An account of a black princess ‘rescued’ by a ship that departed Chatham in 1847 to disrupt the slave trade, and who spent six years of her adolescence at Gillingham, Kent.

There is much to be found about Sarah’s life in England – much though unevidenced and sometimes contradictory. I have also found errors in print. I’ve therefore tried as far as I can to cross-check and reference all my sources.

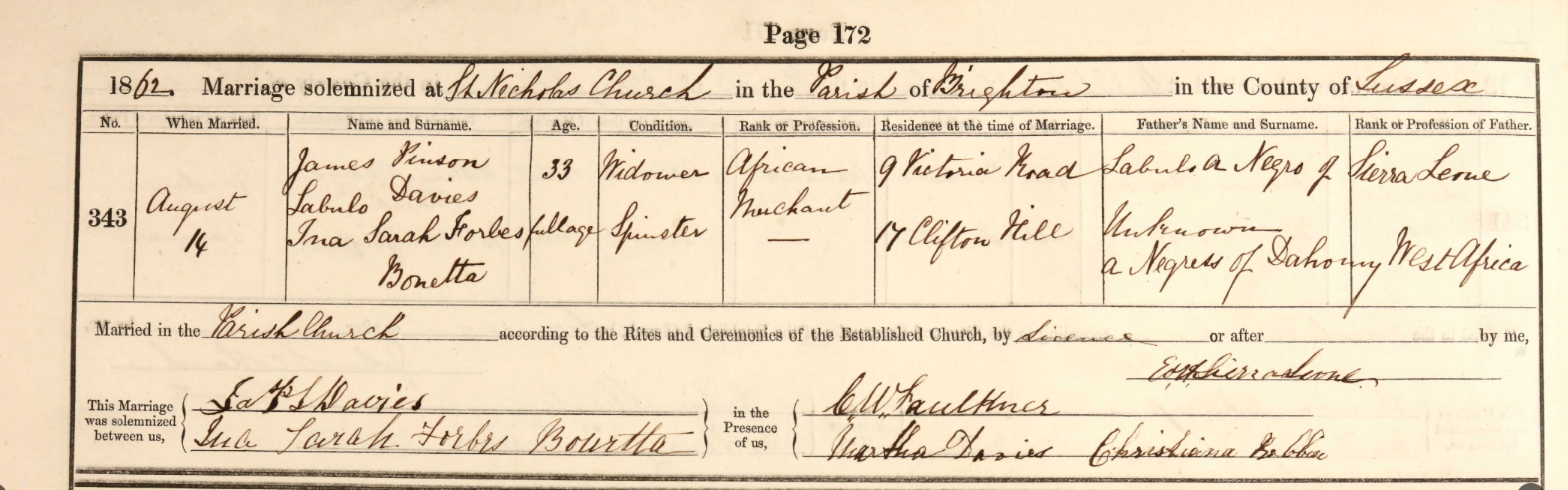

In print and on the internet Sarah Forbes Bonetta has had various names assigned to her. I have settled on and will use, another – Ina Sarah Forbes Bonetta. This is the name and spelling that she used and signed with when registering her marriage in 1862. Most significantly, she used (A) Ina, from part of her ancestral name, as her first name; the other names were given to her when she was Christianised on the voyage to England from Africa.. (The Yoruba tradition, her clan, gave this name to a female child born with the umbilical cord around their neck. (Samuel Johnson, History of the Yoruba, published 1921.)

Leading up to Ina Sarah’s arrival in England

In 1807 Parliament passed an act prohibiting the slave trade in the British Empire. Britain, as a strong naval nation, then took it upon itself to disrupt the trading in people through a combination of soft and gunboat diplomacy, which included the destruction of ports and villages involved in selling people to slave traders. The Royal Navy established the West African Squadron to patrol the coast of West Africa, blocking ports from which slaves were transported and capturing ships used to transport slaves.

Disrupting the Slave Trade

On January 3, 18471, HMS Bonetta departed from Chatham. This 3-gun brigantine (two masted ship) set sail to join the West African Squadron. It was under the command of the respected Lieutenant Frederick Edwyn Forbes – later to become Commander Forbes.

Treaties were agreed upon between the British, Spanish, Portuguese, and Dutch Governments. These treaties gave Royal Naval Officers the right to search ships thought to be carrying slaves. If slaves were found they were permitted to cease the ship. From 1820 the Governments agreed that all slavers could be “seized and condemned if there were “clear and reliable proof that slaves had been on board …” 2

Lieutenant Forbes was successful in capturing a number of ships used to transport slaves. It was reported The Bonetta captured six empty slavers and one full one, with about 400 people to be sold as slaves, on board.3. The captured ships included the Brazilian slave brig Dois Amigos seized on 15 Mar. 1848 , a Brazilian slave schooner, Pharfao captured on 31 May 1848,4 and the slave schooner Louisa, that was captured on 4 Sept. 1848.5 The crew of The Bonetta later received a share of the bounty for the captured ships. (Notices of claims made on the capture of ships, appear to have required them to be registered, and notices placed in the press. On returning to England the ‘prize money’ was distributed amongst the crew after the Crown had taken a large slice; the more senior getting a larger proportion than the more junior. Commander Forbe’s share of the prize of the captured ships was £42 12s 91/2d6 – approx. £4,700 in 2023.

‘Soft Diplomancy‘

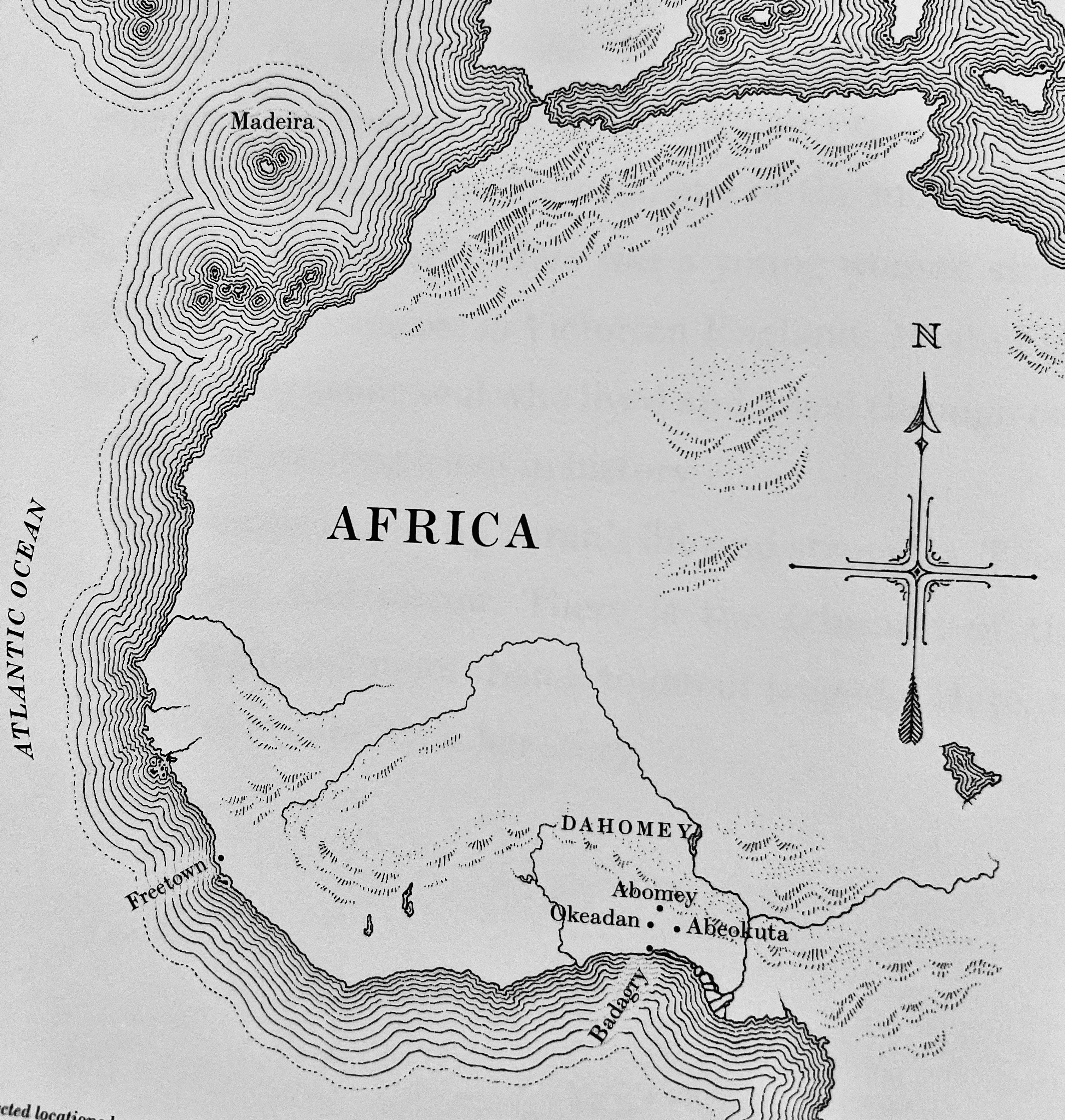

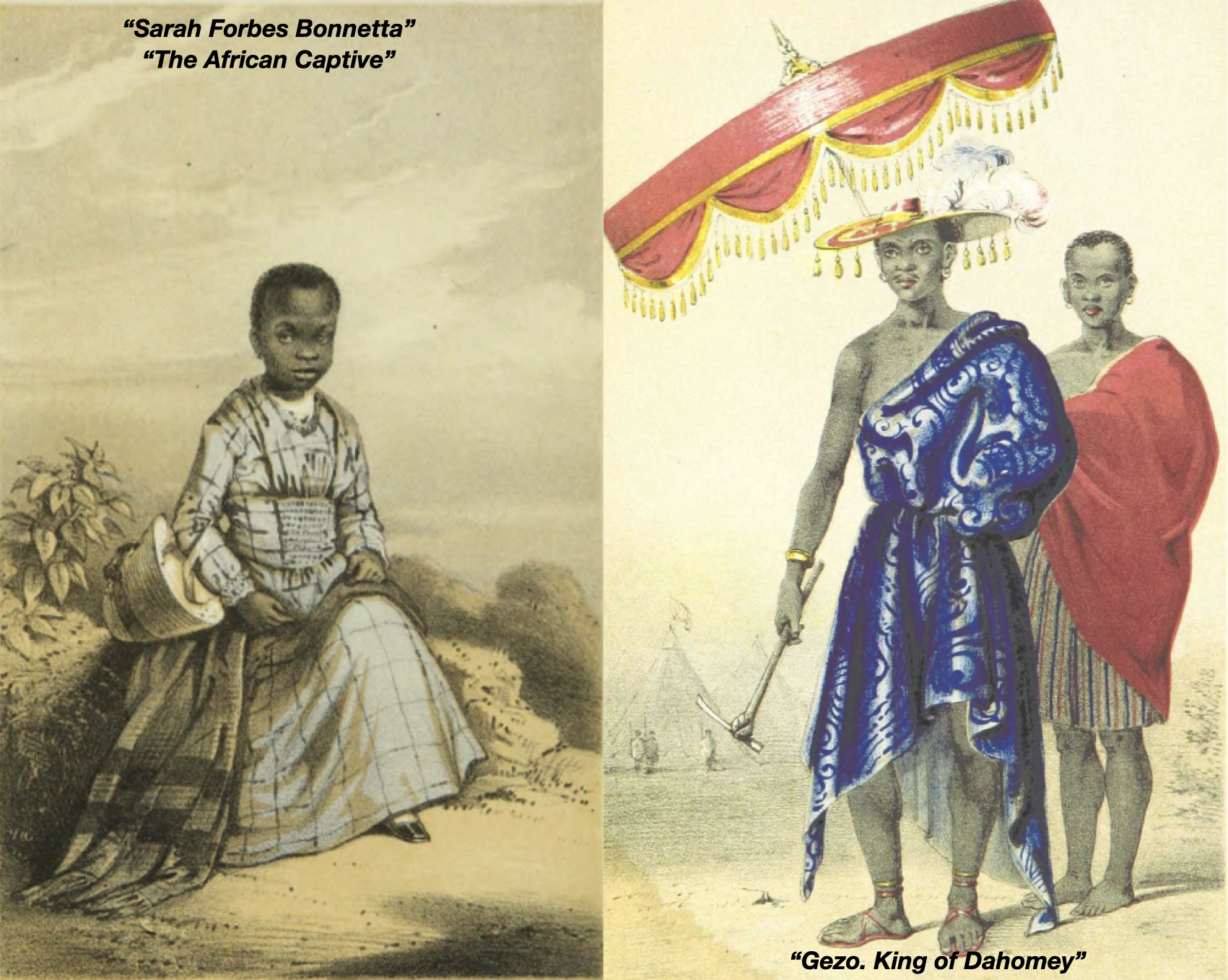

In addition to disrupting the transportation of slaves, the mission aimed to stop the supply of slaves at source. Part of Forbes’ mission therefore included trying to negotiate a treaty with King Gezo (or Ghezo) of Dahomey (present-day Benin). King Gezo was a prominent slave trader with slavery providing the main source of income for his community. The mission hoped to persuade the king to trade in commodities rather than people.

Gifts from a Black King to a White Queen

It was customary on diplomatic missions to exchange gifts. Amongst the ‘gifts’ the King offered was a girl aged about 8 years. Whether Forbes asked for the girl or whether she was offered by the King, amongst other gifts, is unclear.

Forbes in his journal suggests he was reticent to accept a ‘gift’ of a child. After all, it was against the principal purpose of his mission. His goal was the ending of the trading of people. Forbes accepted the girl on behalf of Queen Victoria. He believed the alternative would have been dire for her. He was aware that she may well have been offered as a sacrifice at the funeral of a high-ranking tribes’-person,7 or, as a prisoner, she faced a life of misery and abuse. It was also reported that Forbes saved five others from ‘ancestral sacrifice.’ Three were subjects of the British Realm. He ‘purchased’ the other two for 100 francs each. (A midshipman on HMS Bonetta at the time wrote to the press in 1889, to clarify a press report. He stated that Forbes was sent to Abomey, the capital of Dahomey, on a special mission to the King. This occurred during the annual “Customs.” At this time, prisoners taken in war or slaves are despatched in great numbers. They appease the gods and serve the deceased relatives of the King. The informant stated that the girl was presented to Forbes.9)

On arriving back at Chatham or possibly Gravesend10, England, the press reported extensively on the child that Forbes had returned with. They reported that she had “had the good fortune” of being adopted by Forbes.11

Ina Sarah’s Story

It is perhaps worthy of note that I’ve found little in the public domain based on Ina Sarah’s account of her early life experiences. The following is therefore drawn from news reports and the accounts of Cmd. Frederick Forbes RN, who described her as an African princess by the name of Omoba Aina or Ina 12. Cmd. Forbes wrote in his journal: “Of her own history she only has a confused idea. Her parents were decapitated; her brother and sisters she knows not what their fate might have been”.13

Ina had been taken from the Egbado (known today as Yewa) clan of the Yoruba people when, in 1848, Gezo’s army attacked her village Oke-Odan, during what has been referred to as the Okeadon War.14 Her parents were killed during the raid,15 others of her clan would have been killed or taken as slaves. Ina was held captive as a high-value state prisoner.

On accepting Ina, Forbes brought her to England on the ship the “Sally Bonetta”16 (This is the only reference to the ship being called the Sally Bonetta – and probably wrong. Internet searches have found no ships of this name. The ship was almost certainly, The Bonetta. )

On the voyage back to England Ina was christened Sarah Forbes Bonetta – after the name of the ship and Frederick Forbes who felt some responsibility for her.

During the voyage Ina proved herself to be smart and endearing. Although being given the forename of Sarah, the crew referred to her as Sally – a name that seems to have stuck with Queen Victoria who referred to Ina as Sally in her journal.17 (Sarah at this time was a common name. The diminutive of Sarah is Sally. I suspect it is coincidental that the meaning of Sally is ‘princess’.) [It is probable that among the crew there were black sailors. Through the 19th century, numbers of black seamen on British ships increased. They came from the Caribbean and West Africa, but also East Africa and the Americas. They were deployed on ships that formed part of the West African Squadron ships. maritimearchaeologytrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/BME_booklet_v2.pdf.]

In late September 1850, The Bonetta was paid off at Chatham.18 Reports of the event made reference to Cmd. Forbes bringing back an African princess. She was unnamed in the report but described as a child aged between 7 & 8 “who sung very prettily for a child of her years”. The Queen was notified of the child’s landing and directed Forbes to bring her to London, where she would be pleased to accept the child.19 (There can be no certainty about the child’s actual age – hence inconsistencies concerning Ina’s age at specific events.)

As instructed it was reported that Forbes presented Ina to Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle. (Another contemporaneous news report expected Ina to be taken to Osbourne House to meet the Queen.20)

I suspect that this would not have been Cmd. Forbes preferred course as he seems to have formed a bond with the child. He had given her his name, but as he had received King Gezo’s ‘gifts’ in the Queen’s name. Ina would therefore have been considered as the ‘property’ of the Crown.21 The Queen found Ina “sharp and intelligent” and arranged for her photo to be taken. She paid for Ina’s education too, according to a later press report, to educate her away from .. “the mysterious ways of their ancestors!” 22; the exclamation mark appeared in the press report. Queen Victoria also sent Ina many gifts.

For a year after her arrival in England Ina appears to have stayed with Cmd. Forbes’ family. At Winkfield Place, Berkshire. 23(Not at Gillingham as stated in John Van Der Kiste’s book.24.) She clearly became a respected member of the family. (The 1851 census, carried out on 30 March, listed Ina as being 9 years old and a visitor in the household of John Forbes, father of Frederick Forbes, in Berkshire. This census does not list a Mary Forbes, Frederick’s wife. The census also shows Frederick to be aged 22 where some text state he was 30,25 which is probably correct as he appears to have been baptised in 1819.)

Ina was described as “a perfect genius”. She spoke English well, and showed great talent for music. … “She is far in advance of any white child of her age, in aptness of learning, and strength of mind and affection.”26 This close relationship continued well into Ina’s adult life with the Forbes family members attending and having a significant role in her wedding.

Returned to Africa – for Health Reasons

In 1851 Ina was returned to Africa – Freetown, Sierra Leone. It was believed that the persistent cough she had developed was due to the British climate not suiting her. She was enrolled under the name of Sally into a school for girls – Annie Walsh Memorial School . This school was run by the Church Missionary Society in Freetown. The intention seems that Ina was being prepared to become a missionary.27 Her ‘fees’ were paid by the Queen.28

Queen Victoria continued to show interest in Ina’s health and wellbeing. In 1855, on learning that Ina was unhappy missing Mary Forbes?, the Queen ordered that she should be brought back to England.

By the time of Ina returning Frederick Forbes had died, and his wife was bring up their four children.29 This may explain why the Queen decided to place 12 year old Ina with the Rev. & Mrs Schön, who lived at Palm Cottage, Canterbury Road, Gillingham, Kent, to continue her education. There was apparently once a plaque placed on the building in 2016 recording that “Sarah Forbes Bonetta” had lived there. 31

Mary Forbes appears to have been pleased with the ‘placement’ though she did warn against Ina becoming too conceited. Her concern was that Ina frequently visited theQueen and received gifts from her.32

(The 1851 census shows James and Catherine Schön living at 13 Garden Street, Brompton. [Location now between the public houses of The Cannon and King George V. I wonder if the house attached to the King George V in Garden Street, might have been 13.]

The 1861 census shows the Schön’s living at 109 Canterbury Road – now 189 Canterbury Street, Gillingham, Kent. ME7 5TU. Based on the 1861 census it appears that Rev. & Mrs Schön could have been providing accommodation / education for a number of young people who were not their children.)

Missionary ‘PrePrep’?

It seems possible that the Schön’s may have been running a missionary training facility. In 1857 there was a news report of an African Prince named Frederick Buxton Abegga, being assaulted in the grounds of Rochester Castle. It was recorded that he spoke “tolerable English” and was being educated by the Rev. Schön, Chaplin of Melville Hospital, Brompton, Kent.33

In addition to providing a general education for Ina, there are reports of her attending church functions with Mrs. Schön; one example being a leaving tea-party being held for clergyman leaving his position from St. Paul’’s Church, New Road, Chatham. Ina was not named – she was referred to as “African Princess”.34

James Frederick Schön was a German missionary and a skilled linguist in West African languages. In 1843, he retired to Gillingham, along with his wife Elizabeth Catherine, after 16 years as a Church of England missionary on the Sierra Leone coast.35 (Catherine, as she was known, was the widow of James White a missionary, nee Drake.36). Here he became an active campaigner against the slave trade, and the Chaplin at Melville hospital for sailors, at Brompton, Gillingham, Kent. Rev. Schön was a firm believer that a commercial trading relationship could be struck with Africa in commodities such as cotton. This would he believed replace the income that would be lost through ceasing to sell captives to slave traders.37

The Schön’s later moved to a house and cottage built in “Canterbury Road”. At this time the location looks to be semi-rural. This may have been to accommodate the Schön’s nine children as well as guests from Africa.38

James Schön died in 1889 and is buried in Grange Road. Cemetery, Gillingham.

Invitation to a Royal Wedding

In January 1858 M,rs Schön was commanded to attend Buckingham Palace. This was to receive final instructions in respect of Ina attending the wedding of Victoria, the Princess Royal. To ensure that she was appropriately attired for the wedding, Queen Victoria sent several handsome dresses and all other requisites for Princess Ina to appear, in on the occasion.39 (The wedding between Victoria, Princess Royal, and Frederick William, Prince of Prussia, took place in the Chapel Royal at St James’s Palace on 25 January 1858. This date is significant as some accounts of Ina’s life state that she also married that year.)

Ina – bridesmaid at a ‘not so’ Royal Wedding at Chatham – this appears to be ‘new’ information

In August 1859, at St John’s Church, Chatham, James Schön conducted the marriage of James Pinson Labulo Davies from Sierra Leone, and Matilda Bonifacio Serrano of Lagos. Matilda had for a few years previous been under the care and tuition of the Schöns. “The bride was given away by Mrs Schön and the bridesmaids were Ina recorded as Sarah Forbes Bonetta and the Schön sisters Harriet, Emily and Sarah”. 40

James Davis who had once been enslaved, was now a successful merchant.41

The wedding was attended by 300 guests. The wedding party arrived at St. Johns Church in five carriages at 11am.

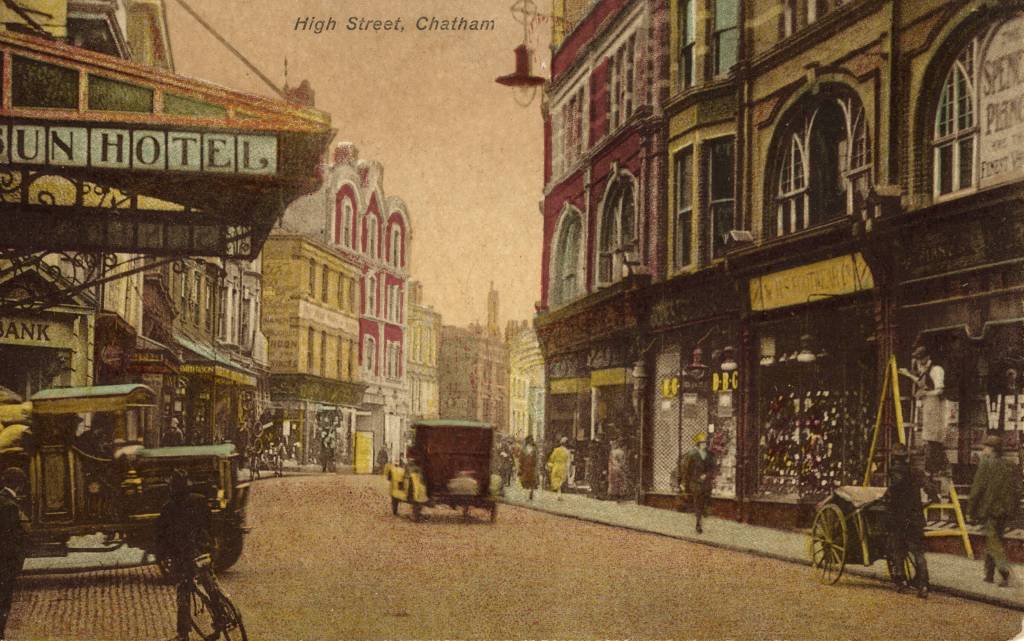

The marriage was conducted by the Rev. Schön and the Rev. J. C. Taylor, native clergyman from Sierra Leone, assisted by the Rev. Conway Joyce, curate of St. John’s Church. After the ceremony the guests left the church in their carriages, and went to the Sun Hotel for the reception. (The Sun Hotel, 85 High Street, Chatham, near Sun Pier, stood on the corner of the High Street and Medway Street. It has since been demolished.)

(Matilda sadly died nine months later (in child birth?) widowing James Davis who subsequently married Ina who had attended his wedding as a bridesmaid – more to follow.)

Enforced Move to Brighton – to force a marriage?

The widowed James Davis expressed an interest in marring Ina shortly after being widowed.42 The Queen having had enquiries made, decided that this was a good match. Ina though was reluctant. Perhaps to make life a little less comfortable / pressure her into marriage, the Queen commanded that Ina leave the Schön household. It was arranged for her to become the companion of Sophia L Welsh (62) – who lived in a household with another elderly lady, Barbara Simon (73). They lived at 17 Clifton Hill, Brighton;43. They were to be responsible for overseeing Ina’s introduction into ‘British Society’.44 This may well have happened between 1861, when Ina was 18, and her marriage at Brighton in 1862. However, news reports suggests that Ina had been residing in Brighton for some years45 – which appears incorrect (This enforced ‘move’ would have been most distressing for Ina. The Schön’s had provided her with the most secure home she had experienced. She had lost her family and community at a very young age, and in tragic circumstances; she had been uprooted from her home country, moved from the Forbes and sent to Sierra Leone, and then returned to the Schön’s, then compelled to move to Brighton.)

(There are accounts of Ina qualifying as a teacher before moving to Brighton. No reference is given and two photos on the net of a black woman claiming to be of Ina holding presumably a graduation scroll, look totally different, and neither like Ina).

Having been ‘introduced into Society’ – and faced with the prospect of continuing to live in a household of elderly women – it appears that Ina was ‘pressed’ into marrying the widowed James Pinson Labulo Davies. He was described as a “merchant and philanthropist” but Ina felt their personalities were incompatible. (I suspect Ina could have been upset by the pressure to marry someone not of her choosing – and to a much older man at that. I also wonder how she would have felt about being made to marry a man whose wedding she had attended as a bridesmaid, two years previous at Chatham?)

Ina wrote to Mrs Schön:

“Others would say ‘He is a good man and though you don’t care about him now, you will soon learn to love him.’ That, I believe, I never could do. I know that the generality of people would say he is rich & you’re marrying him would at once make you independent, and I say ‘Am I to barter my peace of mind for money?’ No – never!” 46.

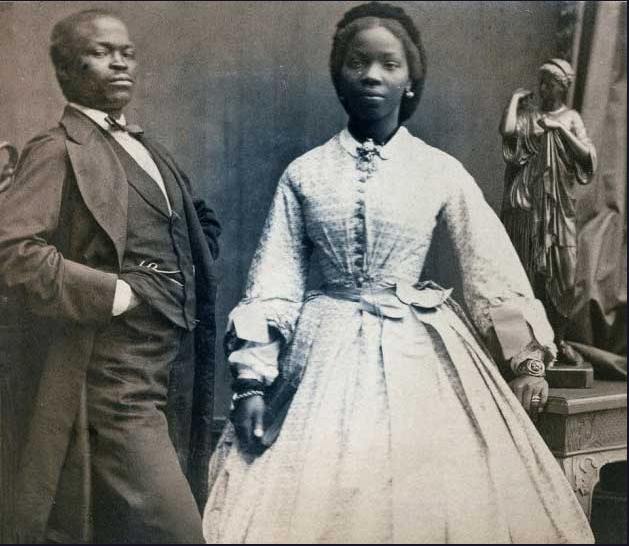

The Queen though thought the marriage would be good for her protégé and the marriage went ahead in August 1862 at St Nicholas’ Church on Dyke Road, Brighton.

At the time of her marriage Ina was recorded on her marriage certificate as living at 17 Clifton Hill, Brighton.

Marriage at Brighton

The reports of Ina’s marriage suggests that she had adopted what is thought to have been her African name: Miss Ina Sarah Forbes Bonetta.47

Although outside of the geographic area that I write about, the report of Ina’s marriage provides some insight into how the Church and the press regarded people of colour. Marriages of people here in Medway and at Brighton were exotic and attracted considerable public interest. However, rather than celebrating differences, some parts of the press highlighted the ‘fact’ that people of colour could be civilised if exposed to good society – presumably compliance with the British way and the Church? In the press, Ina’s marriage was held up as an exemplar of “civilisation caused by the influence of of Christianity upon the negro; and the ceremony will also tell our brethren on the other side of the Atlantic that British ladies and gentlemen consider it a pleasure and privilege to do honour to those of the African rave who have provided themselves capable of appreciating the advantages of a liberal education.”48

A comprehensive description of the wedding was published in the Brighton Gazette on 14 & 21 August 1862, which was clearly a societal affair. The wedding was also reported in New Orleans press under the headline “Mariage d’lune ex-eslave en angleterra” – “marriage of an ex-slave in England”.49

Before providing details of the wedding the press made ethnological observations that Ina was exceptional. The following bullets were extracted from the Brighton Gazette:50

- (Ina) is far in advance of any white child of her age, in aptness of learning, and strength of mind and affection

- … “excellent specimen of the negro race”

- … “it being generally and erroneously supposed that after certain age the intellect becomes impaired, and the pursuit of knowledge impossible —that though the negro child may be clever, the adult will be dull and stupid.”

- (Ina’s) “head is considered so excellent a phrenological specimen, and illustrating such high intellect”

By stressing how ‘exceptional’ Ina was suggests others were regarded as less-so. Although slavery had been abolished embedded prejudices, such as these, would have curtailed opportunities. Reporting though of the marriage was far more enthusiastic – but the opportunity was not missed to highlight the civilising effect of Christianity.

“The African Wedding at Brighton”51

The wedding excited great curiosity – “countless hundreds [on] the streets, along the line of route which the wedding party took. Not withstanding the rainy morning, it did not damp the ardour the people, and the fair sex especially seemed most desirous of satisfying their curiosity, for numbers assembled in the neighbourhood of the Church long before the hour appointed for the marriage – in fact every available space where a sight of the bride and bridegroom could be obtained was thronged.

All the pathways leading to the Church doors were blocked up by ten o’clock in the morning. Curiosity was heightened from the fact that there would be something like 20 persons of colour attending the wedding, and that the marriage ceremony was to be performed by the Bishop of Sierra Leone, assisted by a minister of colour.

In order to manage the number of people wanting to attend the wedding, tickets were issued in order that the wedding party could get into the church.

“… some carriages drove up to the northern entrance, containing the first portion of the coloured marriage party. They included the four bridesmaids of colour, … and their apparel was white, forming singular contrast with their dark faces, and more especially when they stood intermingled with the English bridesmaids. The whole party continued to arrive by degrees, the English bridesmaids following the African ladies, and among the English bridesmaids were six young ladies, varying from six to twelve years age.

Several gentlemen of colour, to the number of eight or ten, including the bridegroom, entered the Church next, and it was quite eleven o’clock before the carriages had done setting down, and then the bride was wanting, in the meantime the south door of the Church was opened to the public.

The rush was enormous, and the pressure so great that many of the ladies screamed. We never remember seeing such a scene, especially in a Church; the crowd rushed towards the altar, of course, to get a sight of the party, whilst others climbed upon the seats or in the windows to elevate themselves and got a view of the ceremony. We should observe that a large crowd had assembled at the northern gates, and, as the wedding party alighted from their carriages, they were loudly cheered by the populace, and the exclamations and remarks of the people excited no small degree of amusement, especially the sight of the ladies of colour.

Ina was given away by Capt. John Forbes – the father of Cmd. Frederick Forbes who brought her to England, and who died in 185152. There were 16 bridesmaids who wore “dresses were all made of white grenadine; those of the African ladies being trimmed with pink, and those of the English ladies with blue. White Burnous cloaks were also worn by the bridesmaids, and white tulle bonnets, with the exception of the children, who wore the new Exhibition hat, trimmed —two with apple-blossoms and four with forget me-nots.” (Names listed at the end for genealogists.)

The couple resided in Brighton for a while before moving to Sierra Leone, Davies’ homeland.

Ina’s Children

Based on letters that Ina Davies sent to Mrs Schön her attitude towards her husband changed, and she came to appreciate him.53

Together they had three children. The first born in 1863 shortly after moving to Sierra Leone, was a girl. Ina named her, with the Queen’s permission, Victoria.

The Queen became Victoria’s Godmother by proxy, and sent her a beautiful gold cup, with a salver, knife, fork, and of the same metal, as a baptismal present. The cup and salver bore the inscription -” To Victoria Davis, from her godmother Victoria Queen of Great Britain and Ireland”;54 the Queen also paid for her to be educated at Cheltenham Ladies’ College.

Victoria appears to have had an excellent ear for music. Whilst in London she made an acquaintance with Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and provided him with the Yoruba folk song – ‘Oloba Yale mi’ that was included in his Twenty-four Negro Melodies55 – can be found on Spotify. (Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was a prominent black musician by the early 1900s, and who was the director of the Rochester Choral Society between 1902 and 1907 – for more about Coleridge-Taylor see: Samual Coleridge-Taylor, Rochester Choral Authority.)

Ina and James‘ marriage broke down and Ina moved to Madeira for her health. Here on 15th August 1880 she died of tuberculosis at Funchal. Her grave is now finally marked, after 139 years, with a gravestone 56.

Epitaph

Whether Ina had a fortunate life is a matter of context – it was an unfortunate one – but one that perhaps was not as unfortunate as it could have been had she remained with King Gezo. Ina’s life was also exceptionally comfortable compared to many children of her age at this time – many living in slum conditions, with little, if any schooling, poor nutrition and perhaps having to work long hours for pence.

The life that Ina had in England was exceptional for a black person and in no way should it be assumed that other black people experienced such privilege. However, although probably not experiencing material deprivation – but did she have ‘freedom’, and did people, other than Mrs Schön, care about Ina? As Queen Victoria’s protégé she was sent back to Africa as a child whose only connection was with the Forbes. Here she was expected to be prepared for the life of a missionary. When it was clear she was unhappy she was brought back to England and sent to stay with the Schöns at Gillingham. After about six years she was sent to Brighton to be prepared for introduction to society – where she would have been regarded as a curiosity. She was then effectively made to marry an older man who was not of her choosing.

“Aina’s Memory” — The Voice of Sarah Forbes Bonetta (1843–1880) – Created by ChatGPT

(A soft wind moves through an open window. The sound of sea gulls far below. She speaks, slowly, as if to herself.)

⸻

I was born Aina,

in a land of red earth and warm rain,

where the drums carried the names of my mothers and fathers

long before my own voice could speak them.

They told me I came into the world

with the cord of life wound around my neck —

a child who had wrestled with death and won.

For that, they said, I was marked by destiny.

Then came the fire.

The shouting.

The men of Dahomey with their iron and smoke.

My father’s house fell, my people scattered,

and I, the princess of a small world,

became a gift in a foreign king’s court.

He called me a present for another ruler across the sea.

How strange that my life should begin again as an offering.

Captain Forbes took me aboard his ship —

HMS Bonetta, he called it.

The men stared, the waves rose.

He said he would take me to a great Queen who would be my mother now.

He wrote my name in his book:

Sarah Forbes Bonetta.

And so Aina was folded up like a letter

and sealed inside a name not her own.

In England they dressed me in lace,

taught me hymns and handwriting.

They said I was clever —

that I had “a very superior mind for one of my race.”

The Queen smiled at me,

and I loved her as a child loves anyone who sees her kindly.

But always, always, I was her black godchild,

her curious proof of mercy.

They meant no cruelty by it,

but it was a kind of cage made of praise.

When I closed my eyes at night,

I saw the old world —

the market at Abeokuta,

the dust rising from dancers’ feet,

the river where the women sang.

No hymn in England could drown that song.

Years later, I married James Labulo Davies —

an African like me, but also English in speech and schooling.

We were both made of two hearts.

The Queen sent us her blessing,

and when our daughter was born,

I named her Victoria,

so she might belong to both worlds as I did —

and perhaps be torn by them less.

Now, as the air in this place grows thin

and my breath falters like a candle’s flame,

I think of the cord around my neck again —

the one they said I escaped at birth.

Perhaps I never did.

Perhaps it has always been there,

soft and unseen,

a reminder of two hands — one African, one English —

pulling from either side.

Yet I am still here.

Not only Sarah. Not only Aina.

Something between.

A bridge, a wound, a witness.

If the Queen remembers me,

let her remember not a rescued child,

but a woman who carried two empires in her body —

and still called both of them home.

Geoff Ettridge aka Geoff Rambler

7 October 2023 – added to 9 November 2025

Information that may be of assistance to Genealogists

The following info is included as it may help those researching their family tree:

Schön Household – 1851

The 1851 Census, whilst living at Brompton, Gillingham, states that James Schön was aged 47 and his wife, 25; however the 1861 Census lists her as being 46 suggesting she was probably aged 35 in 1851. In 1851 they had three children Harriet (7), James (5) and Emily (1). They had a boarder, named Christian Wilhelm (14) and two servants, Frances Fussel (29) and Ann Milton (16). Elizabeth Catherine Drake appears to have been born in Rochester.) The 1861 Census lists four more children: Sarah (8), Charles (6), Fanny (5) and Herbert (3). Listed as visitors were Sarah F Bonetta (18), Laura Hodsoll (20), Caroline Hodsoll (19), Charles M Hodsoll (19) and James H Darnger (19), The household included a Governess, Anne Norris (28), and two servants, Ann Berry (26) and Charlie M Long (23).

James Frederick Schön died in 1889 and is buried in Grange Rd. Cemetery, Gillingham

Bridesmaids attending Ina’s wedding:

There were sixteen bridesmaids, four of whom, Misses Davies, Decker, Robin, and Pratt, were ladies of colour. The English bridesmaids, six of whom were children, who gave a very pretty effect to the scene, included Misses S. Anuand, Stella Sheppard, Bunbury, Joyce, Sophy Hallam, Balfour, L. Balfour, C. Balfour, Schön, and A. Schön.

Sources

- Sun (London), 3 Jan. 1848

- Maritime Policing and the Pax Britannica: The Royal Navy’s Anti-Slavery Patrol in the Caribbean, 1828-1848. John Beeler.

- Dover Telegraph and Cinque Ports General Advertiser, 5 Oct 1850

- Hampshire Advertiser, 15 Sept 1849

- Dover Telegraph and Cinque Ports General Advertiser, 19 Oct 1850

- Morning Chronicle, 19 Oct 1850

- Dahomey & The Dahomans: The Journals of two Missions to the King of Dahomey. Frederick E Forbes, 1851

- Glasgow Courier, 31 Oct 1850

- Liverpool Evening Express, 7 Oct. 1889

- “At her Majesty’s Request’, Walter Dean Myers. 1937. p67

- Illustrated London News, 23 Aug.1862

- Both names appear in reports.

- http://www.thepostmagazine.co.uk/brightonhistory/african-princess-sarah-forbes-bonetta-1843-1880. Accessed 19 Sept. 2023

- http://www.npg.org.uk/whatson/display/2016/black-chronicles-photographic-portraits-1862-1948. Accessed 22 Sept. 2023

- http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/osborne/history-and-stories/sarah-forbes-bonetta. Accessed 19 Sept. 2023

- Crown & Camera: The Royal Family and Photography. 1842-1910. p113

- https://helenrappaport.com/queen-victoria/sarah-forbes-bonetta. Accessed 19 Sept. 2023.

- South Eastern Gazette, 1 October 1850

- British Army Dispatch, 11 Oct 1850

- South Eastern Gazette, 29 Oct. 1850

- Brighton Gazette, 14 Aug. 1862

- Brighton Gazette, 14 Aug. 1862

- South Eastern Gazette, 9 Oct. 1850. 1851 Census lists Ina (Sarah) as a visitor at Winkfield Place.

- “Sarah Forbes Bonetta – Queen Victoria’s African Princess”. 2018, p38

- “At her Majesty’s Request’, Walter Dean Myers. 1937. p3

- https://helenrappaport.com/queen-victoria/sarah-forbes-bonetta. Accessed 17 Sept 2023.

- en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sara_Forbes_Bonetta. Accessed 22 Sept. 2023. Evidence not cited

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sara_Forbes_Bonetta. Accessed 19 Sept 2023

- “At her Majesty’s Request’, Walter Dean Myers. 1937. p68

- Berkshire Chronicle, 23 Jan. 1858

- Sarah Forbes Bonetta, John Van Der Kiste. 2018

- “At her Majesty’s Request’, Walter Dean Myers. 1937. P71

- Southeastern Gazette, 1 Sept. 1857.

- Maidstone Journal and Kentish Advertiser, 30 Nov. 1858

- Liverpool Albion, 15 May 1848.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Schön. Accessed 17 Sept. 2023

- Patriot, 15 Nov. 1849.

- jeffreygreen.co.uk/261-african-students-in-chatham-kent-in-victorian-times. Accessed 19 Sept. 2023

- Wexford People, 23 Jan. 1858

- Sussex Advertiser, 30 Aug. 1859

- Brighton Gazette, 14 Aug. 1862

- Letter from Ina to Mrs Schön dated March 1861. “At Her Majesty’s Request” Myers 1937. p107.

- 1861 Census

- helenrappaport.com/queen-victoria/sarah-forbes-bonetta. Accessed 19 Sept 2023

- Atlas, 6 Aug. 1862

- jetsettimes.com/inspiration/women-empowerment/what-happened-to-sarah-forbes-bonetta-queen-victorias-goddaughter. Accessed 19 Sept. 2023

- Sun (London) 18 Aug. 1862.

- Freeman’s Journal, 15 August 1862.

- L’ Union, 27 Sept. 1862

- Brighton Gazette. 14 Aug 1862

- Brighton Gazette. 21 Aug 1862

- http://www.messynessychic.com/2017/05/16/the-stolen-african-slave-who-became-queen-victorias-goddaughter. Accessed 22 Sept. 2023

- Letter to Mrs Schön April 1868. “At Her Magesty’s Request”, 1937. p124

- Hampshire Independent, 21 Nov. 1863.

- litcaf.com/victoria-davies/#0. Accessed 22 Sept. 2023

- http://www.historycalroots.com/the-final-resting-place-of-sarah-bonetta-forbes-davies. Accessed 21 Sept. 2023

Comments are closed.