JF)

Where to now?

“One of the most remarkable houses of literature” or a ‘Banquet for Mini-beasts’?

What is perhaps overlooked is that a prefabricated structure made of softwood is not designed for longevity and frequent dismantling. It’s therefore amazing that the chalet is still with us after 160 years and a number of moves— perhaps as many as seven. However, it has survived—despite many of its custodians failing to invest in it, or maximising its cultural, educational, and, perhaps most significantly, its fiscal potential.

Pupils from local schools still study Charles Dickens, and some schools arrange trips to Rochester to further their learning objectives. Dickens has long been part of the National Curriculum, and seeing places associated with his writing has to add to the educational experience. In 1996, Year 8 pupils from Linton Village College visited Rochester to explore its Dickensian connections. They greatly enjoyed the display in Eastgate Museum— now gone— and were only able to view the outside of the Chalet.[104]

With skilful and not overly complex management, the Chalet could have been— and could still be— a cash generator for Medway. Although it will require a significant injection of cash now to rectify years of neglect, I can envisage it generating an income that would, at the very least, be sufficient to cover its future maintenance costs.

The Council clearly lacks the finance to restore the Chalet— but inspiration and creative thinking should not be limited by a lack of cash— “when the going gets tough, the tough get going”!

The Chalet has had a number of owners— Dickens, the Crystal Palace Company, Lord Darnley, Rochester & Chatham Dickens Fellowship, and the local authority. What’s to say it couldn’t have another?

The chalet is not, and never will be, robust enough to cope with heavy footfall. I offer in two blogs how the restored chalet could become a seed crystal to inspire new writers and storytellers, and to celebrate writers with a Rochester connection.

LINKS Inspiring future writers

The restored chalet will need more than administration. It will need to be managed and developed by those with a flair, imagination, and creativity. Without this, the chalet will be no more than a wooden building in the grounds of Eastgate House.

As young people tend to say, “it is what it is,” but it needn’t stay that way!

Geoff Ettridge aka Geoff Rambler

January 2026

Sources

Many of the sources detailed below are newspaper articles and therefore need to be regarded as secondary sources. They can be contradictory, cut & pasted from other newspapers, and may even have been made up!

[1] South London Press – 20 August 1870

[2] Illustrated Midland News – 2 July 1870

[3] Era – 14 August 1870

[4] The Christian Science Monitor – 28 Feb 1929

[5] Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News – 10 January 1880

[6] Lady’s Own Paper, 13 Aug 1870

[7] Dickens at Gad’s Hill, Alan S Watts. 1989

[8] victorianweb.org/authors/dickens/gallery/36.html

[9] e.g. www.rochesterdickensfestival.org.uk/swiss_chalet.htm

[10] Maidstone Telegraph – 10 June 1939

[11] Evening Post – 18 April 1977

[12] Letter from Sir Henry Fielding Dickens to Lord Darnley – 31 Oct 1927. Medway Archives – U565/CO65.

[13] Kent on Line – 12 April 2015

[14] Rochester Dickens Festival Website – http://www.rochesterdickensfestival.org.uk/swiss_chalet.htm

[15] Dickens at Gad’s Hill – Alan S Watts, 1989

[16] Demands of fans mentioned in “Charles Dickens and Georgina Hogarth”, Christine Skelton, p42

[17] Charles Dickens as I knew him. George Dolby. 1885. (1912 reprint available free on the internet.)

[18] Norfolk News, 25 June 1870

[19] The Sphere, 16 March 1929. Michael Slater’ biography of Charles Dickens

[20] Leeds Mercury, 16 Aug 1902

[21] County Advertiser & Herald for Staffordshire and Worcestershire, 4 June 1904

[22] The Life of Charles Dickens, Charles Foster. 1875

[23] Emily Bell in the blog of the Huntington Museum – huntington.org/verso/2019/10/right-way-remember-charles-dickens

[24] http://www.martyndowner.com/sale-highlights/charles-dickens-silver-meat-dish

[25] Chatham News, 25 June 1870.

[26] Hampshire Advertiser, 25 June 1870.

[27] Illustrated Midland News – 2 July 1870

[28] Hampshire Advertiser, 25 June 1870.

[29] Shipping and Mercantile Gazette – 6 August 1870

[30] Birmingham Daily Post – 6 August 1870

[31] Daily Telegraph & Courier (London) – 6 August 1870

[32] Shipping and Mercantile Gazette – 6 August 1870

[33] Shields Daily News – 8 August 1870.

[34] Birmingham Daily Post – 11 Aug 1870.

[35] Shields Daily News – 8 August 1870

[36] Hampshire Chronicle – 6 August 1870

[37]Leamington Spa Courier – 9 Nov 1878

[38] London Evening Standard – 11 August 1870

[39] Wakefield Express, 13 August 1870

[40] Wexford Constitution, 13 Aug 1870

[41] South London Press – 20 August 1870

[42] Sun (London) – 11 Aug 1870

[43] South London Press – 20 August 1870

[44] The Sphere, 23 Jan 1960

[45] Manchester Times – 11 March 1871

[46] Hackney and Kingsland Gazette – 4 March 1871

[47] Waterford Chronicle – 7 March 1871

[48] As indicated by “Crystal Palace – a guide to the Palace & Park”. Printed by Charles Dickens and Evans, Crystal Palace Press. Particularly p19

[49] Kenilworth Advertiser, 9 March 1871

[50] Oxford Journal, 18 February 1871

[51] Chatham News – 3 June 1871.

[52] Sir Henry Fielding Dickens to Lord Darnley, 2 Feb 1929. Medway Archives.

[53]‘Charles Dickens and Georgina Hogarth’ – Christine Skelton. 2023

[54] Chatham News, 29 Sept. 1961

[55] Chatham News. 13 May 1977

[56] http://www.thingstodoinlondon.com/footprints/wkcrypaladd.htm

[57] http://www.crystalpalaceparktrust.org/topics/the-parks-history

[58] Letter to Lade Darnley, 10 Dec. 1910. Medway Archives V565/F404

[59] The Christian Science Monitor – 28 Feb1929

[60] The Sphere – 16 March 1929

[61] Nottingham Guardian – 2 November 1959

[62] The Sphere – 16 March 1929

[63] Middlesex Chronicle – 9 July 1904

[64] Gravesend & Northfleet Standard – 22 August 1913

[65] Friends of Cobham Hall Newsletter – December 2021.

[66] Letter from C H Scriven FSI, Burgages, Fordingbridge, Hants. 10/8/1927. Medway Archives

[67] Dewsbury Chronicle – 27 June 1885

[68] Kentish Mercury – 24 June 1904

[69] Gravesend & Northfleet Standard, 5 July 1912.

[70] Maidstone Telegraph, 10 June 1916

[71] London Daily Chronicle, 4 February 1929

[72] The Sphere – 16 March 1929

[73] The Sphere – 16 March 1929

[74] Carlow Nationalist – 22 July 1899

[75] Chatham News – 22 Feb 1929

[76] The Christian Science Monitor – 28 Feb.1929

[77]http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator

[78] Letter to Lord Darnley from Knight, Frank & Rutley – 16 June 1928. Medway Archives.

[79] Letter from Darnley to Southerly’s. 20 Dec 1929, Medway Archives

[80] Letter to Lord Darnley from Sir Walter. 19 Nov. 1931. Medway Archives

[81] Letter from Kate Periguine to Lady Darnley, 10 DEc. 1910. Medway Archives

[82] Letter from Mr C H Scriven to Lord Darnley – 10 Aug 1927

[83] Undated/unsigned letter held at Medway Archives

[84] Kent Messenger, 4 Oct 1957

[85] The Sphere – 21 November 1959

[86] Kent Messenger 13 Nov 1959

[87] Nottingham Guardian – 2 November 1959

[88] The Sphere, 23 January 1960

[89] Kent Messenger, 13 November 1959.

[90] Maidstone Telegraph – 13 November 1959

[91] Kentish Express – 8 April 1960

[92] Tonbridge Free Press – 14 April 1961

[93] Tonbridge Free Press, 14 April 1961

[94] Chatham News – 13 May 1977

[95] Chatham News – 29 Sept. 1961

[96] Chatham News – May 1977

[97] Chatham News – 6 Aug. 1965

[98] Chatham News – 21 July 1978

[99] Evening Post – 18 April 1977

[100] Chatham News – 13 May 1977

[101] Letter to Lord Darnley from Sir Henry Fielding Dickens. 2 Feb.1929. Medway Archives

[102] Medway News – 10 Nov. 2000

[103] Medway News – 1 April 2010

[104] Haverhill Echo – 13 June 1996

Comments are closed.